26.0 Introduction

26.0.1 Why Should I Take this Module?

A critical skill for a Cybersecurity Analyst is the ability to evaluate alerts and decide what to do with them. In this module, you will learn where alerts come from, common workflows associated with alerts, and standard methods for evaluating and classifying alerts.

26.0.2 What Will I Learn in this Module?

Module Title: Evaluating Alerts

Module Objective: Explain the process of evaluating alerts

| Topic Title | Topic Objective |

|---|---|

| Source of Alerts | Identify the structure of alerts. |

| Overview of Alert Evaluation | Explain how alerts are classified |

26.1 Sources of Alerts

26.1.1 Security Onion

Security Onion is an open-source suite of Network Security Monitoring (NSM) tools that run on an Ubuntu Linux distribution. Security Onion tools provide three core functions for the cybersecurity analyst: full packet capture and data types, network-based and host-based intrusion detection systems, and alert analyst tools. Security Onion can be installed as a standalone installation or as a sensor and server platform. Some components of Security Onion are owned and maintained by corporations, such as Cisco and Riverbend Technologies, but are made available as open source.

For more information, and to obtain Security Onion, search the internet for the Security Onion website.

Note: In some resources, you may see Security Onion abbreviated as SO. In this course, we will use Security Onion.

26.1.2 Detection Tools for Collecting Alert Data

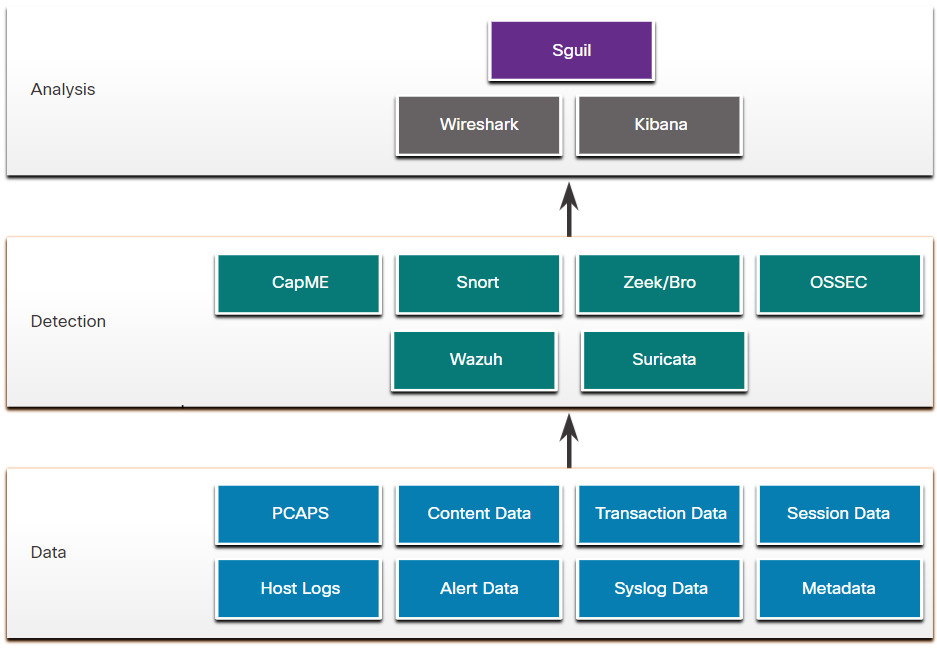

Security Onion contains many components. It is an integrated environment which is designed to simplify the deployment of a comprehensive NSM solution. The figure illustrates a simplified view of the way in which some of the components of the Security Onion work together.

A Security Onion Architecture

26.1.3 Analysis Tools

Security Onion integrates these various types of data and Intrusion Detection System (IDS) logs into a single platform through the following tools:

- Sguil – This provides a high-level console for investigating security alerts from a wide variety of sources. Sguil serves as a starting point in the investigation of security alerts. A wide variety of data sources are available to the cybersecurity analyst by pivoting directly from Sguil to other tools.

- Kibana – Kibana is an interactive dashboard interface to Elasticsearch data. It allows querying of NSM data and provides flexible visualizations of that data. It provides data exploration and machine learning data analysis features. It is possible to pivot from Sguil directly into Kibana to see contextualized displays based on the source and destination IP addresses that are associated with an alert. Search the internet and visit the elastic.co website to learn more about the many features of Kibana.

- Wireshark – This is a packet capture application that is integrated into the Security Onion suite. It can be opened directly from other tools and will display full packet captures relevant to an analysis.

- Zeek – This is a network traffic analyzer that serves as a security monitor. Zeek inspects all traffic on a network segment and enables in-depth analysis of that data. Pivoting from Sguil into Zeek provides access to very accurate transaction logs, file content, and customized output.

Note: Other Security Onion tools that are not shown in the figure are beyond the scope of this course. A full description of Security Onion and its components can be found at the Security Onion website.

26.1.4 Alert Generation

Security alerts are notification messages that are generated by NSM tools, systems, and security devices. Alerts can come in many forms depending on the source. For example, syslog provides support for severity ratings which can be used to alert cybersecurity analysts regarding events that require attention.

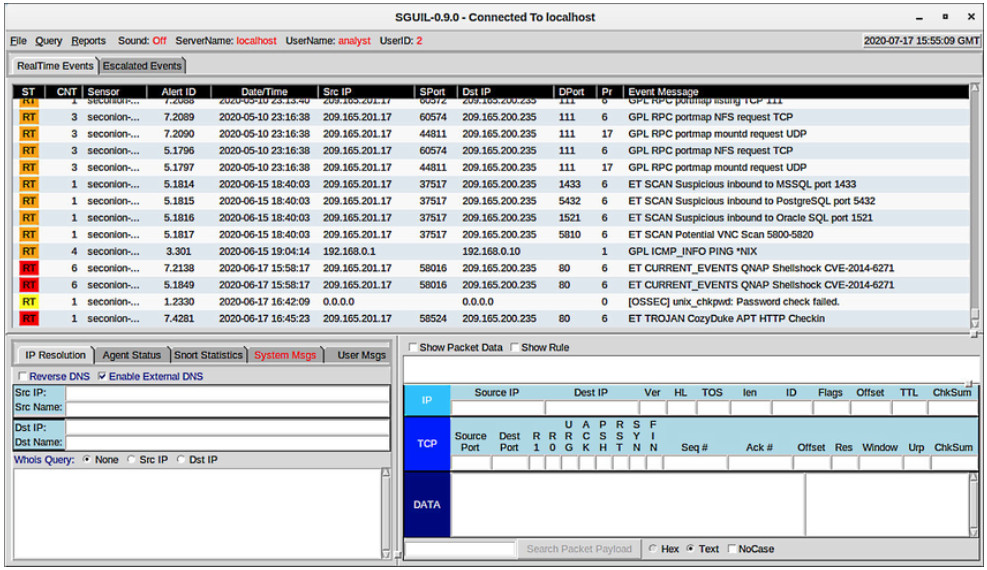

In Security Onion, Sguil provides a console that integrates alerts from multiple sources into a timestamped queue. A cybersecurity analyst can work through the security queue investigating, classifying, escalating, or retiring alerts. Instead of using a dedicated workflow management system such as Request Tracker for Incident Response (RTIR), a cybersecurity analyst would use the output of an application like Sguil to orchestrate an NSM investigation.

Alerts will generally include five-tuples information when available, as well as timestamps and information identifying which device or system generated the alert. Recall that the five-tuples includes the following information for tracking a conversation between a source and destination application:

- SrcIP – the source IP address for the event.

- SPort – the source (local) Layer 4 port for the event.

- DstIP – the destination IP for the event.

- DPort – the destination Layer 4 port for the event.

- Pr – the IP protocol number for the event.

Additional information could be whether a permit or deny decision was applied to the traffic, some captured data from the packet payload, or a hash value for a downloaded file, or any of a variety of data.

The figure shows the Sguil application window with the queue of alerts that are waiting to be investigated in the top portion of the interface.

Sguil Window

The fields available for the real-time events are as follows:

- ST – This is the status of the event. RT means real time. The event is color-coded by priority. The priorities are based on the category of the alert. There are four priority levels: very low, low, medium, and high. The colors range from light yellow to red as the priority increases.

- CNT – This is the count for the number of times this event has been detected for the same source and destination IP address. The system has determined that this set of events is correlated. Rather than reporting each in a potentially long series of correlated events in this window, the event is listed once with the number of times it has been detected in this column. High numbers here can represent a security problem or the need for tuning of the event signatures to limit the number of potentially spurious events that are being reported.

- Sensor – This is the agent reporting the event. The available sensors and their identifying numbers can be found in the Agent Status tab of the pane which appears below the events window on the left. These numbers are also used in the Alert ID column. From the Agent Status pane, we can see that OSSEC, pcap, and Snort sensors are reporting to Sguil. In addition, we can see the default hostnames for these sensors, which includes the monitoring interface. Note that each monitoring interface has both pcap and Snort data associated with it.

- Alert ID – This two-part number represents the sensor that has reported the problem and the event number for that sensor. We can see from the figure that the largest number of events that are displayed are from the OSSEC sensor (1). The OSSEC sensor has reported eight sets of correlated events. Of these events, 232 have been reported with event ID 1.24.

- Date/Time – This is the timestamp for the event. In the case of correlated events, it is the timestamp for the first event.

- Event Message – This is the identifying text for the event. This is configured in the rule that triggered the alert. The associated rule can be viewed in the right-hand pane, just above the packet data. To display the rule, the Show Rule checkbox must be selected.

Depending on the security technology, alerts can be generated based on rules, signatures, anomalies, or behaviors. No matter how they are generated, the conditions that trigger an alert must be predefined in some manner.

26.1.5 Rules and Alerts

Alerts can come from a number of sources:

- NIDS – Snort, Zeek, and Suricata

- HIDS – OSSEC, Wazuh

- Asset management and monitoring – Passive Asset Detection System (PADS)

- HTTP, DNS, and TCP transactions – Recorded by Zeek and pcaps

- Syslog messages – Multiple sources

The information found in the alerts that are displayed in Sguil will differ in message format because they come from different sources.

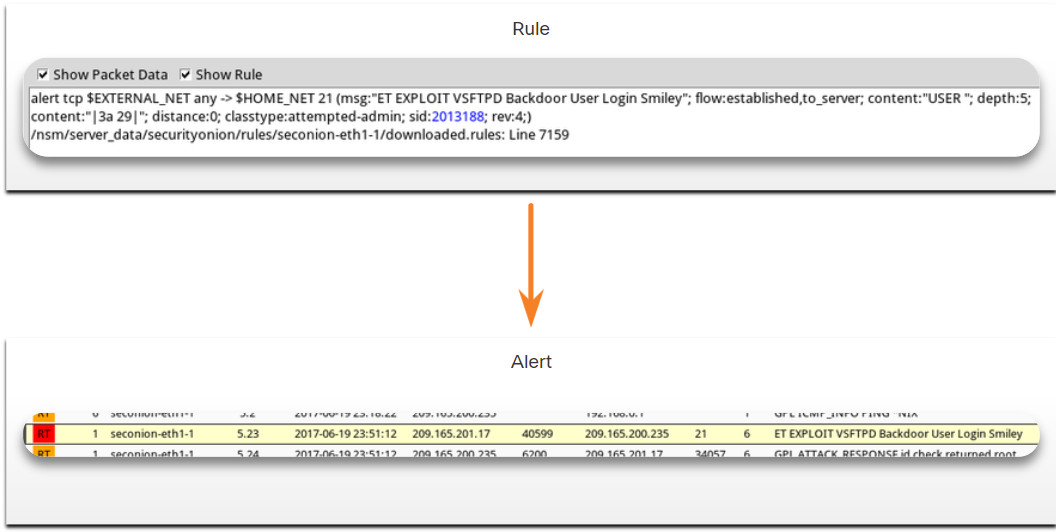

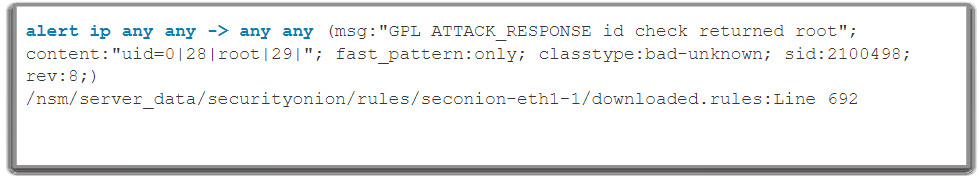

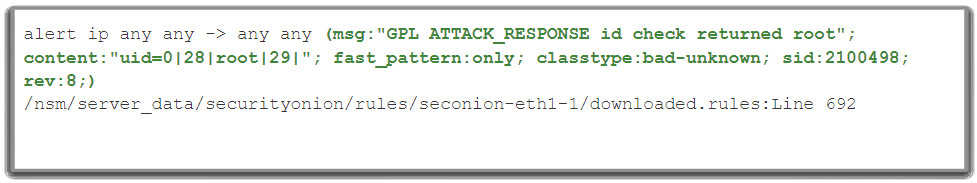

The Sguil alert in the figure was triggered by a rule that was configured in Snort. It is important for the cybersecurity analyst to be able to interpret what triggered the alert so that the alert can be investigated. For this reason, the cybersecurity analyst should understand the components of Snort rules, which are a major source of alerts in Security Onion.

Sguil Alert and the Associated Rule

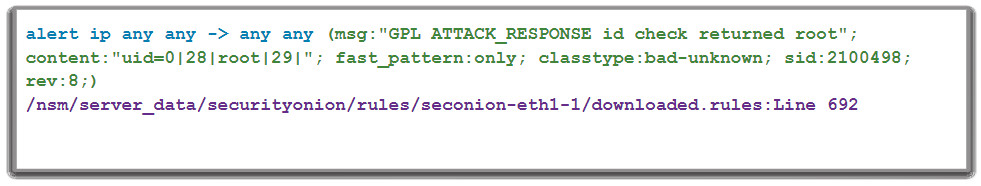

26.1.6 Snort Rule Structure

Snort rules consist of two sections, as shown in the figure: the rule header and the rule options. The rule header contains the action, protocol, source and destination IP addresses and netmasks, and the source and destination port information. The rule options section contains alert messages and information on which parts of the packet should be inspected to determine if the rule action should be taken. Rule Location is sometimes added by Sguil. Rule Location is the path to the file that contains the rule and the line number at which the rule appears so that it can be found and modified, or eliminated, if required.

Snort Rule Structure and Sguil-supplied Information

| Component | Example (shortened…) | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| rule header | alert ip any any -> any any | Contains the action to be taken, source and destination addresses and port, and the direction of traffic flow |

| rule options | (msg:”GPL ATTACK_RESPONSE ID CHECK RETURNED ROOT”;…) | Includes the message to be displayed, details of packet content, alert type, source ID, and additional details, such as a reference for the rule or vulnerability |

| rule location | /nsm/server_data/securityonion/rules/… | Added by Sguil to indicate the location of the rule in the Security Onion file structure and in the specified rule file |

The Rule Header

The rule header contains the action, protocol, addressing, and port information, as shown in the figure. In addition, the direction of flow that triggered the alert is indicated. The structure of the header portion is consistent between Snort alert rules.

Snort can be configured to use variables to represent internal and external IP addresses. These variables, $HOME_NET and $EXTERNAL_NET, appear in the Snort rules. They simplify the creation of rules by eliminating the need to specify specific addresses and masks for every rule. The values for these variables are configured in the snort.conf file. Snort also allows individual IP addresses, blocks of addresses, or lists of either to be specified in rules. Ranges of ports can be specified by separating the upper and lower values of the range with a colon. Other operators are also available.

Snort Rule Header Structure

| Component | Explanation |

|---|---|

| alert | the action to be taken is to issue an alert, other actions are log and pass |

| ip | the protocol |

| any any | the specified source is any IP address and any Layer 4 port |

| -> | the direction of flow is from the source to the destination |

| any any | the specified destination is any IP address and any Layer 4 port |

The Rule Options

The structure of the options section of the rule is variable. It is the portion of the rule that is enclosed in parenthesis, as shown in the figure. It contains the text message that identifies the alert. It also contains metadata about the alert, such as a URL that provides reference information for the alert. Other information can be included, such as the type of rule and a unique numeric identifier for the rule and the rule revision. In addition, features of the packet payload may be specified in the options. The Snort users manual, which can be found on the internet, provides details about rules and how to create them.

Snort rule messages may include the source of the rule. Three common sources for Snort rules are:

- GPL – Older Snort rules that were created by Sourcefire and distributed under a GPLv2. The GPL ruleset is not Cisco Talos certified. It includes Snort SIDs 3464 and below. The GPL ruleset is can be downloaded from the Snort website, and it is included in Security Onion.

- ET – Snort rules from Emerging Threats. Emerging Threats is a collection point for Snort rules from multiple sources. ET rules are open source under a BSD license. The ET ruleset contains rules from multiple categories. A set of ET rules is included with Security Onion. Emerging Threats is a division of Proofpoint, Inc.

- VRT – These rules are immediately available to subscribers and are released to registered users 30 days after they were created, with some limitations. They are now created and maintained by Cisco Talos.

Rules can be downloaded automatically from Snort.org using the PulledPork rule management utility that is included with Security Onion.

Alerts that are not generated by Snort rules are identified by the OSSEC or PADS tags, among others. In addition, custom local rules can be created.

Snort Rules Options Structure

| Component | Explanation |

|---|---|

| msg: | Text that describes the alert. |

| content: | Refers to content of the packet. In this case, an alert will be sent if the literal text “uid=0(root)” appears anywhere in the packet data. Values specifying the location of the text in the data payload can be provided. |

| reference: | This is not shown in the figure. It is often a link to a URL that provides more information on the rule. In this case, the sid is hyperlinked to the source of the rule on the internet. |

| classtype: | A category for the attack. Snort includes a set of default categories that have one of four priority values. |

| sid: | A unique numeric identifier for the rule. |

| rev: | The revision of the rule that is represented by the sid. |

26.1.7 Lab – Snort and Firewall Rules

Different security appliances and software perform different functions and record different events. As a consequence, the alerts that are generated by different appliances and software will also vary.

In this lab, to get familiar with firewall rules and IDS signatures you will:

- Perform live monitoring of IDS and events.

- Configure your own customized firewall rule to stop internal hosts from contacting a malware-hosting server.

- Craft a malicious packet and launch it against an internal target.

- Create a customized IDS rule to detect the customized attack and issue an alert based on it.

26.1.7 Lab – Snort and Firewall Rules

26.2 Overview of Alert Evaluation

26.2.1 The Need for Alert Evaluation

The threat landscape is constantly changing as new vulnerabilities are discovered and new threats evolve. As user and organizational needs change, so also does the attack surface. Threat actors have learned how to quickly vary features of their exploits in order to evade detection.

It is impossible to design measures to prevent all exploits. Exploits will inevitably evade protection measures, no matter how sophisticated they may be. Sometimes, the best that can be done is to detect exploits during or after they have occurred. Detection rules should be overly conservative. In other words, it is better to have alerts that are sometimes generated by innocent traffic, than it is to have rules that miss malicious traffic. For this reason, it is necessary to have skilled cybersecurity analysts investigate alerts to determine if an exploit has actually occurred.

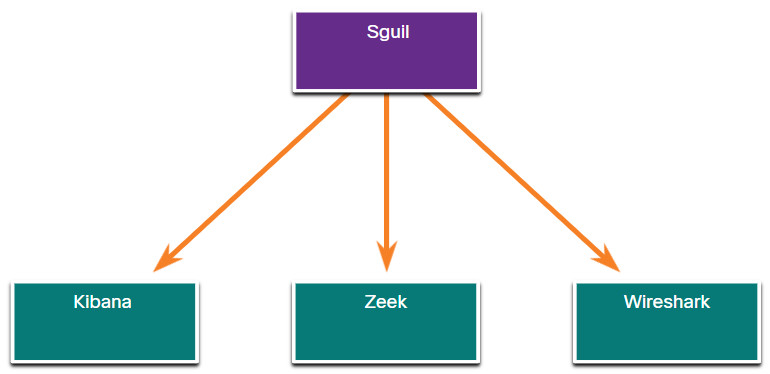

Tier 1 cybersecurity analysts will typically work through queues of alerts in a tool like Sguil, pivoting to tools like Zeek, Wireshark, and Kibana to verify that an alert represents an actual exploit.

Primary Tools for the Tier 1 Cybersecurity Analyst

26.2.2 Evaluating Alerts

Security incidents are classified using a scheme borrowed from medical diagnostics. This classification scheme is used to guide actions and to evaluate diagnostic procedures. For example, when a patient visits a doctor for a routine examination, one of the doctor’s tasks is to determine whether the patient is sick. One of the outcomes can be a correct determination that disease is present and the patient is sick. Another outcome can be that there is no disease and the patient is healthy.

The concern is that either diagnosis can be accurate, or true, or inaccurate, or false. For example, the doctor could miss the signs of disease and make the incorrect determination that the patient is well when they are in fact sick. Another possible error is to rule that a patient is sick when that patient is in fact healthy. False diagnoses are either costly or dangerous.

In network security analysis, the cybersecurity analyst is presented with an alert. This is similar to a patient going to the doctor and saying, “I am sick.” The cybersecurity analyst, like the doctor, needs to determine if this diagnosis is true. The cybersecurity analyst asks, “The system says that an exploit has occurred. Is this true?”

Alerts can be classified as follows:

- True Positive: The alert has been verified to be an actual security incident.

- False Positive: The alert does not indicate an actual security incident. Benign activity that results in a false positive is sometimes referred to as a benign trigger.

An alternative situation is that an alert was not generated. The absence of an alert can be classified as:

- True Negative: No security incident has occurred. The activity is benign.

- False Negative: An undetected incident has occurred.

| When an alert is issued, it will receive one of four possible classifications | ||

|---|---|---|

| True | False | |

| Positive (Alert exists) | Incident occurred | No incident occurred |

| Negative (No alert exists) | No incident occurred | Incident occurred |

| Note: “True” events are desirable. “False” events are undesirable and potentially dangerous. | ||

True positives are the desired type of alert. They mean that the rules that generate alerts have worked correctly.

False positives are not desirable. Although they do not indicate that an undetected exploit has occurred, they are costly because cybersecurity analysts must investigate false alarms; therefore, time is taken away from investigation of alerts that indicate true exploits.

True negatives are desirable. They indicate that benign normal traffic is correctly ignored, and erroneous alerts are not being issued.

False negatives are dangerous. They indicate that exploits are not being detected by the security systems that are in place. These incidents could go undetected for a long time, and ongoing data loss and damage could result.

Benign events are those that should not trigger alerts. Excess benign events indicate that some rules or other detectors need to be improved or eliminated.

When true positives are suspected, a cybersecurity analyst is sometimes required to escalate the alert to a higher level for investigation. The investigator will move forward with the investigation in order to confirm the incident and identify any potential damage that may have been caused. This information will be used by more senior security personnel who will work to isolate the damage, address vulnerabilities, mitigate the threat, and deal with reporting requirements.

A cybersecurity analyst may also be responsible for informing security personnel that false positives are occurring to the extent that the cybersecurity analyst’s time is seriously impacted. This situation indicates that security monitoring systems need to be tuned to become more efficient. Legitimate changes in the network configuration or newly downloaded detection rules could result in a sudden spike in false positives as well.

False negatives may be discovered well after an exploit has occurred. This can happen through retrospective security analysis (RSA). RSA can occur when newly obtained rules or other threat intelligence is applied to archived network security data. For this reason, it is important to monitor threat intelligence to learn of new vulnerabilities and exploits and to evaluate the likelihood that the network was vulnerable to them at some time in the past. In addition, the exploit needs to be evaluated regarding the potential damage that the enterprise could suffer. It may be determined that adding new mitigation techniques is sufficient, or that a more detailed analysis should be conducted.

26.2.3 Deterministic Analysis and Probabilistic Analysis

Statistical techniques can be used to evaluate the risk that exploits will be successful in a given network. This type of analysis can help decision makers to better evaluate the cost of mitigating a threat with the damage that an exploit could cause.

Two general approaches used to do this are deterministic and probabilistic analysis. Deterministic analysis evaluates risk based on what is known about a vulnerability. It assumes that for an exploit to be successful all prior steps in the exploit process must also be successful. This type of risk analysis can only describe the worst case. However, many threat actors, although aware of the process to carry out an exploit, may lack the knowledge or expertise to successfully complete each step on the path to a successful exploit. This can give the cybersecurity analyst an opportunity to detect the exploit and stop it before it proceeds any further.

Probabilistic analysis estimates the potential success of an exploit by estimating the likelihood that if one step in an exploit has successfully been completed that the next step will also be successful. Probabilistic analysis is especially useful in real-time network security analysis in which numerous variables are at play and a given threat actor can make unknown decisions as an exploit is pursued.

Probabilistic analysis relies on statistical techniques that are designed to estimate the probability that an event will occur based on the likelihood that prior events will occur. Using this type of analysis, the most likely paths that an exploit will take can be estimated and the attention of security personnel can be focused on preventing or detecting the most likely exploit.

In a deterministic analysis, all of the information to accomplish an exploit is assumed to be known. The characteristics of the exploit, such as the use of specific port numbers, are known either from other instances of the exploit, or because standardized ports are in use. In probabilistic analysis, it is assumed that the port numbers that will be used can only be predicted with some degree of confidence. In this situation, an exploit that uses dynamic port numbers, for example, cannot be analyzed deterministically. Such exploits have been optimized to avoid detection by firewalls that use static rules.

The two approaches are summarized below.

- Deterministic Analysis – For an exploit to be successful, all prior steps in the exploit must also be successful. The cybersecurity analyst knows the steps for a successful exploit.

- Probabilistic Analysis – Statistical techniques are used to determine the probability that a successful exploit will occur based on the likelihood that each step in the exploit will succeed.

26.3 Evaluating Alerts Summary

26.3.1 What did I learn in this module?

Sources of Alerts

Security Onion is an open-source suite of Network Security Monitoring (NSM) tools that run on an Ubuntu Linux distribution. Security Onion tools provide three core functions for the cybersecurity analyst: full packet capture and data types, network-based and host-based intrusion detection systems, and alert analyst tools. Some components of Security Onion are owned and maintained by corporations, such as Cisco and Riverbend Technologies, but are made available as open source.

Security Onion contains many components. It is an integrated environment which is designed to simplify the deployment of a comprehensive NSM solution. Security Onion integrates these various types of data and Intrusion Detection System (IDS) logs into a single platform through the following tools: Sguil – serves as a starting point in the investigation of security alerts. Kibana – Kibana is an interactive dashboard interface to Elasticsearch data. It allows querying of NSM data and provides flexible visualizations of that data. The Wireshark packet capture application is integrated into the Security Onion suite. Zeek is a network traffic analyzer that serves as a security monitor. Zeek inspects all traffic on a network segment and enables in-depth analysis of that data.

Security alerts are notification messages that are generated by NSM tools, systems, and security devices. In Security Onion, Sguil provides a console that integrates alerts from multiple sources into a timestamped queue. A cybersecurity analyst can work through the security queue investigating, classifying, escalating, or retiring alerts.

Alerts will generally include five-tuples information when available, as well as timestamps and information that identifies which device or system generated the alert. Depending on the security technology, alerts can be generated based on rules, signatures, anomalies, or behaviors. Alerts can come from a number of sources, such as NIDS, asset management and monitoring, HTTP, DNS, and TCP transactions, and Syslog messages.

Snort is a Network Intrusion Detection System (NIDS). It is an important source of the alert data that is indexed in the Sguil analysis tool. It uses rules to identify potentially malicious traffic. Snort rules consist of two sections: the rule header and the rule options. The rule header contains the action, protocol, source and destination IP addresses and netmasks, and the source and destination port information. The rule options section contains alert messages and information on which parts of the packet should be inspected to determine if the rule action should be taken. The structure of the options section of the rule is variable.

Overview of Alert Evaluation

The threat landscape is constantly changing as new vulnerabilities are discovered and new threats evolve. As user and organizational needs change, so also does the attack surface. Threat actors have learned how to quickly vary features of their exploits in order to evade detection. Detection rules should be overly conservative. It is better to have alerts that are sometimes generated by innocent traffic, than it is to have rules that miss malicious traffic. For this reason, it is necessary to have skilled cybersecurity analysts investigate alerts to determine if an exploit has actually occurred.

Security incidents are classified using a scheme borrowed from medical diagnostics. This classification scheme is used to guide actions and to evaluate diagnostic procedures. The concern is that a diagnosis can be either accurate, or true, or inaccurate, or false. Alerts can be classified as True Positive (The alert has been verified to be an actual security incident) or False Positive (The alert does not indicate an actual security incident). An alternative situation is that an alert was not generated. The absence of an alert can be classified as: True Negative (No security incident has occurred. The activity is benign.) and False Negative (An undetected incident has occurred). True Positives and True Negatives are desirable. False Positives are not desirable but unavoidable, and False Negatives are dangerous.

Statistical techniques can be used to evaluate the risk that exploits will be successful in a given network. This type of analysis can help decision makers to better evaluate the cost of mitigating a threat versus the damage that an exploit could cause. Two general approaches that are used to do this are deterministic and probabilistic analysis. Deterministic analysis evaluates risk based on what is known about a vulnerability. It assumes that for an exploit to be successful all prior steps in the exploit process must also be successful. This type of risk analysis can only describe the worst case. Probabilistic analysis estimates the potential success of an exploit by estimating the likelihood that if one step in an exploit has successfully been completed that the next step will also be successful. Probabilistic analysis is especially useful in real-time network security analysis in which numerous variables are at play and a given threat actor can make unknown decisions as an exploit is pursued.