11.0 Introduction

11.0.1 Why Should I Take this Module?

The network infrastructure defines the way in which devices are connected together to achieve end-to-end communications. Just as there are many sizes of networks, there are also many ways to build an infrastructure. However, there are some standard designs that the network industry recommends achieving networks that are available and secure.

This module covers the basic operation of network infrastructures, including wired and wireless networks.

11.0.2 What Will I Learn in this Module?

Module Title: Network Communication Devices

Module Objective: Explain how network devices enable wired and wireless network communication.

| Topic Title | Topic Objective |

|---|---|

| Network Devices | Explain how network devices enable network communication. |

| Wireless Communications | Explain how wireless devices enable network communication. |

11.1 Network Devices

11.1.1 End Devices

The network devices that people are most familiar with are end devices. To distinguish one end device from another, each end device on a network has an address. When an end device initiates communication, it uses the address of the destination end device to specify where to deliver the message.

An end device is either the source or destination of a message transmitted over the network.

Click Play in the figure to see an animation of data flowing through a network.

11.1.2 Video – End Devices

Watch the video to learn more about end devices.

11.1.3 Routers

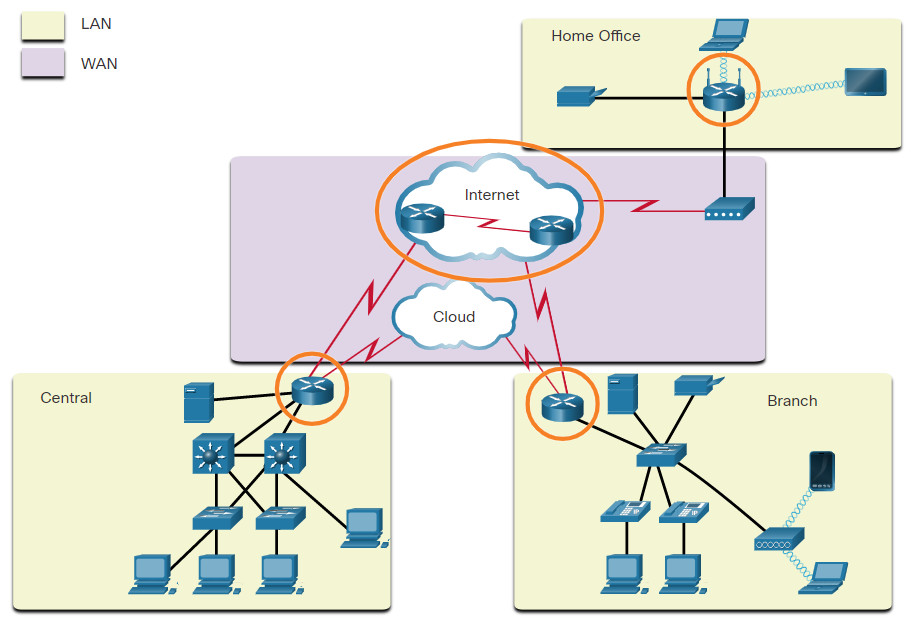

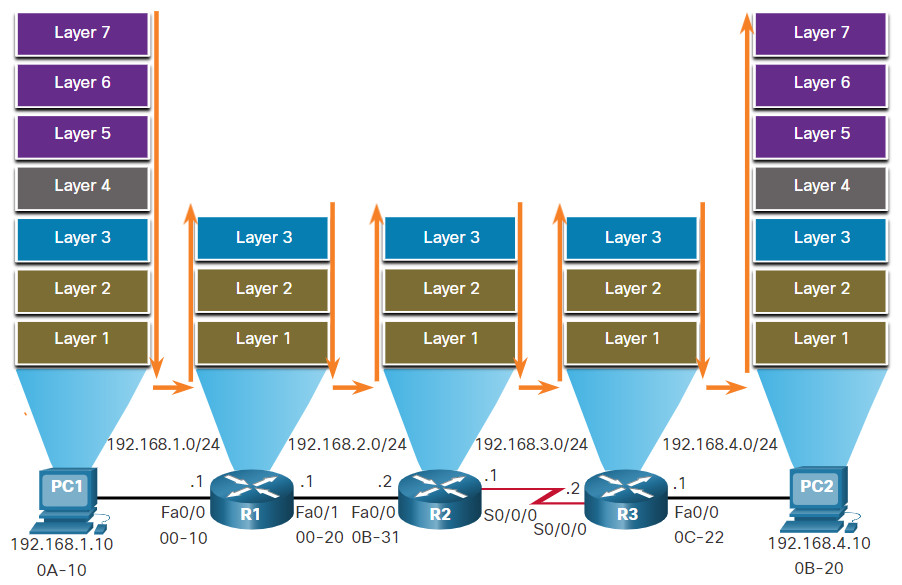

Routers are devices that operate at the OSI network layer (Layer 3). As shown in the figure, routers are used to interconnect remote sites. They use the process of routing to forward data packets between networks. The routing process uses network routing tables, protocols, and algorithms to determine the most efficient path for forwarding an IP packet. Routers gather routing information and update other routers about changes in the network. Routers increase the scalability of networks by segmenting broadcast domains.

Image shows four boxes, one at the top of the graphic labeled Home Office and containing a wireless router, a printer connected by a line representing a wired connection, a wireless tablet, and a wireless laptop. A line connects the wireless router to a cable modem, which connects to the second box labeled WAN, containing a cloud labeled Internet and another cloud labeled Cloud. There are two boxes at the bottom of the graphic, one labeled Central and one labeled Branch. Both boxes contain router icons connected to the Cloud and to the Internet with WAN media shown as red lightning bolts. In the Central box, there are two multilayer switch icons, connected to two LAN switches. There is a server connected directly to the router and four computers connected to the switches. In the box labeled Branch, there are six end devices connected to a switch icon. The six devices are a server, a printer, two IP phones and two computers. Also connected to the LAN switch is a wireless access point. A wireless tablet and a wireless laptop are shown connecting to the wireless access point.

The Router Connection

Routers have two primary functions: path determination and packet forwarding. To perform path determination, each router builds and maintains a routing table which is a database of known networks and how to reach them. The routing table can be built manually and contain static routes or can be built using a dynamic routing protocol.

Packet forwarding is accomplished by using a switching function. Switching is the process used by a router to accept a packet on one interface and forward it out of another interface. A primary responsibility of the switching function is to encapsulate packets in the appropriate data link frame type for the outgoing data link.

Play the animation of routers R1 and R2 receiving a packet from one network and forwarding the packet toward the destination network.

After the router has determined the exit interface using the path determination function, the router must encapsulate the packet into the data link frame of the outgoing interface.

What does a router do with a packet received from one network and destined for another network? The router performs the following three major steps:

- It de-encapsulates the Layer 2 frame header and trailer to expose the Layer 3 packet.

- It examines the destination IP address of the IP packet to find the best path in the routing table.

- If the router finds a path to the destination, it encapsulates the Layer 3 packet into a new Layer 2 frame and forwards that frame out the exit interface.

As shown in the figure, devices have Layer 3 IPv4 addresses, while Ethernet interfaces have Layer 2 data link addresses. The MAC addresses are shortened to simplify the illustration. For example, PC1 is configured with IPv4 address 192.168.1.10 and an example MAC address of 0A-10. As a packet travels from the source device to the final destination device, the Layer 3 IP addresses do not change. This is because the Layer 3 PDU does not change. However, the Layer 2 data link addresses change at every router on the path to the destination, as the packet is de-encapsulated and re-encapsulated in a new Layer 2 frame.

Encapsulating and De-Encapsulating Packets

11.1.5 Packet Forwarding Decision Process

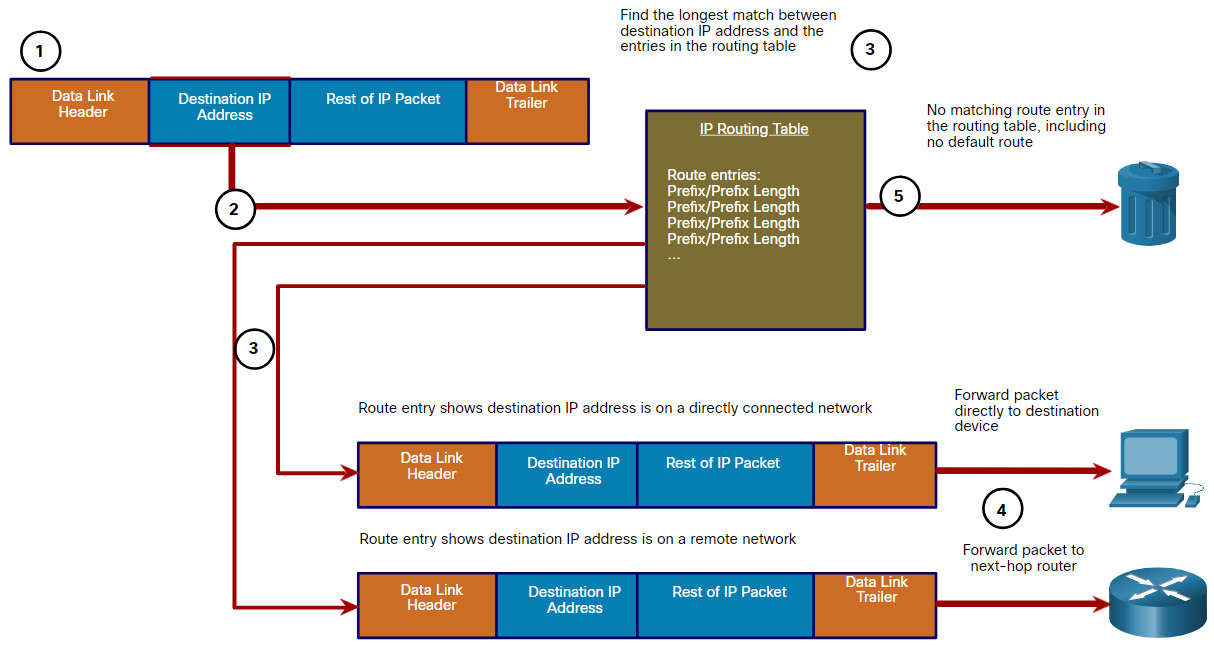

Now that the router has determined the best path for a packet based on the longest match, it must determine how to encapsulate the packet and forward it out the correct egress interface.

The figure explains how a router determines the best path to use to forward a packet.

The following steps describe the packet forwarding process shown in the figure:

- The data link frame with an encapsulated IP packet arrives on the ingress interface.

- The router examines the destination IP address in the packet header and consults its IP routing table.

- The router finds the longest matching prefix in the routing table.

- The router encapsulates the packet in a data link frame and forwards it out the egress interface. The destination could be a device connected to the network or a next-hop router.

- However, if there is no matching route entry the packet is dropped.

Click each button for a description of the three things a router can do with a packet after it has determined the best path.

11.1.6 Routing Information

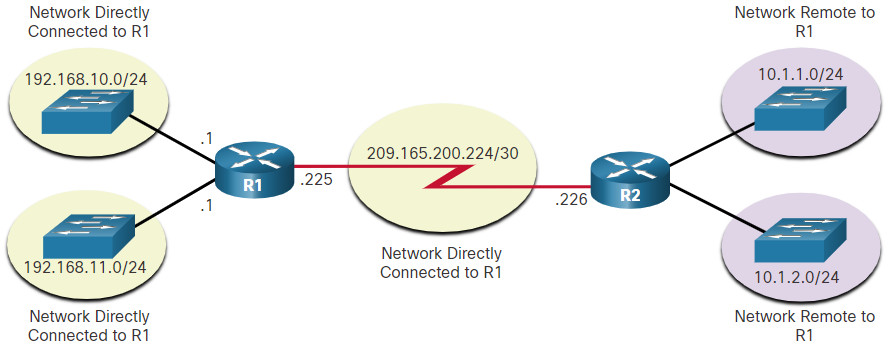

The routing table of a router stores the following information:

- Directly connected routes – These routes come from the active router interfaces. Routers add a directly connected route when an interface is configured with an IP address and is activated.

- Remote routes – These are remote networks connected to other routers. Routes to these networks can either be statically configured or dynamically learned through dynamic routing protocols.

Specifically, a routing table is a data file in RAM that is used to store route information about directly connected and remote networks. The routing table contains network or next hop associations. These associations tell a router that a particular destination can be optimally reached by sending the packet to a specific router that represents the next hop on the way to the final destination. The next hop association can also be the outgoing or exit interface to the next destination.

The figure identifies the directly connected networks and remote networks of router R1.

Directly Connected and Remote Network Routes

The destination network entries in the routing table can be added in several ways:

- Local Route interfaces – These are added when an interface is configured and active. This entry is only displayed in IOS 15 or newer for IPv4 routes, and all IOS releases for IPv6 routes.

- Directly connected interfaces – These are added to the routing table when an interface is configured and active.

- Static routes – These are added when a route is manually configured and the exit interface is active.

- Dynamic routing protocol – This is added when routing protocols that dynamically learn about the network, such as EIGRP or OSPF, are implemented and networks are identified.

Dynamic routing protocols exchange network reachability information between routers and dynamically adapt to network changes. Each routing protocol uses routing algorithms to determine the best paths between different segments in the network, and updates routing tables with these paths.

Dynamic routing protocols have been used in networks since the late 1980s. One of the first routing protocols was RIP. RIPv1 was released in 1988. As networks evolved and became more complex, new routing protocols emerged. The RIP protocol was updated to RIPv2 to accommodate growth in the network environment. However, RIPv2 still does not scale to the larger network implementations of today. To address the needs of larger networks, two advanced routing protocols were developed: Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) and Intermediate System-to-Intermediate System (IS-IS). Cisco developed the Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (IGRP) and Enhanced IGRP (EIGRP), which also scales well in larger network implementations.

Additionally, there was the need to connect different internetworks and provide routing between them. The Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is now used between Internet Service Providers (ISPs). BGP is also used between ISPs and their larger private clients to exchange routing information.

The table classifies the protocols. Routers configured with these protocols will periodically send messages to other routers. As a cybersecurity analyst, you will see these messages in various logs and packet captures.

| Protocol | Interior Gateway Protocols | Exterior Gateway Protocols | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Vector | Link State | Path Vector | |||

| IPv4 | RIPv2 | EIGRP | OSPFv2 | IS-IS | BGP-4 |

| IPv6 | RIPng | EIGRP for IPv6 | OSPFv3 | IS-IS for IPv6 | BGP-MP |

11.1.7 End-to-End Packet Forwarding

The primary responsibility of the packet forwarding function is to encapsulate packets in the appropriate data link frame type for the outgoing interface. For example, the data link frame format for a serial link could be Point-to-Point (PPP) protocol, High-Level Data Link Control (HDLC) protocol, or some other Layer 2 protocol.

Click each button and play the animations of PC1 sending a packet to PC2. Notice how the contents and format of the data link frame change at each hop.

11.1.8 Video – Static and Dynamic Routing

Play the video to learn about static and dynamic routing.

11.1.9 Hubs, Bridges, LAN Switches

The topology icons for hubs, bridges, and LAN switches are shown in the figure.

An Ethernet hub acts as a multiport repeater that receives an incoming electrical signal (data) on a port. It then immediately forwards a regenerated signal out all other ports. Hubs use physical layer processing to forward data. They do not look at the source and destination MAC address of the Ethernet frame. Hubs connect the network into a star topology with the hub as the central connection point. When two or more end devices connected to a hub send data at the same time, an electrical collision takes place, corrupting the signals. All devices connected to a hub belong to the same collision domain. Only one device can transmit traffic at any given time on a collision domain. If a collision does occur, end devices use CSMA/CD logic to avoid transmission until the network is clear of traffic. Due to the low cost and superiority of Ethernet switching, hubs are seldom used today.

Bridges have two interfaces and are connected between hubs to divide the network into multiple collision domains. Each collision domain can have only one sender at a time. Collisions are isolated by the bridge to a single segment and do not impact devices on other segments. Just like a switch, a bridge makes forwarding decisions based on Ethernet MAC addresses. Bridges are seldom used in modern networks.

LAN switches are essentially multiport bridges that connect devices into a star topology. Like bridges, switches segment a LAN into separate collision domains, one for each switch port. A switch makes forwarding decisions based on Ethernet MAC addresses. The figure shows the Cisco series of 2960-X switches that are commonly used to connect end devices on a LAN.

11.1.10 Switching Operation

Switches use MAC addresses to direct network communications through the switch, to the appropriate port, and toward the destination. A switch is made up of integrated circuits and the accompanying software that controls the data paths through the switch. For a switch to know which port to use to transmit a frame, it must first learn which devices exist on each port. As the switch learns the relationship of ports to devices, it builds a table called a MAC address table, or content addressable memory (CAM) table. CAM is a special type of memory used in high-speed searching applications.

LAN switches determine how to handle incoming data frames by maintaining the MAC address table. A switch builds its MAC address table by recording the MAC address of each device that is connected to each of its ports. The switch uses the information in the MAC address table to send frames destined for a specific device out of the port to which the device is connected.

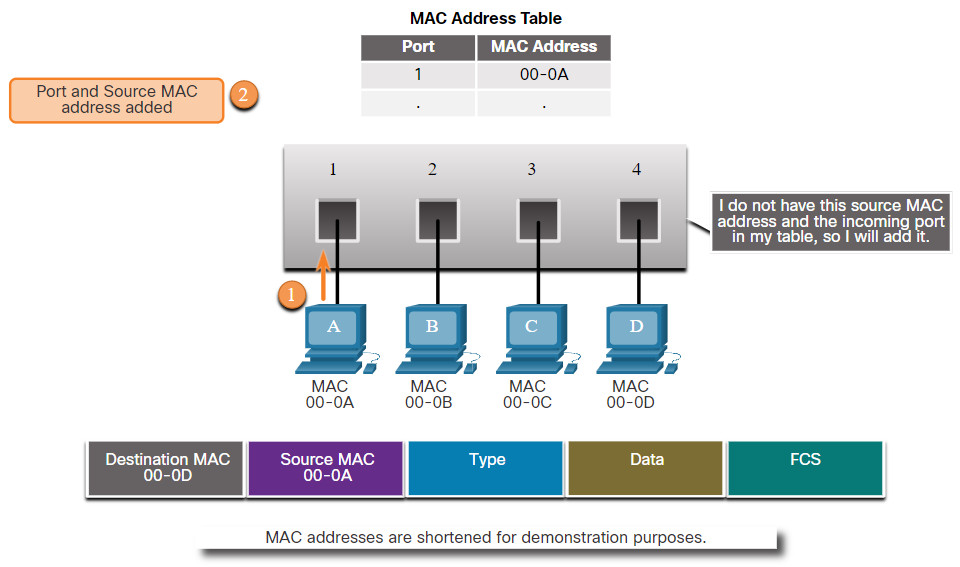

The following two-step process is performed on every Ethernet frame that enters a switch.

1. Learn – Examining the Source MAC Address

Every frame that enters a switch is checked for new MAC address information that may need to be learned. It does this by examining the frame’s source MAC address and the port number where the frame entered the switch. If the source MAC address is not in the table, it is added to the MAC address table along with the incoming port number, as shown in the figure. If the source MAC address does exist in the table, the switch updates the refresh timer for that entry. By default, most Ethernet switches keep an entry in the table for five minutes.

Learn: Examine Source MAC Address

Note: If the source MAC address does exist in the table but on a different port, the switch treats this as a new entry. The entry is replaced using the same MAC address, but with the more current port number.

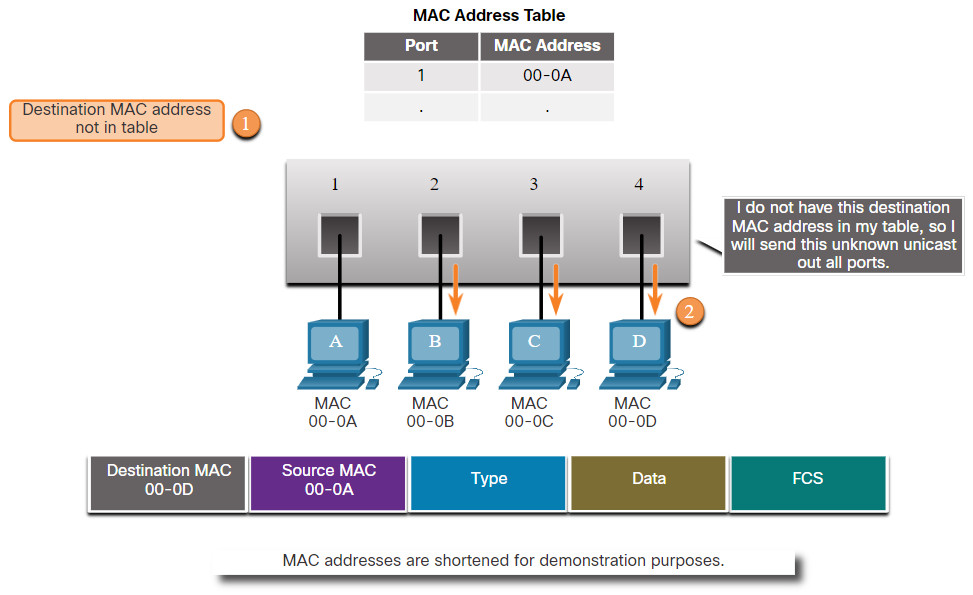

2. Forward – Examining the Destination MAC Address

If the destination MAC address is a unicast address, the switch will look for a match between the destination MAC address of the frame and an entry in its MAC address table. If the destination MAC address is in the table, it will forward the frame out the specified port. If the destination MAC address is not in the table, the switch will forward the frame out all ports except the incoming port, as shown in the figure. This is called an unknown unicast.

Forward: Examining the Destination MAC Address

Note: If the destination MAC address is a broadcast or a multicast, the frame is also flooded out all ports except the incoming port.

11.1.11 Video – MAC Address Tables on Connected Switches

A switch can have multiple MAC addresses associated with a single port. This is common when the switch is connected to another switch. The switch will have a separate MAC address table entry for each frame received with a different source MAC address.

Play the video to see a demonstration of how two connected switches build their MAC address tables.

11.1.12 VLANs

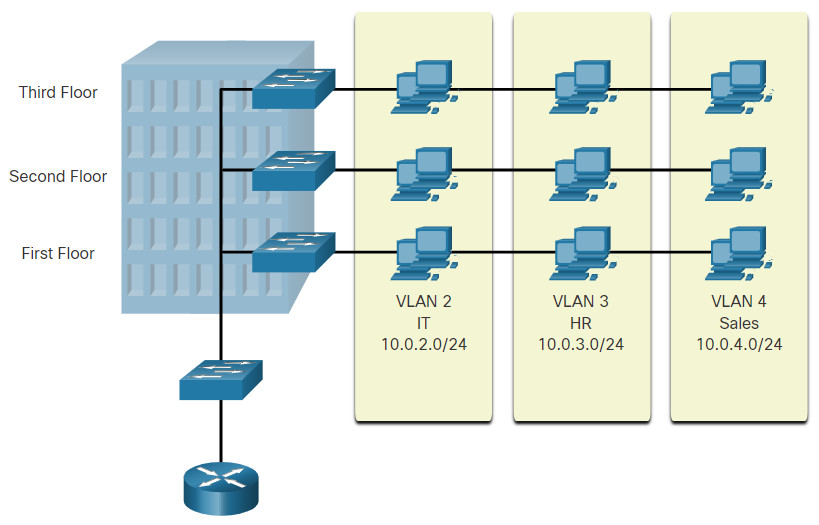

Within a switched internetwork, VLANs provide segmentation and organizational flexibility. VLANs provide a way to group devices within a LAN. A group of devices within a VLAN communicate as if they were connected to the same network segment. VLANs are based on logical connections, instead of physical connections.

VLANs allow an administrator to segment networks based on factors such as function, project team, or application, without regard for the physical location of the user or device, as shown in the figure. Devices within a VLAN act as if they are in their own independent network, even if they share a common infrastructure with other VLANs. Any switch port can belong to a VLAN. Unicast, broadcast, and multicast packets are forwarded and flooded only to end devices within the VLAN where the packets are sourced. Each VLAN is considered a separate logical network. Packets destined for devices that do not belong to the VLAN must be forwarded through a device that supports routing.

A VLAN creates a logical broadcast domain that can span multiple physical LAN segments. VLANs improve network performance by separating large broadcast domains into smaller ones. If a device in one VLAN sends a broadcast Ethernet frame, all devices in the VLAN receive the frame, but devices in other VLANs do not.

VLANs also prevent users on different VLANs from snooping on each other’s traffic. For example, even though HR and Sales are connected to the same switch in the figure, the switch will not forward traffic between the HR and Sales VLANs. This allows a router or another device to use access control lists to permit or deny the traffic. Access lists are discussed in more detail later in the chapter. For now, just remember that VLANs can help limit the amount of data visibility on your LANs.

11.1.13 STP

Network redundancy is a key to maintaining network reliability. Multiple physical links between devices provide redundant paths. The network can then continue to operate when a single link or port has failed. Redundant links can also share the traffic load and increase capacity.

Multiple paths need to be managed so that Layer 2 loops are not created. The best paths are chosen, and an alternate path is immediately available should a primary path fail. The Spanning Tree Protocol is used to maintain one loop-free path in the Layer 2 network, at any time.

Redundancy increases the availability of the network topology by protecting the network from a single point of failure, such as a failed network cable or switch. When physical redundancy is introduced into a design, loops and duplicate frames occur. Loops and duplicate frames have severe consequences for a switched network. STP was developed to address these issues.

STP ensures that there is only one logical path between all destinations on the network by intentionally blocking redundant paths that could cause a loop. A port is considered blocked when user data is prevented from entering or leaving that port. This does not include bridge protocol data unit (BPDU) frames that are used by STP to prevent loops. Blocking the redundant paths is critical to preventing loops on the network. The physical paths still exist to provide redundancy, but these paths are disabled to prevent the loops from occurring. If the path is ever needed to compensate for a network cable or switch failure, STP recalculates the paths and unblocks the necessary ports to allow the redundant path to become active.

11.1.14 Multilayer Switching

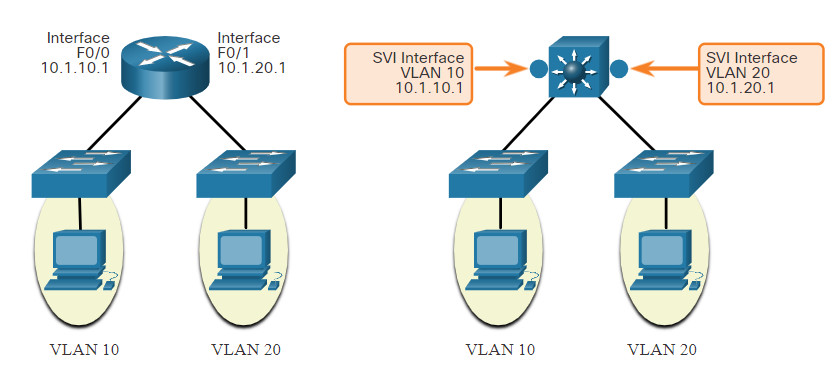

Multilayer switches (also known as Layer 3 switches) not only perform Layer 2 switching, but also forward frames based on Layer 3 and 4 information. All Cisco Catalyst multilayer switches support the following types of Layer 3 interfaces:

- Routed port – A pure Layer 3 interface similar to a physical interface on a Cisco IOS router.

- Switch virtual interface (SVI) – A virtual VLAN interface for inter-VLAN routing. In other words, SVIs are the virtual-routed VLAN interfaces.

Routed Ports

A routed port is a physical port that acts similarly to an interface on a router, as shown in the figure. Unlike an access port, a routed port is not associated with a particular VLAN. A routed port behaves like a regular router interface. Also, because Layer 2 functionality has been removed, Layer 2 protocols, such as STP, do not function on a routed interface. However, some protocols, such as LACP and EtherChannel, do function at Layer 3. Unlike Cisco IOS routers, routed ports on a Cisco IOS switch do not support subinterfaces.

Routed Ports

Switch Virtual Interfaces

An SVI is a virtual interface that is configured within a multilayer switch, as shown in the figure. Unlike the basic Layer 2 switches discussed above, a multilayer switch can have multiple SVIs. An SVI can be created for any VLAN that exists on the switch. An SVI is considered to be virtual because there is no physical port dedicated to the interface. It can perform the same functions for the VLAN as a router interface would, and can be configured in much the same way as a router interface (i.e., IP address, inbound/outbound ACLs, etc.). The SVI for the VLAN provides Layer 3 processing for packets to or from all switch ports associated with that VLAN.

Switch Virtual Interface

11.2 Wireless Communications

11.2.1 Video – Wireless Communications

Watch the video to learn about Wireless LAN (WLAN) operation.

11.2.2 Wireless versus Wired LANs

WLANs use Radio Frequencies (RF) instead of cables at the physical layer and MAC sublayer of the data link layer. WLANs share a similar origin with Ethernet LANs. The IEEE has adopted the 802 LAN/MAN portfolio of computer network architecture standards. The two dominant 802 working groups are 802.3 Ethernet, which defined Ethernet for wired LANs, and 802.11 which defined Ethernet for WLANs. There are important differences between the two.

WLANs also differ from wired LANs as follows:

- WLANs connect clients to the network through a wireless access point (AP) or wireless router, instead of an Ethernet switch.

- WLANs connect mobile devices that are often battery powered, as opposed to plugged-in LAN devices. Wireless NICs tend to reduce the battery life of a mobile device.

- WLANs support hosts that contend for access on the RF media (frequency bands). 802.11 prescribes collision-avoidance (CSMA/CA) instead of collision-detection (CSMA/CD) for media access to proactively avoid collisions within the media.

- WLANs use a different frame format than wired Ethernet LANs. WLANs require additional information in the Layer 2 header of the frame.

- WLANs raise more privacy issues because radio frequencies can reach outside the facility.

The table summarizes the differences between wireless and wired LANs.

| Characteristic | 802.11 Wireless LAN | 802.3 Wired Ethernet LANs |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Layer | radio frequency (RF) | physical cables |

| Media Access | collision avoidance | collision detection |

| Availability | anyone with a wireless NIC in range of an access point | physical cable connection required |

| Signal Interference | yes | minimal |

| Regulation | different regulations by country | IEEE standard dictates |

11.2.3 802.11 Frame Structure

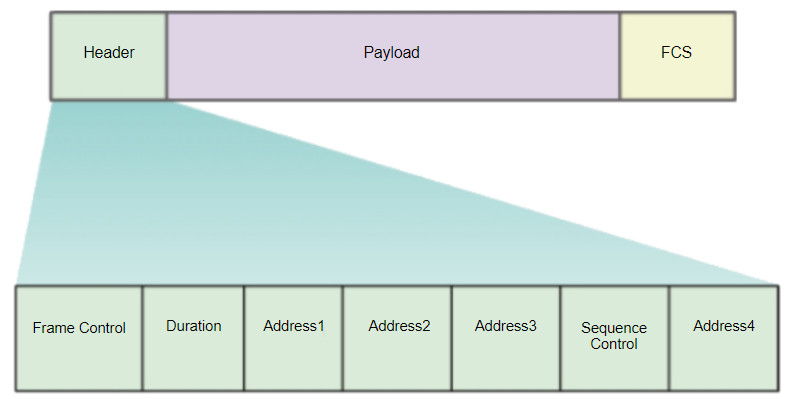

Recall that all Layer 2 frames consist of a header, payload, and Frame Check Sequence (FCS) section. The 802.11 frame format is similar to the Ethernet frame format, except that it contains more fields, as shown in the figure.

All 802.11 wireless frames contain the following fields:

- Frame Control – This identifies the type of wireless frame and contains subfields for protocol version, frame type, address type, power management, and security settings.

- Duration – This is typically used to indicate the remaining duration needed to receive the next frame transmission.

- Address1 – This usually contains the MAC address of the receiving wireless device or AP.

- Address2 – This usually contains the MAC address of the transmitting wireless device or AP.

- Address3 – This sometimes contains the MAC address of the destination, such as the router interface (default gateway) to which the AP is attached.

- Sequence Control – This contains information to control sequencing and fragmented frames.

- Address4 – This usually missing because it is used only in ad hoc mode.

- Payload – This contains the data for transmission.

- FCS – This is used for Layer 2 error control.

11.2.4 CSMA/CA

WLANs are half-duplex, shared media configurations. Half-duplex means that only one client can transmit or receive at any given moment. Shared media means that wireless clients can all transmit and receive on the same radio channel. This creates a problem because a wireless client cannot hear while it is sending, which makes it impossible to detect a collision.

To resolve this problem, WLANs use carrier sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA) as the method to determine how and when to send data on the network. A wireless client does the following:

- Listens to the channel to see if it is idle, which means that is senses no other traffic is currently on the channel. The channel is also called the carrier.

- Sends a ready to send (RTS) message to the AP to request dedicated access to the network.

- Receives a clear to send (CTS) message from the AP granting access to send.

- If the wireless client does not receive a CTS message, it waits a random amount of time before restarting the process.

- After it receives the CTS, it transmits the data.

- All transmissions are acknowledged. If a wireless client does not receive an acknowledgment, it assumes a collision occurred and restarts the process.

11.2.5 Wireless Client and AP Association

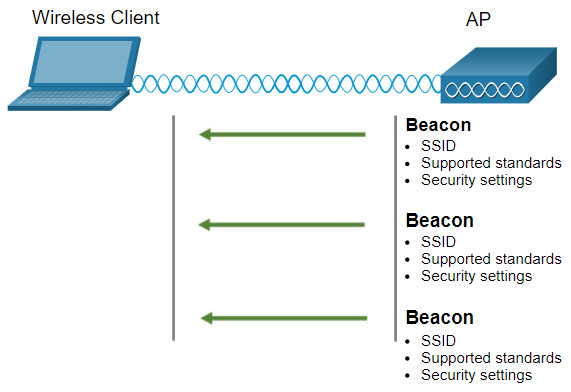

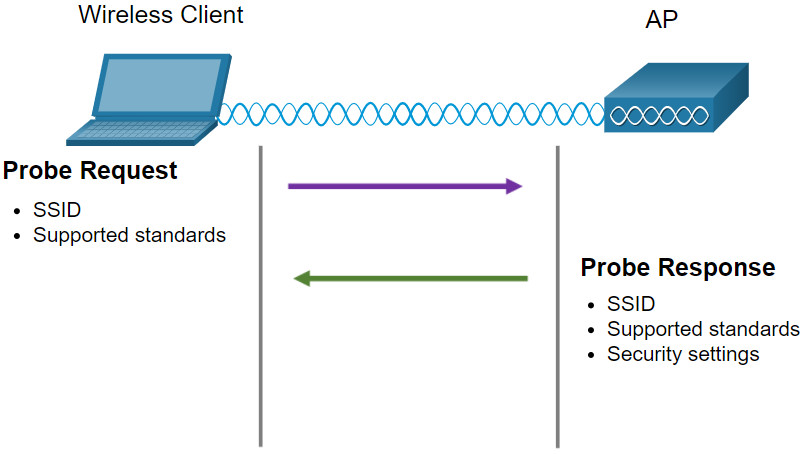

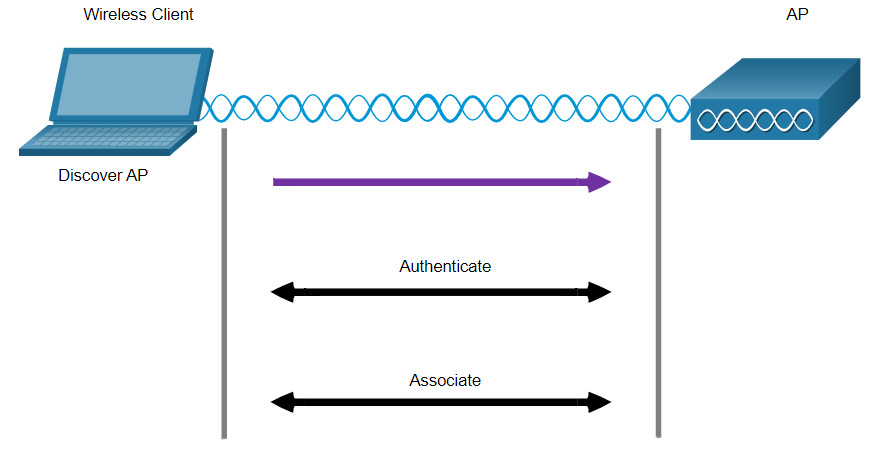

For wireless devices to communicate over a network, they must first associate with an AP or wireless router. An important part of the 802.11 process is discovering a WLAN and subsequently connecting to it. Wireless devices complete the following three stage process, as shown in the figure:

- Discover a wireless AP

- Authenticate with AP

- Associate with AP

In order to have a successful association, a wireless client and an AP must agree on specific parameters. Parameters must then be configured on the AP and subsequently on the client to enable the negotiation of a successful association.

- SSID -The SSID name appears in the list of available wireless networks on a client. In larger organizations that use multiple VLANs to segment traffic, each SSID is mapped to one VLAN. Depending on the network configuration, several APs on a network can share a common SSID.

- Password – This is required from the wireless client to authenticate to the AP.

- Network mode – This refers to the 802.11a/b/g/n/ac/ad WLAN standards. APs and wireless routers can operate in a Mixed mode meaning that they can simultaneously support clients connecting via multiple standards.

- Security mode – This refers to the security parameter settings, such as WEP, WPA, or WPA2. Always enable the highest security level supported.

- Channel settings – This refers to the frequency bands used to transmit wireless data. Wireless routers and APs can scan the radio frequency channels and automatically select an appropriate channel setting. The channel can also be set manually if there is interference with another AP or wireless device.

11.2.6 Passive and Active Discover Mode

Wireless devices must discover and connect to an AP or wireless router. Wireless clients connect to the AP using a scanning (probing) process. This process can be passive or active.

11.2.8 Wireless Devices -AP, LWAP, and WLC

A common wireless data implementation is enabling devices to connect wirelessly via a LAN. In general, a wireless LAN requires wireless access points and clients that have wireless NICs. Home and small business wireless routers integrate the functions of a router, switch, and access point into one device, as shown in the figure. Note that in small networks, the wireless router may be the only AP because only a small area requires wireless coverage. In larger networks, there can be many APs.

All of the control and management functions of the APs on a network can be centralized into a Wireless LAN Controller (WLC). When using a WLC, the APs no longer act autonomously, but instead act as lightweight APs (LWAPs). LWAPs only forward data between the wireless LAN and the WLC. All management functions, such as defining SSIDs and authentication are conducted on the centralized WLC rather than on each individual AP. A major benefit of centralizing the AP management functions in the WLC is simplified configuration and monitoring of numerous access points, among many other benefits.

11.3 Network Communication Devices Summary

11.3.1 What Did I Learn in this Module?

Network Devices

In this module, you learned that end devices that are connected to a LAN connect to other LANs using an internetwork of intermediary devices such as routers and switches.

Routers are network layer (i.e., Layer 3) devices and use the process of routing to forward data packets between networks or subnetworks. Routers provide:

- Path determination – The router builds a routing table containing a list of all known directly connected and remote network routes and how to reach them. The information in the routing table is either configured manually using static routes or discovered dynamically using a dynamic routing protocol (e.g., RIP, OSPF, EIGRP, BGP.) The packet forwarding decision processing is based on the longest match and determines how to encapsulate the packet and forward it out the correct egress interface.

- Packet forwarding services – Incoming packets go through the path determination process to identify the outgoing interface. The router then provides a switching function by encapsulating the outgoing packet in the appropriate data link frame type and forwarding it out the outgoing interface.

Switches segment a LAN into separate collision domains, one for each switch port. A switch makes forwarding decisions based on Ethernet MAC addresses that are contained in the Ethernet frame. The switch uses the frame source address to learn about new MAC addresses, and the destination MAC address to identify the outgoing port to forward the frame. Switches support the creation of VLANs (i.e., logical broadcast domains) to improve network performance and security. For redundancy, switches are often interconnected to provide alternate paths which can cause Layer 2 loop problems. Switches are configured with the Spanning Tree Protocol (STP) to maintain a loop-free Layer 2 path by intentionally blocking redundant paths that could cause a loop.

Multilayer switches (also known as Layer 3 switches) not only perform Layer 2 switching, but also forward frames based on Layer 3 and 4 information. A Cisco Catalyst multilayer switch supports routed ports and switch virtual interfaces (SVIs).

Wireless Communications

Wireless networking devices connect to an Access Point (AP) or Wireless LAN Controller (WLC) suing the 802.11 standard. The 802.11 frame format is similar to the Ethernet frame format, except that it contains additional fields. WLAN devices use carrier sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA) as the method to determine how and when to send data on the network. To connect to the WLAN, wireless devices complete a three-stage process to discover a wireless AP, to authenticate with the AP, and to associate with the AP.

APs can be configured autonomously (individually) or by using a WLC to simplify the configuration and monitoring of numerous access points.