4.2.6 Lab – Working with Text Files in the CLI (Instructor Version)

Instructor Note: Red font color or gray highlights indicate text that appears in the instructor copy only.

Objectives

In this lab, you will become familiar with Linux command line text editors and configuration files.

- Part 1: Graphical Text Editors

- Part 2: Command Line Text Editors

- Part 3: Working with Configuration Files

Required Resources

- CyberOps Workstation virtual machine

Instructions

Part 1: Graphical Text Editors

Before you can work with text files in Linux, you must be familiar with text editors.

Text editors are one of the oldest categories of applications created for computers. Linux, like many other operating systems, has many different text editors, with various features and functions. Some text editors include graphical interfaces, while others are only usable via the command line. Each text editor includes a feature set designed to support a specific work scenario. Some text editors focus on the programmer and include features such as syntax highlighting, bracket matching, find and replace, multi-line Regex support, spell check, and other programming-focused features.

To save space and keep the virtual machine lean, the Cisco CyberOps Workstation VM only includes SciTE as a graphical text editor application. SciTE is a simple, small and fast text editor. It does not have many advanced features, but it fully supports the work done in this course.

Note: The choice of text editor is a personal one. There is no such thing as a best text editor. The best text editor is the one that you feel most comfortable with and works best for you.

Step 1: Open SciTE from the GUI

a. Log on to the CyberOps VM as the user analyst using the password cyberops. The account analyst is used as the example user account throughout this lab.

b. On the top bar, navigate to Applications > CyberOPS > SciTE to launch the SciTE text editor.

c. SciTE is simple but includes a few important features: tabbed environment, syntax highlighting and more. Spend a few minutes with SciTE. In the main work area, type or copy and paste the text below:

“Space, is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mindbogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.”

― Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

d. Click File > Save to save the file. Notice that SciTE attempts to save the file to the current user’s home directory, which is analyst, by default. Name the file txt and click Save.

e. Close SciTE by clicking the X icon on the upper right side of the window and then reopen SciTE.

f. Click File > Open… and search for the newly saved file, space.txt.

Could you immediately find space.txt?

g. Even though SciTE is looking at the correct directory (/home/analyst), space.txt is not displayed. This is because SciTE is looking for known extensions and .txt is not one of them. To display all files, click the dropdown menu at the bottom of the Open File window and select All Files (*).

h. Select txt to open it.

Note: While the Linux file systems do not rely on extensions, some applications such as SciTE may attempt to use them to identify file types.

i. Close space.txt when finished.

Step 2: Open SciTE from the Terminal.

a. Alternatively, you can also open SciTE from the command line. Click the terminal icon located in the Dock at the bottom of the desktop. The terminal emulator opens.

b. Type ls to see the contents of the current directory. Notice txt is listed. This means you do not have to provide path information to open the file.

c. Type scite txt to open SciTE. Note that this will not only launch SciTE in the GUI, but it will also automatically load the space.txt text file that was previously created.

[analyst@secOps ~]$ scite space.txt

d. Notice that while SciTE is open on the foreground, the terminal window used to launch it is still open in the background. In addition, notice that the terminal window used to launch SciTE no longer displays the prompt.

Why is the prompt not shown in the terminal?

e. Close this instance of SciTE by either clicking the X icon as before, or by switching the focus back to the terminal window that launched SciTE and stopping the process. You can stop the process by pressing CTRL+C.

Note: Starting SciTE from the command line is helpful when you want to run SciTE as root. Simply precede scite with the sudo command, sudo scite.

f. Close SciTE and move on to the next section.

Part 2: Command Line Text Editors

While graphical text editors are convenient and easy to use, command line-based text editors are very important in Linux computers. The main benefit of command line-based text editors is that they allow for text file editing from a remote shell on a remote computer.

Consider the following scenario. A user must perform administrative tasks on a Linux computer but is not sitting in front of that computer. Using SSH, the user starts a remote shell to the aforementioned computer. Under the text-based remote shell, the graphical interface may not be available which makes it impossible to rely on graphical text editors. In this type of situation, text-based text editors are crucial.

Note: This is mainly true when connecting to remote, headless servers that lack a GUI interface.

The Cisco CyberOps Workstation VM includes a few command line-based text editors. This course focuses on nano.

Note: Another extremely popular text editor is called vi. While the learning curve for vi is considered steep, vi is a very powerful command line-based text editor. It is included by default in almost all Linux distributions and its original code was first created in 1976. An updated version of vi is named vim which stands for vi-improved. Today most vi users are actually using the updated version, vim.

Due to the lack of graphical support, nano (or GNU nano) can be controlled solely through the keyboard. CTRL+O saves the current file; CTRL+W opens the search menu. GNU nano uses a two-line shortcut bar at the bottom of the screen, where a number of commands for the current context are listed. After nano is open, press CTRL+G for the help screen and a complete list.

a. In the terminal window, type nano space.txt to open the text file created in Part 1.

[analyst@secOps ~]$ nano space.txt

b. nano will launch and automatically load the txt text file. While the text may seem to be truncated or incomplete, it is not. Because the text was created with no return characters and line wrapping is not enabled, by default, nano is displaying one long line of text.

Use the Home and End keyboard keys to quickly navigate to the beginning and to the end of a line, respectively.

What character does nano use to represent that a line continues beyond the boundaries of the screen?

c. As shown on the bottom shortcut lines, CTRL+X can be used to exit nano. nano will ask if you want to save the file before exiting (‘Y’ for Yes, or N for ‘No’). If ‘Y’ is chosen, you will be prompted to press enter to accept the given file name, or change the file name, or provide a file name if it is a new unnamed document.

d. To control nano, you can use CTRL, ALT, ESCAPE or the META keys. The META key is the key on the keyboard with a Windows or Mac logo, depending on your keyboard configuration.

Navigation in nano is very user friendly. Use the arrows to move around the files. Page Up and Page Down can also be used to skip forward or backwards entire pages. Spend some time with nano and its help screen. To enter the help screen, press CTRL+G. Press q to quit the help screen and return to document editing in nano.

Part 3: Working with Configuration Files

In Linux, everything is treated as a file, including the memory, the disks, the monitor output, the files, and the directories. From the operating system standpoint, everything is a file. It should be no surprise that the system itself is configured through files. Known as configuration files, they are usually text files and are used by various applications and services to store adjustments and settings for that specific application or service. Practically everything in Linux relies on configuration files to work. Some services have not one but several configuration files.

Users with proper permission levels use text editors to change the contents of such configuration files. After the changes are made, the file is saved and can be used by the related service or application. Users are able to specify exactly how they want any given application or service to behave. When launched, services and applications check the contents of specific configuration files and adjust their behavior accordingly.

Step 1: Locating Configuration Files

The program author defines the location of configuration for a given program (service or application). Because of that, the documentation should be consulted when assessing the location of the configuration file. Conventionally however, in Linux, configuration files that are used to configure user applications are often placed in the user’s home directory while configuration files used to control system-wide services are placed in the /etc directory. Users always have permission to write to their own home directories and are able to configure the behavior of applications they use.

a. Use the ls command to list all the files in the analyst home directory:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ ls –l total 20 drwxr-xr-x 2 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 22 2018 Desktop drwxr-xr-x 3 analyst analyst 4096 Apr 2 14:44 Downloads drwxr-xr-x 9 analyst analyst 4096 Jul 19 2018 lab.support.files drwxr-xr-x 2 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 21 2018 second_drive -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 255 Apr 17 16:42 space.txt

While a few files are displayed, none of them seem to be configuration files. This is because it is convention to hide home-directory-hosted configuration files by preceding their names with a “.” (dot) character.

b. Use the ls command again but this time add the –a option to also include hidden files in the output:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ ls –la total 144 drwx------ 14 analyst analyst 4096 Apr 17 16:34 . drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Mar 20 2018 .. -rw------- 1 analyst analyst 424 Apr 17 12:52 .bash_history -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 21 Feb 7 2018 .bash_logout -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 57 Feb 7 2018 .bash_profile -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 97 Mar 20 2018 .bashrc -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 141 Feb 7 2018 .bashrc_stock drwxr-xr-x 8 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 25 12:18 .cache drwxr-xr-x 10 analyst analyst 4096 Jul 19 2018 .config drwxr-xr-x 2 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 22 2018 Desktop -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 23 Mar 23 2018 .dmrc drwxr-xr-x 3 analyst analyst 4096 Apr 2 14:44 Downloads drwx------ 3 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 22 2018 .gnupg -rw------- 1 analyst analyst 2520 Mar 24 12:32 .ICEauthority drwxr-xr-x 2 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 24 2018 .idlerc drwxr-xr-x 9 analyst analyst 4096 Jul 19 2018 lab.support.files -rw------- 1 analyst analyst 61 Mar 24 12:36 .lesshst drwxr-xr-x 3 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 22 2018 .local drwx------ 5 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 24 2018 .mozilla drwxr-xr-x 2 analyst analyst 4096 Mar 21 2018 second_drive -rw-r--r-- 1 analyst analyst 255 Apr 17 16:42 space.txt <Some output omitted>

c. Use cat command to display the contents of the .bashrc file. This file is used to configure user-specific terminal behavior and customization.

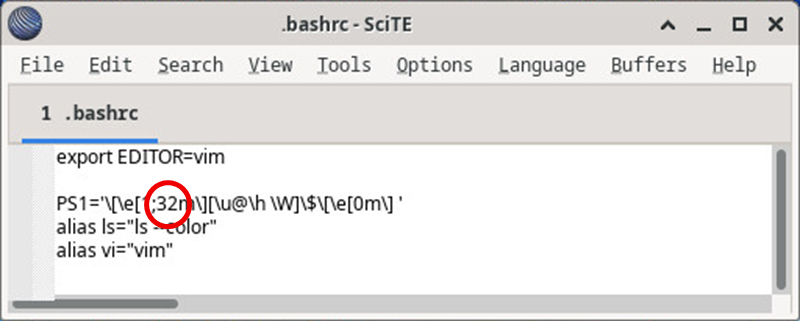

[analyst@secOps ~]$ cat .bashrc export EDITOR=vim PS1='\[\e[1;32m\][\u@\h \W]\$\[\e[0m\] ' alias ls="ls --color" alias vi="vim"

Do not worry too much about the syntax of .bashrc at this point. The important thing to notice is that .bashrc contains configuration for the terminal. For example, the line PS1=’\[\e[1;32m\][\u@\h \W]\$\[\e[0m\] ‘ defines the prompt structure of the prompt displayed by the terminal: [username@hostname current_dir] followed by a dollar sign, all in green. A few other configurations include shortcuts to commands such as ls and vi. In this case, every time the user types ls, the shell automatically converts that to ls –color to display a color-coded output for ls (directories in blue, regular files in grey, executable files in green, etc.)

The specific syntax is out of the scope of this course. What is important is understanding that user configurations are conventionally stored as hidden files in the user’s home directory.

d. While configuration files related to user applications are conventionally placed under the user’s home directory, configuration files relating to system-wide services are place in the /etc directory, by convention. Web services, print services, ftp services, and email services are examples of services that affect the entire system and of which configuration files are stored under /etc. Notice that regular users do not have writing access to /etc. This is important as it restricts the ability to change the system-wide service configuration to the root user only.

Use the ls command to list the contents of the /etc directory:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ ls /etc adjtime host.conf mke2fs.conf rc_maps.cfg apache-ant hostname mkinitcpio.conf request-key.conf apparmor.d hosts mkinitcpio.d request-key.d arch-release ifplugd modprobe.d resolv.conf avahi initcpio modules-load.d resolvconf.conf bash.bash_logout inputrc motd rpc bash.bashrc iproute2 mtab rsyslog.conf binfmt.d iptables nanorc securetty ca-certificates issue netconfig security crypttab java-7-openjdk netctl services dbus-1 java-8-openjdk netsniff-ng shadow default kernel nginx shadow- depmod.d krb5.conf nscd.conf shells dhcpcd.conf ld.so.cache nsswitch.conf skel dhcpcd.duid ld.so.conf ntp.conf ssh dkms ld.so.conf.d openldap ssl drirc libnl openvswitch sudoers elasticsearch libpaper.d os-release sudoers.d environment lightdm pacman.conf sudoers.pacnew ethertypes locale.conf pacman.conf.pacnew sysctl.d filebeat locale.gen pacman.d systemd fonts locale.gen.pacnew pam.d tmpfiles.d fstab localtime pango trusted-key.key gai.conf login.defs papersize udev gemrc logrotate.conf passwd UPower group logrotate.d passwd- vdpau_wrapper.cfg group- logstash pcmcia vimrc group.pacnew lvm pkcs11 webapps grub.d machine-id polkit-1 wgetrc gshadow mail.rc profile X11 gshadow- makepkg.conf profile.d xdg gshadow.pacnew man_db.conf protocols xinetd.d gtk-2.0 mdadm.conf pulse yaourtrc gtk-3.0 mime.types rc_keymaps

e. Use the cat command to display the contents of the bash.bashrc file:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ cat /etc/bash.bashrc

#

# /etc/bash.bashrc

#

# If not running interactively, don't do anything

[[ $- != *i* ]] && return

[[ $DISPLAY ]] && shopt -s checkwinsize

PS1='[\u@\h \W]\$ '

case ${TERM} in

xterm*|rxvt*|Eterm|aterm|kterm|gnome*)

PROMPT_COMMAND=${PROMPT_COMMAND:+$PROMPT_COMMAND; }'printf "\033]0;%s@%s:%s\007" "${USER}" "${HOSTNAME%%.*}" "${PWD/#$HOME/\~}"'

;;

screen)

PROMPT_COMMAND=${PROMPT_COMMAND:+$PROMPT_COMMAND; }'printf "\033_%s@%s:%s\033\\" "${USER}" "${HOSTNAME%%.*}" "${PWD/#$HOME/\~}"'

;;

esac

[ -r /usr/share/bash-completion/bash_completion ] && . /usr/share/bash-completion/bash_completion

[analyst@secOps ~]$

The syntax of bash.bashrc is out of scope of this course. This file defines the default behavior of the shell for all users. If a user wants to customize his/her own shell behavior, the default behavior can be overridden by editing the .bashrc file located in the user’s home directory. Because this is a system-wide configuration, the configuration file is placed under /etc, making it editable only by the root user. Therefore, the user will have to log in as root to modify bash.bashrc.

Why are user application configuration files saved in the user’s home directory and not under /etc with all the other system-wide configuration files?

Step 2: Editing and Saving Configuration files

As mentioned before, configuration files can be edited with text editors.

Let’s edit .bashrc to change the color of the shell prompt from green to red for the analyst user.

a. First, open SciTE by selecting Applications > CyberOPS > SciTE from the tool bar located in the upper portion of the Cisco CyberOPS VM

b. Select File > Open to launch SciTE’s Open File window.

c. Because .bashrc is a hidden file with no extension, SciTE does not display it in the file list. If the Location feature is not visible in the dialog box, Change the type of file shown by selecting All Files (*) from the type drop box, as shown below. All the files in the analyst’s home directory are shown.

d. Select .bashrc and click Open.

e. Locate 32 and replace it with 31. 32 is the color code for green, while 31 represents red.

f. Save the file by selecting File > Save and close SciTE by clicking the X

g. Click the Terminal application icon located on the Dock, at the bottom center of the Cisco CyberOPS VM The prompt should appear in red instead of green.

Did the terminal window which was already open also change color from green to red? Explain.

f. The same change could have been made from the command line with a text editor such as nano. From a new terminal window, type nano .bashrc to launch nano and automatically load the .bashrc file in it:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ nano .bashrc

GNU nano 4.9.2 File: .bashrc

export EDITOR=vim

PS1='\[\e[1;31m\][\u@\h \W]\$\[\e[0m\] '

alias ls="ls --color"

alias vi="vim"

[ Read 5 lines ]

^G Get Help ^O Write Out ^W Where Is ^K Cut Text ^J Justify ^C Cur Pos

^X Exit ^R Read File ^\ Replace ^U Uncut Text^T To Spell ^_ Go To Line

i. Change 31 to 33. 33 is the color code to yellow.

j. Press CTRL+X to save and then press Y to confirm. The text editor nano will also offer you the chance to change the filename. Simply press ENTER to use the same name, .bashrc.

k. The text editor nano will end, and you will be back on the shell prompt. This time reload the bash terminal by entering the command bash in the terminal. The prompt should now appear in yellow instead of red.

Step 2: Editing Configuration Files for Services

System-wide configuration files are not very different from the user-application files. nginx is a lightweight web server that is installed in the Cisco CyberOPS Workstation VM. nginx can be customized by changing its configuration file, which is located in /etc/nginx.

a. First, open nginx’s configuration file in a nano. The configuration file name used here is custom_server.conf. Notice below that the command is preceded by the sudo command. After typing nano include a space and the -l switch to turn on line-numbering.

[analyst@secOps ~]$ sudo nano -l /etc/nginx/custom_server.conf [sudo] password for analyst:

Use the arrow keys to navigate through the file.

GNU nano 4.9.2 /etc/nginx/custom_server.conf

1

2 #user html;

3 worker_processes 1;

4

5 #error_log logs/error.log;

6 #error_log logs/error.log notice;

7 #error_log logs/error.log info;

8

9 #pid logs/nginx.pid;

10

11

12 events {

13 worker_connections 1024;

14 }

15

16

17 http {

18 include mime.types;

19 default_type application/octet-stream;

20

21 #log_format main '$remote_addr - $remote_user [$time_local] "$request" '

22 # '$status $body_bytes_sent "$http_referer" '

23 # '"$http_user_agent" "$http_x_forwarded_for"';

24

25 #access_log logs/access.log main;

26

27 sendfile on;

28 #tcp_nopush on;

29

30 #keepalive_timeout 0;

31 keepalive_timeout 65;

32

33 #gzip on;

34

35 types_hash_max_size 4096;

36 server_names_hash_bucket_size 128;

37

38 server {

39 listen 81;

40 server_name localhost;

41

42 #charset koi8-r;

43

44 #access_log logs/host.access.log main;

45

46 location / {

47 root /usr/share/nginx/html;

48 index index.html index.htm;

49 }

<Some output omitted>

Note: Conventionally, .conf extensions are used to identify configuration files.

b. While the configuration file has many parameters, we will configure only two: the port nginx listens on for incoming connections, and the directory it will serve web pages from, including the index HTML homepage file.

c. Notice that at the bottom of the window, above the nano commands, the line number is highlighted and listed. On line 39, change the port number from 81 to 8080. This will tell nginx to listen to HTTP requests on port TCP 8080.

d. Next, move to line 47 and change the path from /usr/share/nginx/html/ to /usr/share/nginx/html/text_ed_lab/

Note: Be careful not to remove the semi-colon at the end of the line or nginx will throw an error on startup.

e. Press CTRL+X to save the file. Press Y and then ENTER to confirm and use the conf as the filename.

f. Type the command below to execute nginx using the modified configuration file:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ sudo nginx -c custom_server.conf

g. Click the web browser icon on the Dock to launch Firefox.

h. On the address bar, type 0.0.1:8080 to connect to a web server hosted on the local machine on port 8080. A page related to this lab should appear.

i. After successfully opening the nginx homepage, look at the connection message in the terminal window.

What is the error message referring to?

j. To shut down the nginx webserver, press ENTER to get a command prompt and type the following command in the terminal window:

[analyst@secOps ~]$ sudo pkill nginx

k. You can test whether the nginx server is indeed shut down by first clearing the recent history in the web browser, then close and re-open the web browser, then go to the nginx homepage at 127.0.0.1:8080.

Does the web page appear?

Challenge Question: Can you edit the /etc/nginx/custom_configuration.conf file with SciTE? Describe the process below.

Remember, because the file is stored under /etc, you will need root permissions to edit it.

Reflection

Depending on the service, more options may be available for configuration.

Configuration file location, syntax, and available parameters will vary from service to service. Always consult the documentation for information.

Permissions are a very common cause of problems. Make sure you have the correct permissions before trying to edit configuration files.

More often than not, services must be restarted before the changes take effect.