17.0 Introduction

17.0.1 Why Should I Take this Module?

The foundations of the network must be secured, but that is not enough to fully protect your network. The protocols that are used to conduct the day-to-day business of the organization must be protected as well. In addition, protocols and software that provide services over the network can also be the target of threat actors. A cybersecurity analyst must be familiar with the vulnerabilities and threats to the foundations of network communication.

In this module, you will learn how common protocols used in the enterprise work and how they are vulnerable to attack and exploitation.

17.0.2 What Will I Learn in this Module?

Module Title: Attacking What We Do

Module Objective: Explain how common network applications and services are vulnerable to attack.

| Topic Title | Topic Objective |

|---|---|

| IP Services | Explain IP service vulnerabilities |

| Enterprise Services | Explain how network application vulnerabilities enable network attacks |

17.1 IP Services

17.1.1 ARP Vulnerabilities

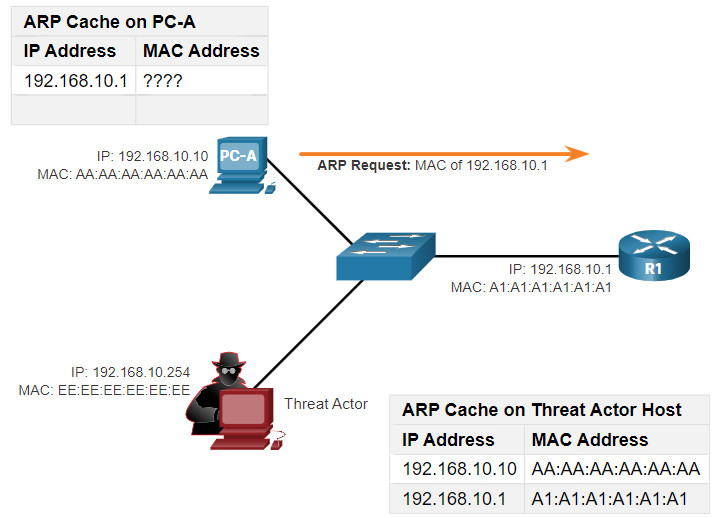

Hosts broadcast an ARP Request to other hosts on the network segment to determine the MAC address of a host with a particular IP address. All hosts on the subnet receive and process the ARP Request. The host with the matching IP address in the ARP Request sends an ARP Reply.

Play in the animation to see the ARP process at work.

Any client can send an unsolicited ARP Reply called a “gratuitous ARP.” This is often done when a device first boots up to inform all other devices on the local network of the new device’s MAC address. When a host sends a gratuitous ARP, other hosts on the subnet store the MAC address and IP address contained in the gratuitous ARP in their ARP tables.

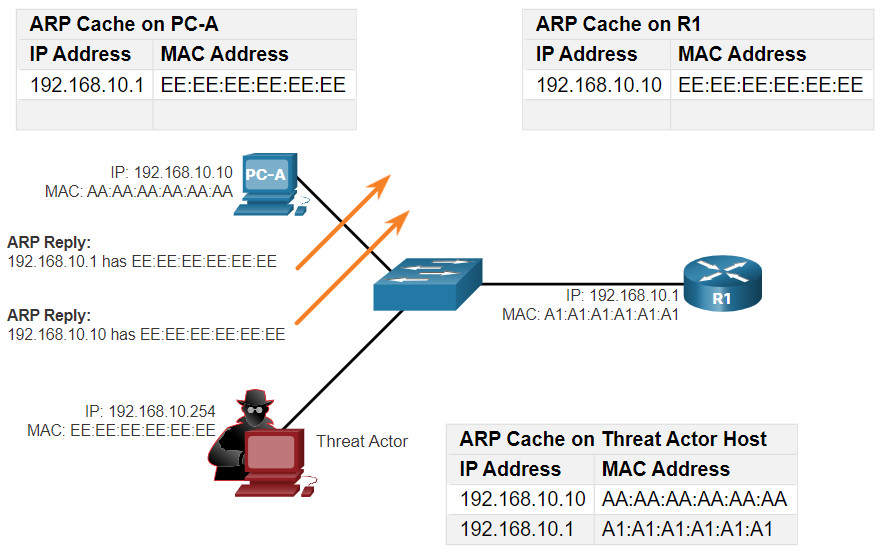

However, this feature of ARP also means that any host can claim to be the owner of any IP/MAC they choose. A threat actor can poison the ARP cache of devices on the local network, creating an MiTM attack to redirect traffic. The goal is to associate the threat actor’s MAC address with the IP address of the default gateway in the ARP caches of hosts on the LAN segment. This positions the threat actor in between the victim and all other systems outside of the local subnet.

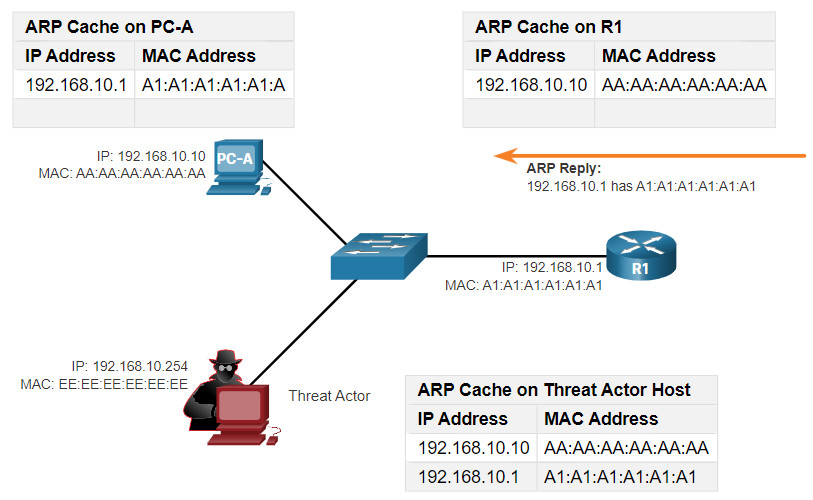

17.1.2 ARP Cache Poisoning

ARP cache poisoning can be used to launch various man-in-the-middle attacks.

Click each button for an illustration and an explanation of the ARP cache poisoning process.

Note: There are many tools available on the internet to create ARP MiTM attacks including dsniff, Cain & Abel, ettercap, Yersinia, and others.

17.1.3 DNS Attacks

The Domain Name Service (DNS) protocol defines an automated service that matches resource names, such as www.cisco.com, with the required numeric network address, such as the IPv4 or IPv6 address. It includes the format for queries, responses, and data and uses resource records (RR) to identify the type of DNS response.

Securing DNS is often overlooked. However, it is crucial to the operation of a network and should be secured accordingly.

DNS attacks include the following:

- DNS open resolver attacks

- DNS stealth attacks

- DNS domain shadowing attacks

- DNS tunneling attacks

DNS Open Resolver Attacks

Many organizations use the services of publicly open DNS servers such as GoogleDNS (8.8.8.8) to provide responses to queries. This type of DNS server is called an open resolver. A DNS open resolver answers queries from clients outside of its administrative domain. DNS open resolvers are vulnerable to multiple malicious activities described in the table.

| DNS Resolver Vulnerabilities | Description |

|---|---|

| DNS cache poisoning attacks | Threat actors send spoofed, falsified record resource (RR) information to a DNS resolver to redirect users from legitimate sites to malicious sites. DNS cache poisoning attacks can all be used to inform the DNS resolver to use a malicious name server that is providing RR information for malicious activities. |

| DNS amplification and reflection attacks | Threat actors use DoS or DDoS attacks on DNS open resolvers to increase the volume of attacks and to hide the true source of an attack. Threat actors send DNS messages to the open resolvers using the IP address of a target host. These attacks are possible because the open resolver will respond to queries from anyone asking a question. |

| DNS resource utilization attacks | A DoS attack that consumes the resources of the DNS open resolvers. This DoS attack consumes all the available resources to negatively affect the operations of the DNS open resolver. The impact of this DoS attack may require the DNS open resolver to be rebooted or services to be stopped and restarted. |

DNS Stealth Attacks

To hide their identity, threat actors also use the DNS stealth techniques described in the table to carry out their attacks.

| DNS Stealth Techniques | Description |

|---|---|

| Fast Flux | Threat actors use this technique to hide their phishing and malware delivery sites behind a quickly-changing network of compromised DNS hosts. The DNS IP addresses are continuously changed within minutes. Botnets often employ Fast Flux techniques to effectively hide malicious servers from being detected. |

| Double IP Flux | Threat actors use this technique to rapidly change the hostname to IP address mappings and to also change the authoritative name server. This increases the difficulty of identifying the source of the attack. |

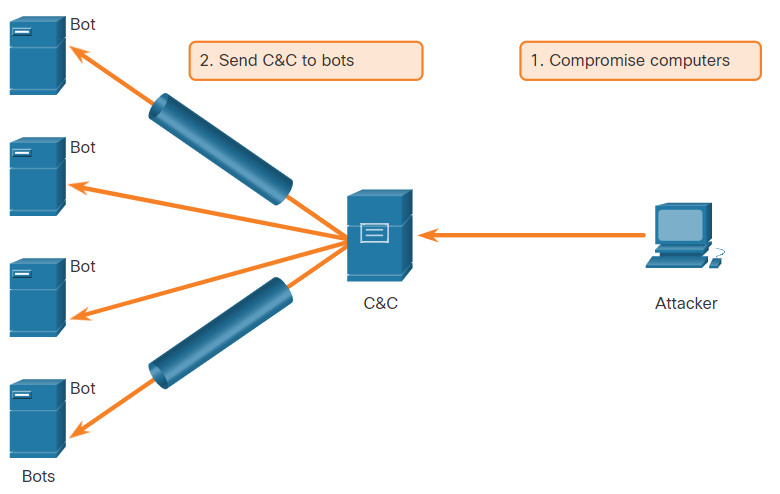

| Domain Generation Algorithms | Threat actors use this technique in malware to randomly generate domain names that can then be used as rendezvous points to their command and control (C&C) servers. |

DNS Domain Shadowing Attacks

Domain shadowing involves the threat actor gathering domain account credentials in order to silently create multiple sub-domains to be used during the attacks. These subdomains typically point to malicious servers without alerting the actual owner of the parent domain.

17.1.4 DNS Tunneling

Botnets have become a popular attack method of threat actors. Most often, botnets are used to spread malware or launch DDoS and phishing attacks.

DNS in the enterprise is sometimes overlooked as a protocol which can be used by botnets. Because of this, when DNS traffic is determined to be part of an incident, the attack is often already over. It is necessary for the cybersecurity analyst to be able to detect when an attacker is using DNS tunneling to steal data, and prevent and contain the attack. To accomplish this, the security analyst must implement a solution that can block the outbound communications from the infected hosts.

Threat actors who use DNS tunneling place non-DNS traffic within DNS traffic. This method often circumvents security solutions. For the threat actor to use DNS tunneling, the different types of DNS records such as TXT, MX, SRV, NULL, A, or CNAME are altered. For example, a TXT record can store the commands that are sent to the infected host bots as DNS replies. A DNS tunneling attack using TXT works like this:

- The data is split into multiple encoded chunks.

- Each chunk is placed into a lower level domain name label of the DNS query.

- Because there is no response from the local or networked DNS for the query, the request is sent to the ISP’s recursive DNS servers.

- The recursive DNS service will forward the query to the attacker’s authoritative name server.

- The process is repeated until all of the queries containing the chunks are sent.

- When the attacker’s authoritative name server receives the DNS queries from the infected devices, it sends responses for each DNS query, which contains the encapsulated, encoded commands.

- The malware on the compromised host recombines the chunks and executes the commands hidden within.

To be able to stop DNS tunneling, a filter that inspects DNS traffic must be used. Pay particular attention to DNS queries that are longer than average, or those that have a suspicious domain name. Also, DNS security solutions, such as Cisco Umbrella (formerly Cisco OpenDNS), block much of the DNS tunneling traffic by identifying suspicious domains. Domains associated with Dynamic DNS services should be considered highly suspect.

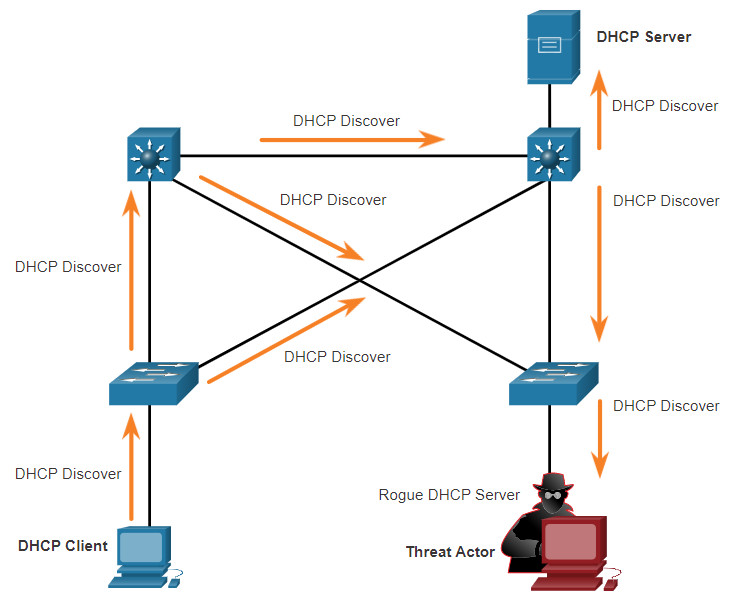

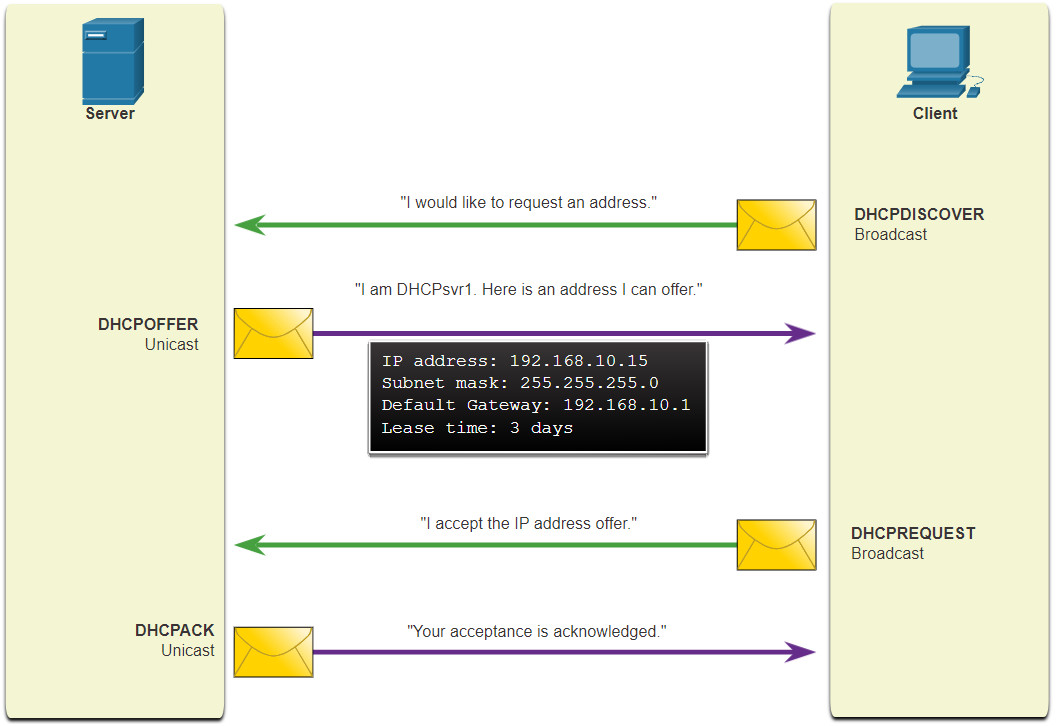

17.1.5 DHCP

DHCP servers dynamically provide IP configuration information to clients. The figure shows the typical sequence of a DHCP message exchange between client and server.

Normal DHCP Operation

In the figure, a client broadcasts a DHCP discover message. The DHCP server responds with a unicast offer that includes addressing information the client can use. The client broadcasts a DHCP request to tell the server that the client accepts the offer. The server responds with a unicast acknowledgment accepting the request.

17.1.6 DHCP Attacks

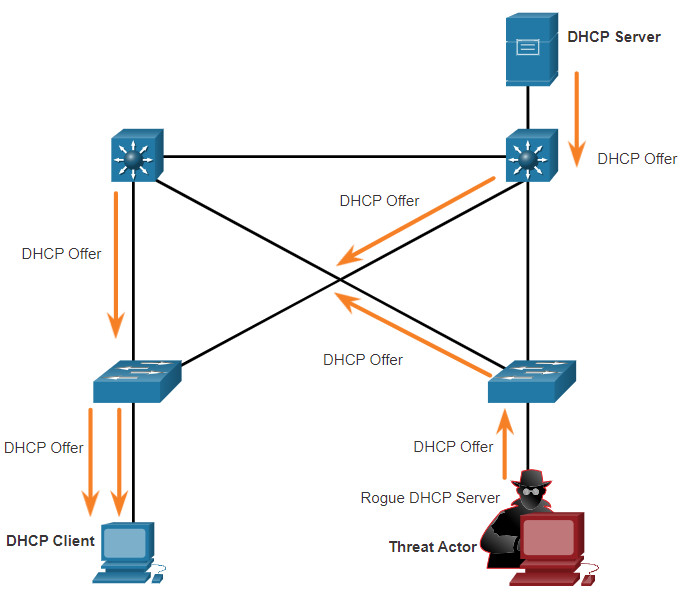

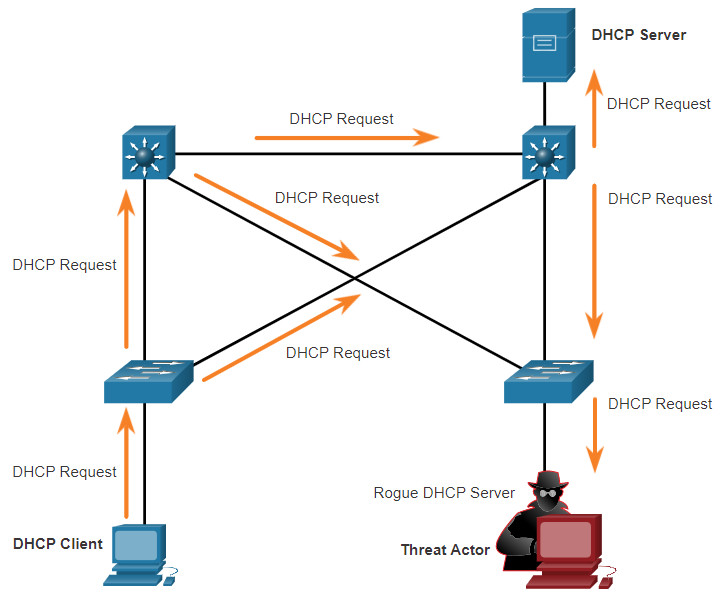

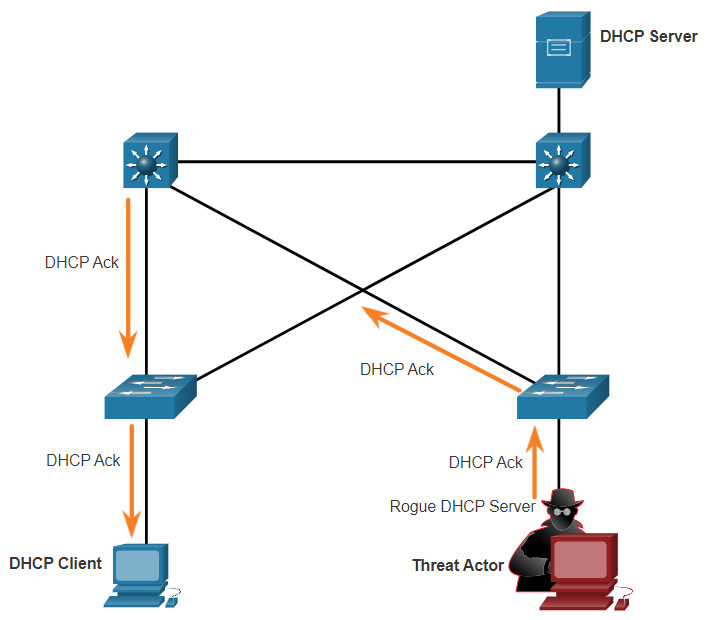

DHCP Spoofing Attack

A DHCP spoofing attack occurs when a rogue DHCP server is connected to the network and provides false IP configuration parameters to legitimate clients. A rogue server can provide a variety of misleading information:

- Wrong default gateway – Threat actor provides an invalid gateway, or the IP address of its host to create a MiTM attack. This may go entirely undetected as the intruder intercepts the data flow through the network.

- Wrong DNS server – Threat actor provides an incorrect DNS server address pointing the user to a malicious website.

- Wrong IP address – Threat actor provides an invalid IP address, invalid default gateway IP address, or both. The threat actor then creates a DoS attack on the DHCP client.

Assume a threat actor has successfully connected a rogue DHCP server to a switch port on the same subnet as the target clients. The goal of the rogue server is to provide clients with false IP configuration information.

Click each button for an illustration and explanation of the steps in a DHCP spoofing attack.

17.1.7 Lab – Exploring DNS Traffic

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

- Capture DNS Traffic

- Explore DNS Query Traffic

- Explore DNS Response Traffic

17.1.7 Lab – Exploring DNS Traffic

17.2 Enterprise Services

17.2.1 HTTP and HTTPS

Internet browsers are used by almost everyone. Blocking web browsing completely is not an option because businesses need access to the web, without undermining web security.

To investigate web-based attacks, security analysts must have a good understanding of how a standard web-based attack works. These are the common stages of a typical web attack:

- The victim unknowingly visits a web page that has been compromised by malware.

- The compromised web page redirects the user, often through many compromised servers, to a site containing malicious code.

- The user visits this site with malicious code and their computer becomes infected. This is known as a drive by download. When the user visits the site, an exploit kit scans the software running on the victim’s computer including the OS, Java, or Flash player looking for an exploit in the software. The exploit kit is often a PHP script and provides the attacker with a management console to manage the attack.

- After identifying a vulnerable software package running on the victim’s computer, the exploit kit contacts the exploit kit server to download code that can use the vulnerability to run malicious code on the victim’s computer.

- After the victim’s computer has been compromised, it connects to the malware server and downloads a payload. This could be malware, or a file download service that downloads other malware.

- The final malware package is run on the victim’s computer.

Independent of the type of attack being used, the main goal of the threat actor is to ensure the victim’s web browser ends up on the threat actor’s web page, which then serves out the malicious exploit to the victim.

Some malicious sites take advantage of vulnerable plugins or browser vulnerabilities to compromise the client’s system. Larger networks rely on IDSs to scan downloaded files for malware. If detected, the IDS issues alerts and records the event to log files for later analysis.

Server connection logs can often reveal information about the type of scan or attack. The different types of connection status codes are listed here:

- Informational 1xx – This is a provisional response, consisting only of the Status-Line and optional headers. It is terminated by an empty line. There are no required headers for this class of status code. Servers MUST NOT send a 1xx response to an HTTP/1.0 client except under experimental conditions.

- Successful 2xx – The client’s request was successfully received, understood, and accepted.

- Redirection 3xx – Further action must be taken by the user agent to fulfill the request. A client SHOULD detect infinite redirection loops, because these loops generate network traffic for each redirection.

- Client Error 4xx – For cases in which the client seems to have erred. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server SHOULD include an entity containing an explanation of the situation, and if it is temporary. User agents SHOULD display any included entity to the user.

- Server Error 5xx – For cases where the server is aware that it has erred, or it cannot perform the request. Except when responding to a HEAD request, the server SHOULD include an entity containing an explanation of the error situation, and if it is temporary. User agents SHOULD display any included entity to the user.

To defend against web-based attacks, the following countermeasures should be used:

- Always update the OS and browsers with current patches and updates.

- Use a web proxy like Cisco Cloud Web Security or Cisco Web Security Appliance to block malicious sites.

- Use the best security practices from the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) when developing web applications.

- Educate end users by showing them how to avoid web-based attacks.

The OWASP Top 10 Web Application Security Risks is designed to help organizations create secure web applications. It is a useful list of potential vulnerabilities that are commonly exploited by threat actors.

17.2.2 Common HTTP Exploits

Malicious iFrames

Threat actors often make use of malicious inline frames (iFrames). An iFrame is an HTML element that allows the browser to load another web page from another source. iFrame attacks have become very common, as they are often used to insert advertisements from other sources into the page. Threat actors compromise a webserver and modify web pages by adding HTML for the malicious iFrame. The HTML links to the threat actor’s webserver. In some instances, the iFrame page that is loaded consists of only a few pixels. This makes it very hard for the user to see. Because the iFrame is run in the page, it can be used to deliver a malicious exploit, such as spam advertising, an exploit kit, and other malware.

These are some of the ways to prevent or reduce malicious iFrames:

- Use a web proxy to block malicious sites.

- Because attackers often change the source HTML of the iFrame in a compromised web site, make sure web developers do not use iFrames. This will isolate any content from third-party web sites and make modified pages easier to find.

- Use a service such as Cisco Umbrella to prevent users from navigating to web sites that are known to be malicious.

- Make sure the end user understands what an iFrame is. Threat actors often use this method in web-based attacks.

HTTP 302 Cushioning

Another type of HTTP attack is the HTTP 302 cushioning attack. Threat actors use the 302 Found HTTP response status code to direct the user’s web browser to a new location. Threat actors often use legitimate HTTP functions such as HTTP redirects to carry out their attacks. HTTP allows servers to redirect a client’s HTTP request to a different server. HTTP redirection is used, for example, when web content has moved to a different URL or domain name. This allows old URLs and bookmarks to continue to function. Therefore, security analysts should understand how a function such as HTTP redirection works and how it can be used during attacks.

When the response from the server is a 302 Found status, it also provides the URL in the location field. The browser believes that the new location is the URL provided in the header. The browser is invited to request this new URL. This redirect function can be used multiple times until the browser finally lands on the page that contains the exploit. The redirects may be difficult to detect due to the fact that legitimate redirects frequently occur on the network.

These are some ways to prevent or reduce HTTP 302 cushioning attacks:

- Use a web proxy to block malicious sites.

- Use a service such as Cisco Umbrella to prevent users from navigating to web sites that are known to be malicious.

- Make sure the end user understands how the browser is redirected through a series of HTTP 302 redirections.

Domain Shadowing

When a threat actor wishes to create a domain shadowing attack, the threat actor must first compromise a domain. Then, the threat actor must create multiple subdomains of that domain to be used for the attacks. Hijacked domain registration logins are then used to create the many subdomains needed. After these subdomains have been created, attackers can use them as they wish, even if they are found out to be malicious domains. They can simply make more from the parent domain. The following sequence is typically used by threat actors:

- A website becomes compromised.

- HTTP 302 cushioning is used to send the browser to malicious websites.

- Domain shadowing is used to direct the browser to a compromised server.

- An exploit kit landing page is accessed.

- Malware downloads from the exploit kit landing page.

These are some ways to prevent or reduce domain shadowing attacks:

- Secure all domain owner accounts. Use strong passwords and use two-factor authentication to secure these powerful accounts.

- Use a web proxy to block malicious sites.

- Use a service such as Cisco Umbrella to prevent users from navigating to web sites that are known to be malicious.

- Make sure that domain owners validate their registration accounts and look for any subdomains that they have not authorized.

17.2.3 Email

Over the past 25 years, email has evolved from a tool used primarily by technical and research professionals to become the backbone of corporate communications. Each day, more than 100 billion corporate email messages are exchanged. As the level of use rises, security becomes a greater priority. The way that users access email today also increases the opportunity for the threat of malware to be introduced. It used to be that corporate users accessed text-based email from a corporate server. The corporate server was on a workstation that was protected by the company’s firewall. Today, HTML messages are accessed from many different devices that are often not protected by the company’s firewall. HTML allows more attacks because of the amount of access that can sometimes bypass different security layers.

The following are examples of email threats:

- Attachment-based attacks – Threat actors embed malicious content in business files such as an email from the IT department. Legitimate users open malicious content. Malware is used in broad attacks often targeting a specific business vertical to seem legitimate, enticing users working in that vertical to open attachments, or click embedded links.

- Email spoofing – Threat actors create email messages with a forged sender address that is meant to fool the recipient into providing money or sensitive information. For example, a bank sends you an email asking you to update your credentials. When this email displays the identical bank logo as mail you have previously opened that was legitimate, it has a higher chance of being opened, having attachments opened and links clicked. The spoofed email may even ask you to verify your credentials so that the bank is assured that you are you, exposing your login information.

- Spam email – Threat actors send unsolicited email containing advertisements or malicious files. This type of email is sent most often to solicit a response, telling the threat actor that the email is valid and a user has opened the spam.

- Open mail relay server – Threat actors take advantage of enterprise servers that are misconfigured as open mail relays to send large volumes of spam or malware to unsuspecting users. The open mail relay is an SMTP server that allows anybody on the internet to send mail. Because anyone can use the server, they are vulnerable to spammers and worms. Very large volumes of spam can be sent by using an open mail relay. It is important that corporate email servers are never set up as an open relay. This will considerably reduce the amount of unsolicited emails.

- Homoglyphs – Threat actors can use text characters that are very similar or even identical to legitimate text characters. For example, it can be difficult to distinguish between an O (upper case letter O) and a 0 (number zero) or a l (lower case “L”) and a 1 (number one). These can be used in phishing emails to make them look very convincing. In DNS, these characters are very different from the real thing. When the DNS record is searched, a completely different URL is found when the link with the homoglyph is used in the search.

Just like any other service that is listening to a port for incoming connections, SMTP servers also may have vulnerabilities. Always keep SMTP software up to date with security and software patches and updates. To further prevent threat actors from completing their task of fooling the end user, implement countermeasures. Use a security appliance specific to email such as the Cisco Email Security Appliance. This will help to detect and block many known types of threats such as phishing, spam, and malware. Also, educate the end user. When attacks make it by the security measures in place, and they will sometimes, the end user is the last line of defense. Teach them how to recognize spam, phishing attempts, suspicious links and URLs, homoglyphs, and to never open suspicious attachments.

17.2.4 Web-Exposed Databases

Web applications commonly connect to a relational database to access data. Because relational databases often contain sensitive data, databases are a frequent target for attacks.

Code Injection

Attackers are able to execute commands on a web server’s OS through a web application that is vulnerable. This might occur if the web application provides input fields to the attacker for entering malicious data. The attacker’s commands are executed through the web application and have the same permissions as the web application. This type of attack is used because often there is insufficient validation of input. An example is when a threat actor injects PHP code into an insecure input field on server page.

SQL Injection

SQL is the language used to query a relational database. Threat actors use SQL injections to breach the relational database, create malicious SQL queries, and obtain sensitive data from the relational database.

One of the most common database attacks is the SQL injection attack. The SQL injection attack consists of inserting a SQL query via the input data from the client to the application. A successful SQL injection exploit can read sensitive data from the database, modify database data, execute administration operations on the database, and sometimes, issue commands to the operating system.

Unless an application uses strict input data validation, it will be vulnerable to the SQL injection attack. If an application accepts and processes user-supplied data without any input data validation, a threat actor could submit a maliciously crafted input string to trigger the SQL injection attack.

Security analysts should be able to recognize suspicious SQL queries in order to detect if the relational database has been subjected to SQL injection attacks. They need to be able to determine which user ID was used by the threat actor to log in, then identify any information or further access the threat actor could have leveraged after a successful login.

17.2.5 Client-side Scripting

Cross-Site Scripting

Not all attacks are initiated from the server side. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) is where web pages that are executed on the client-side, within their own web browser, are injected with malicious scripts. These scripts can be used by Visual Basic, JavaScript, and others to access a computer, collect sensitive information, or deploy more attacks and spread malware. As with SQL injection, this is often due to the attacker posting content to a trusted website with a lack of input validation. Future visitors to the trusted web site will be exposed to the content provided by the attacker.

These are the two main types of XSS:

- Stored (persistent) – This is permanently stored on the infected server and is received by all visitors to the infected page.

- Reflected (non-persistent) – This only requires that the malicious script is located in a link and visitors must click the infected link to become infected.

These are some ways to prevent or reduce XSS attacks:

- Be sure that web application developers are aware of XSS vulnerabilities and how to avoid them.

- Use an IPS implementation to detect and prevent malicious scripts.

- Use a web proxy to block malicious sites.

- Use a service such as Cisco Umbrella to prevent users from navigating to web sites that are known to be malicious.

- As with all other security measures, be sure to educate end users. Teach them to identify phishing attacks and notify infosec personnel when they are suspicious of anything security-related.

17.2.6 Lab – Attacking a MySQL Database

In this lab, you will view a PCAP file from a previous attack against a SQL database.

17.2.6 Lab – Attacking a mySQL Database

17.2.7 Lab – Reading Server Logs

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

- Reading Log Files with cat, more, and less

- Log Files and Syslog

- Log Files and journalctl

17.2.7 Lab – Reading Server Logs

17.3 Attacking What We Do Summary

17.3.1 What Did I Learn in this Module?

IP Services

Hosts broadcast an ARP Request to other hosts on the network segment to determine the MAC address of a host with a particular IP address. Any client can send an unsolicited ARP Reply called a “gratuitous ARP.” This feature of ARP also means that any host can claim to be the owner of any IP/MAC they choose. A threat actor can poison the ARP cache of devices on the local network, creating an MiTM attack to redirect traffic.

The Domain Name Service (DNS) protocol defines an automated service that matches resource names with the required numeric IP host address. It includes the message format for queries, responses, and data. It uses resource records (RR) to identify the type of DNS response. DNS is crucial to the operation of a network and should be secured accordingly. Many organizations use the services of publicly open DNS servers to provide responses to queries. DNS open resolvers are vulnerable to multiple malicious activities, including DNS cache poisoning, in which falsified records are provided to the open resolver. DNS amplification and reflection attacks are another type of attack in which the benign nature of the DNS protocol is exploited to cause DoS/DDoS attacks. In DNS resource utilization attacks, a DoS attack is launched against the DNS server itself. Threat actors often hide using DNS stealth techniques such as Fast Flux, in which malicious servers will rapidly change their IP address. Threat actors as use Double IP Flux, in which threat actors will rapidly change both their domain name to IP mapping and their authoritative name server. Threat actors may also use domain shadowing to hide the source of their attacks by gathering domain account credentials in order to silently create multiple sub-domains to be used during attacks. DNS in the enterprise is sometimes overlooked as a protocol which can be used by botnets. Threat actors who use DNS tunneling place non-DNS traffic within DNS traffic. This method often circumvents security solutions. To be able to stop DNS tunneling, a filter that inspects DNS traffic must be used. Dynamic DNS servers are popular with threat actors and traffic that uses dynamic DNS should be a special concern of the cybersecurity analyst.

DHCP uses a simple exchange of broadcast and unicast messages to provide hosts with addressing information. A DHCP spoofing attack occurs when a rogue DHCP server is connected to the network and provides false IP configuration parameters to legitimate clients. The rogue server might provide incorrect default gateway information, DNS server information, or IP addressing information.

Enterprise Services

World Wide Web browsers are used by almost everyone. Blocking web browsing completely is not an option because businesses need access to the web. Cybersecurity analysts must have a good understanding of how a standard web-based attack works. The common stages of a typical web attack include the victim unknowingly visiting a web page that has been compromised by malware. The compromised web page redirects the user to a site that hosts malicious code. The browser is made to visit this site and malicious code infects their computer. This is known as a drive-by download. Regardless of the type of attack being used, the main goal of the threat actor is to ensure the victim’s web browser ends up on the threat actor’s web page, which then serves the malicious exploit to the victim. Some malicious sites take advantage of vulnerable plugins or browser vulnerabilities to compromise the client’s system. Larger networks rely on IDSs to scan downloaded files for malware. If detected, the IDS issues alerts and records the event to log files for later analysis. Server connection logs can often reveal information about the type of scan or attack. The different groups of connection status codes include Informational 1xx, Successful 2xx, Redirection 3xx, Client Error 4xx, and Server Error 5xx. To defend against web-based attacks, countermeasures that should be used include always updating the OS and browsers with current patches and updates, using a web proxy to block malicious sites, using the best security practices from the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) when developing web applications, and educating end users by showing them how to avoid web-based attacks.

There are a number of attacks that use email to carry malware payloads or to phish for personal information. SMTP servers can also have vulnerabilities and should be kept up to date with patches. Email security appliances can detect and block many types of known email threats including phishing, spam, and malware.

Web applications commonly connect to databases. Because these databases can contain sensitive information, they are a frequent target of attacks. Code injection and SQL injection attacks exploit insufficiently validated input fields to send commands to databases or other applications in order to gain access to private information. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks occur when browsers execute malicious scripts on the client and provide threat actors with access to sensitive information on the local host.

The OWASP Top 10 Web Application Security Risks is designed to help organizations create secure web applications. It is a useful list of potential vulnerabilities that are commonly exploited by threat actors.