9.0 Introduction

9.0.1 Why Should I Take this Module?

Welcome to Transport Layer! The transport layer is where, as the name implies, data is transported from one host to another. This is where your network really gets moving! The transport layer uses two protocols: TCP and UDP. Think of TCP as getting a registered letter in the mail. You have to sign for it before the mail carrier will let you have it. UDP is more like a regular, stamped letter. Both protocols have there place in delivering data between a source and a destination. This topic dives into how TCP and UDP work in the transport layer.

9.0.2 What Will I Learn in this Module?

Module Title: The Transport Layer

Module Objective: Explain how transport layer protocols support network functionality.

| Topic Title | Topic Objective |

|---|---|

| Transport Layer Characteristics | Explain how transport layer protocols support network communication. |

| Transport Layer Session Establishment | Explain how the transport layer establishes communication sessions. |

| Transport Layer Reliability | Explain how the transport layer establishes reliable communications. |

9.1 Transport Layer Characteristics

9.1.1 Role of the Transport Layer

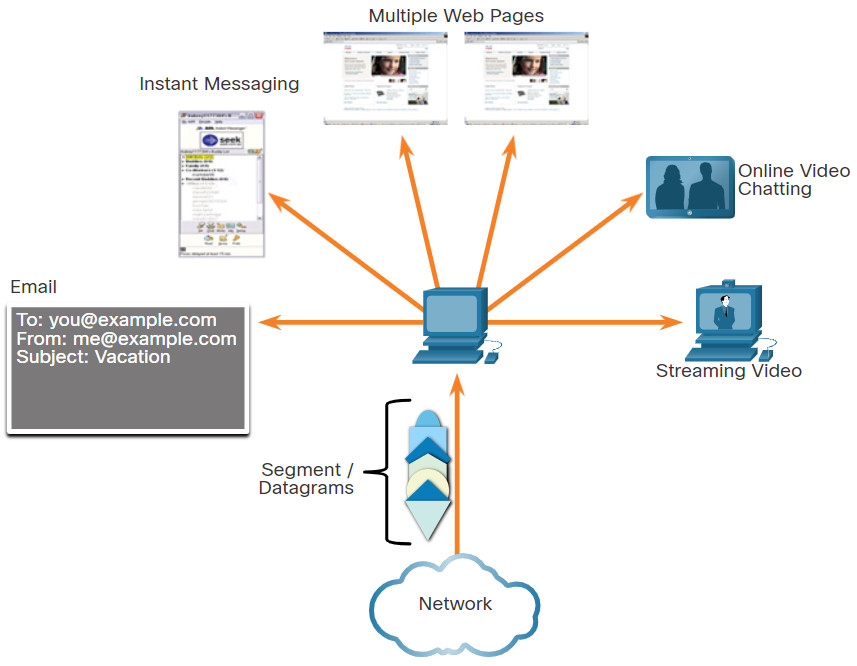

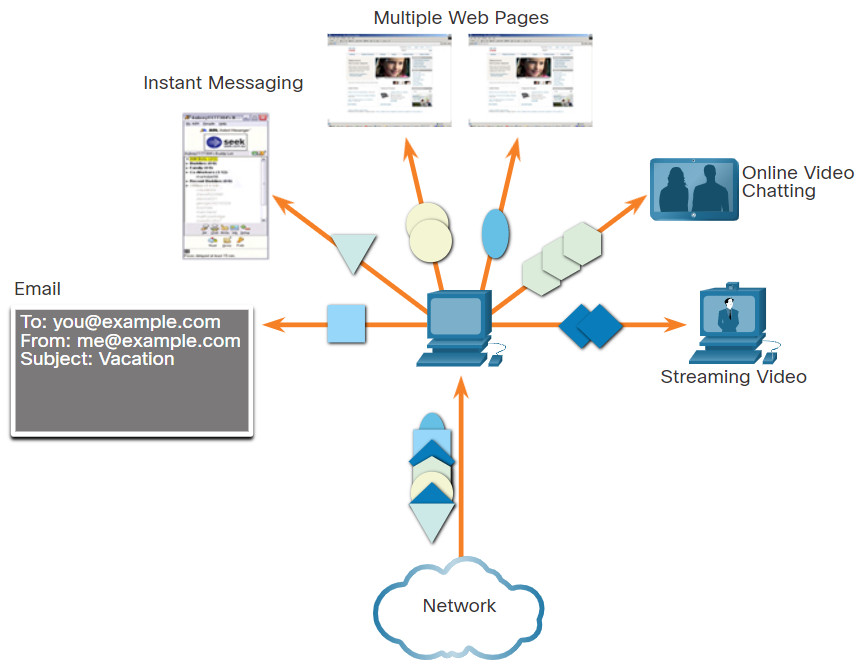

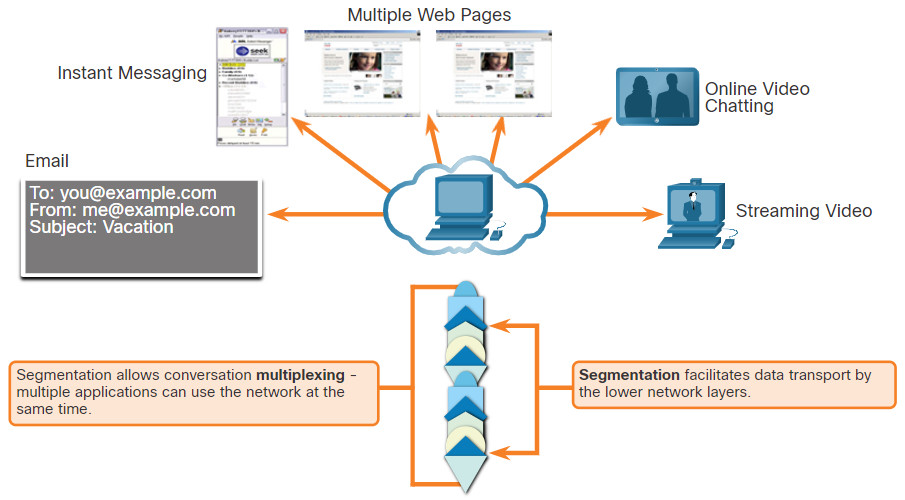

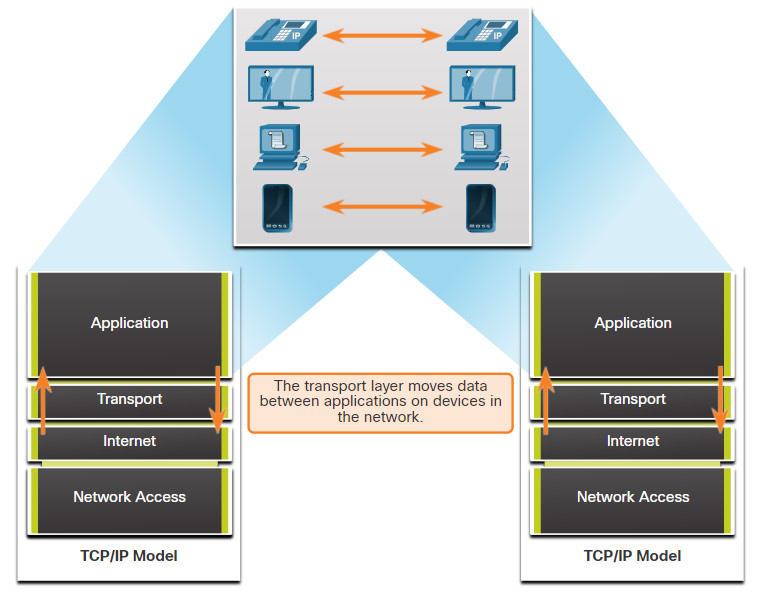

Application layer programs generate data that must be exchanged between source and destination hosts. The transport layer is responsible for logical communications between applications running on different hosts. This may include services such as establishing a temporary session between two hosts and the reliable transmission of information for an application.

As shown in the figure, the transport layer is the link between the application layer and the lower layers that are responsible for network transmission.

The transport layer has no knowledge of the destination host type, the type of media over which the data must travel, the path taken by the data, the congestion on a link, or the size of the network.

The transport layer includes two protocols:

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

- User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

9.1.2 Transport Layer Responsibilities

The transport layer has many responsibilities.

9.1.3 Transport Layer Protocols

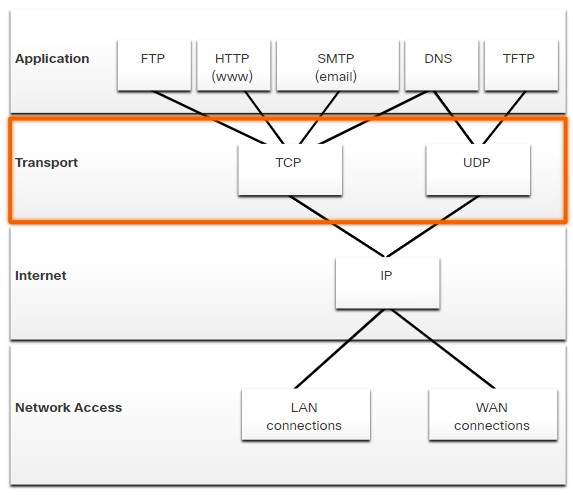

IP is concerned only with the structure, addressing, and routing of packets. IP does not specify how the delivery or transportation of the packets takes place.

Transport layer protocols specify how to transfer messages between hosts, and are responsible for managing reliability requirements of a conversation. The transport layer includes the TCP and UDP protocols.

Different applications have different transport reliability requirements. Therefore, TCP/IP provides two transport layer protocols, as shown in the figure.

9.1.4 Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

IP is concerned only with the structure, addressing, and routing of packets, from original sender to final destination. IP is not responsible for guaranteeing delivery or determining whether a connection between the sender and receiver needs to be established.

TCP is considered a reliable, full-featured transport layer protocol, which ensures that all of the data arrives at the destination. TCP includes fields which ensure the delivery of the application data. These fields require additional processing by the sending and receiving hosts.

Note: TCP divides data into segments.

TCP transport is analogous to sending packages that are tracked from source to destination. If a shipping order is broken up into several packages, a customer can check online to see the order of the delivery.

TCP provides reliability and flow control using these basic operations:

- Number and track data segments transmitted to a specific host from a specific application

- Acknowledge received data

- Retransmit any unacknowledged data after a certain amount of time

- Sequence data that might arrive in wrong order

- Send data at an efficient rate that is acceptable by the receiver

In order to maintain the state of a conversation and track the information, TCP must first establish a connection between the sender and the receiver. This is why TCP is known as a connection-oriented protocol.

Click Play in the figure to see how TCP segments and acknowledgments are transmitted between sender and receiver.

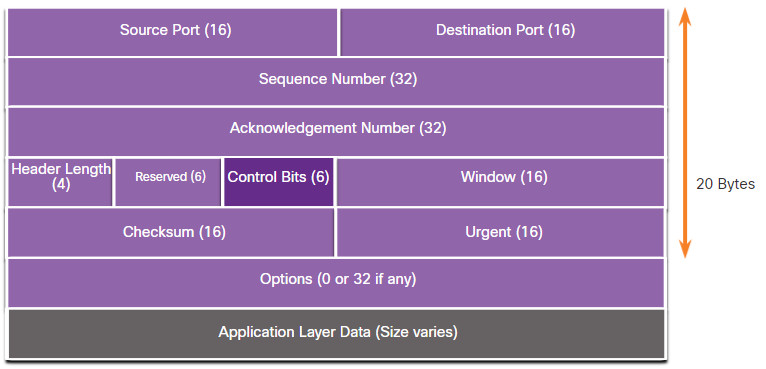

9.1.5 TCP Header

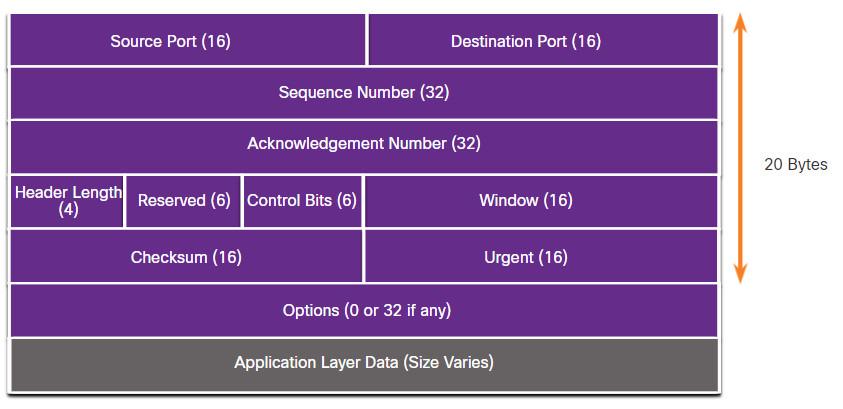

TCP is a stateful protocol which means it keeps track of the state of the communication session. To track the state of a session, TCP records which information it has sent and which information has been acknowledged. The stateful session begins with the session establishment and ends with the session termination.

A TCP segment adds 20 bytes (i.e., 160 bits) of overhead when encapsulating the application layer data. The figure shows the fields in a TCP header.

9.1.6 TCP Header Fields

The table identifies and describes the ten fields in a TCP header.

| TCP Header Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Source Port | A 16-bit field used to identify the source application by port number. |

| Destination Port | A 16-bit field used to identify the destination application by port number. |

| Sequence Number | A 32-bit field used for data reassembly purposes. |

| Acknowledgment Number | A 32-bit field used to indicate that data has been received and the next byte expected from the source. |

| Header Length | A 4-bit field known as ʺdata offsetʺ that indicates the length of the TCP segment header. |

| Reserved | A 6-bit field that is reserved for future use. |

| Control bits | A 6-bit field that includes bit codes, or flags, which indicate the purpose and function of the TCP segment. |

| Window size | A 16-bit field used to indicate the number of bytes that can be accepted at one time. |

| Checksum | A 16-bit field used for error checking of the segment header and data. |

| Urgent | A 16-bit field used to indicate if the contained data is urgent. |

9.1.7 User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

UDP is a simpler transport layer protocol than TCP. It does not provide reliability and flow control, which means it requires fewer header fields. Because the sender and the receiver UDP processes do not have to manage reliability and flow control, this means UDP datagrams can be processed faster than TCP segments. UDP provides the basic functions for delivering datagrams between the appropriate applications, with very little overhead and data checking.

Note: UDP divides data into datagrams that are also referred to as segments.

UDP is a connectionless protocol. Because UDP does not provide reliability or flow control, it does not require an established connection. Because UDP does not track information sent or received between the client and server, UDP is also known as a stateless protocol.

UDP is also known as a best-effort delivery protocol because there is no acknowledgment that the data is received at the destination. With UDP, there are no transport layer processes that inform the sender of a successful delivery.

UDP is like placing a regular, nonregistered, letter in the mail. The sender of the letter is not aware of the availability of the receiver to receive the letter. Nor is the post office responsible for tracking the letter or informing the sender if the letter does not arrive at the final destination.

Click Play in the figure to see an animation of UDP datagrams being transmitted from sender to receiver.

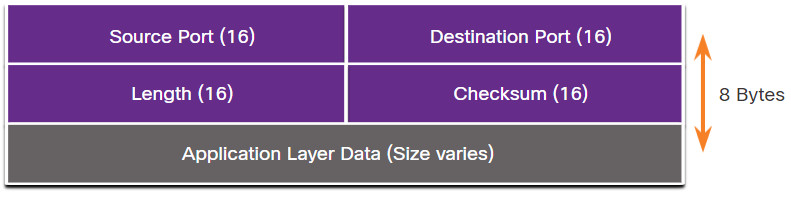

9.1.8 UDP Header

UDP is a stateless protocol, meaning neither the client, nor the server, tracks the state of the communication session. If reliability is required when using UDP as the transport protocol, it must be handled by the application.

One of the most important requirements for delivering live video and voice over the network is that the data continues to flow quickly. Live video and voice applications can tolerate some data loss with minimal or no noticeable effect, and are perfectly suited to UDP.

The blocks of communication in UDP are called datagrams, or segments. These datagrams are sent as best effort by the transport layer protocol.

The UDP header is far simpler than the TCP header because it only has four fields and requires 8 bytes (i.e., 64 bits). The figure shows the fields in a UDP header.

9.1.9 UDP Header Fields

The table identifies and describes the four fields in a UDP header.

| UDP Header Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Source Port | A 16-bit field used to identify the source application by port number. |

| Destination Port | A 16-bit field used to identify the destination application by port number. |

| Length | A 16-bit field that indicates the length of the UDP datagram header. |

| Checksum | A 16-bit field used for error checking of the datagram header and data. |

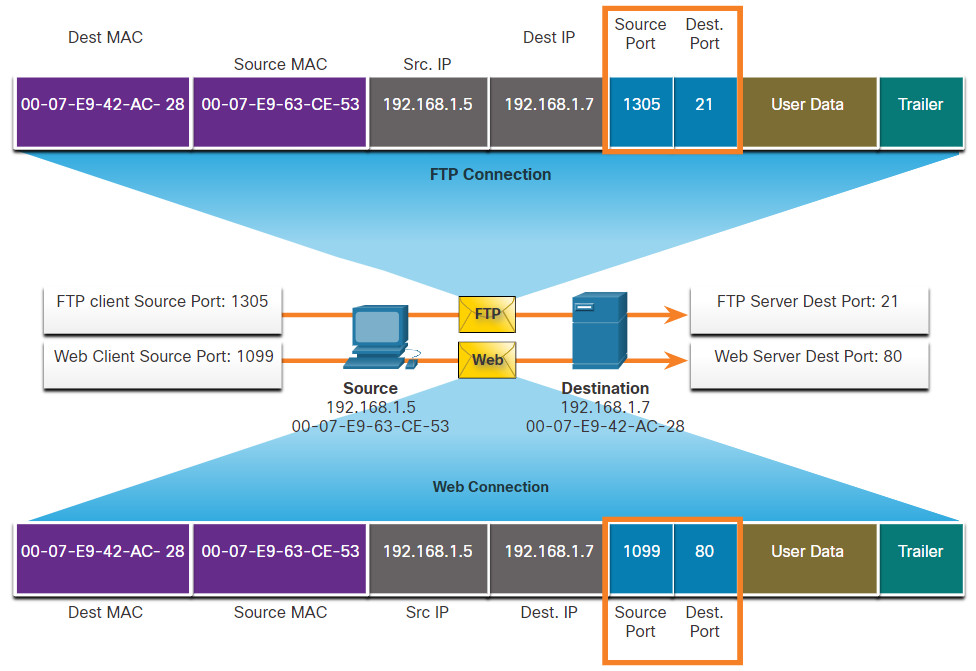

9.1.10 Socket Pairs

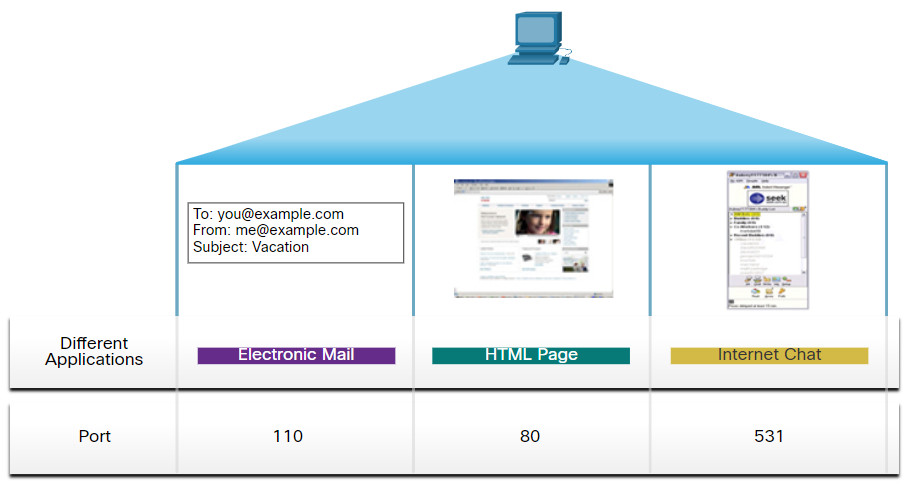

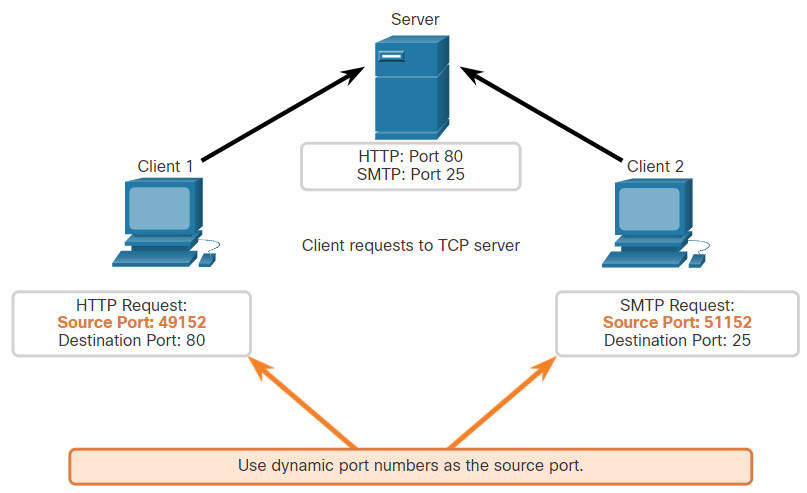

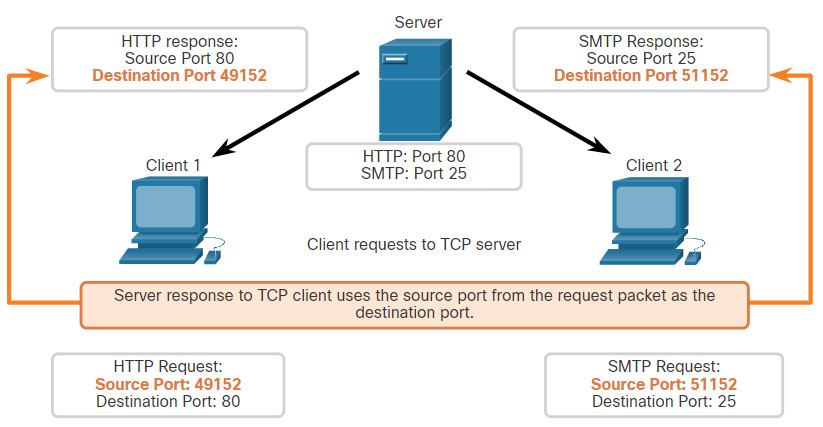

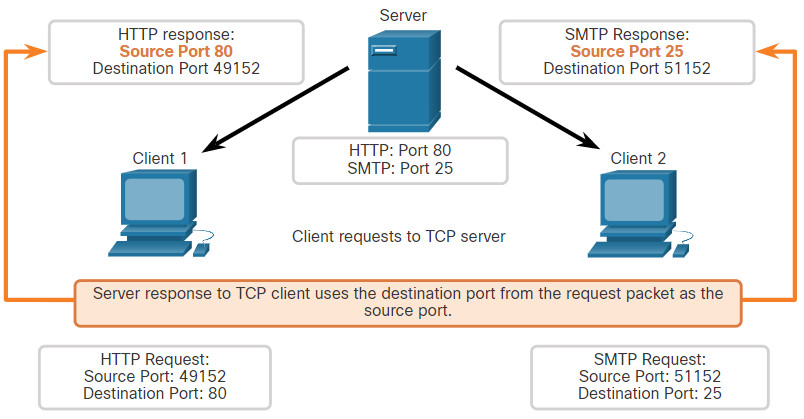

The source and destination ports are placed within the segment. The segments are then encapsulated within an IP packet. The IP packet contains the IP address of the source and destination. The combination of the source IP address and source port number, or the destination IP address and destination port number is known as a socket.

In the example in the figure, the PC is simultaneously requesting FTP and web services from the destination server.

In the example, the FTP request generated by the PC includes the Layer 2 MAC addresses and the Layer 3 IP addresses. The request also identifies the source port number 1305 (i.e., dynamically generated by the host) and destination port, identifying the FTP services on port 21. The host also has requested a web page from the server using the same Layer 2 and Layer 3 addresses. However, it is using the source port number 1099 (i.e., dynamically generated by the host) and destination port identifying the web service on port 80.

The socket is used to identify the server and service being requested by the client. A client socket might look like this, with 1099 representing the source port number: 192.168.1.5:1099

The socket on a web server might be 192.168.1.7:80

Together, these two sockets combine to form a socket pair: 192.168.1.5:1099, 192.168.1.7:80

Sockets enable multiple processes, running on a client, to distinguish themselves from each other, and multiple connections to a server process to be distinguished from each other.

The source port number acts as a return address for the requesting application. The transport layer keeps track of this port and the application that initiated the request so that when a response is returned, it can be forwarded to the correct application.

9.2 Transport Layer Session Establishment

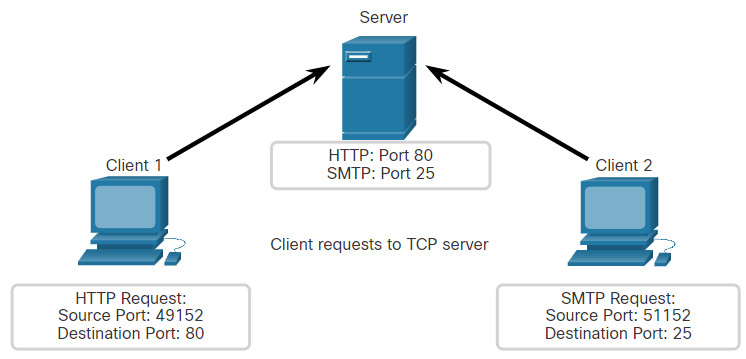

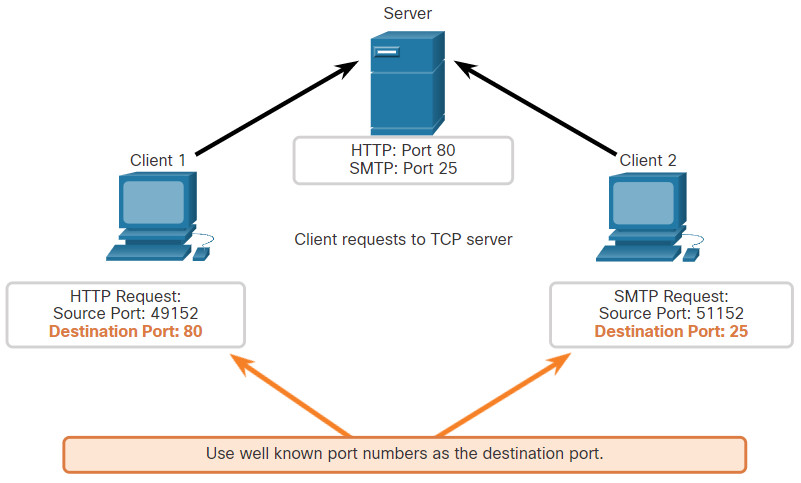

9.2.1 TCP Server Processes

You already know the fundamentals of TCP. Understanding the role of port numbers will help you to grasp the details of the TCP communication process. In this topic, you will also learn about the TCP three-way handshake and session termination processes.

Each application process running on a server is configured to use a port number. The port number is either automatically assigned or configured manually by a system administrator.

An individual server cannot have two services assigned to the same port number within the same transport layer services. For example, a host running a web server application and a file transfer application cannot have both configured to use the same port, such as TCP port 80.

An active server application assigned to a specific port is considered open, which means that the transport layer accepts, and processes segments addressed to that port. Any incoming client request addressed to the correct socket is accepted, and the data is passed to the server application. There can be many ports open simultaneously on a server, one for each active server application.

9.2.2 TCP Connection Establishment

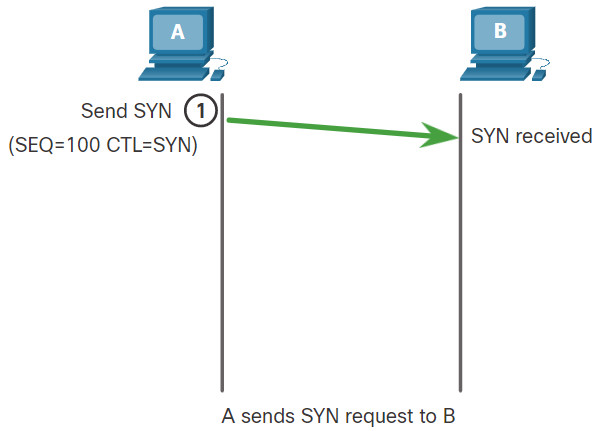

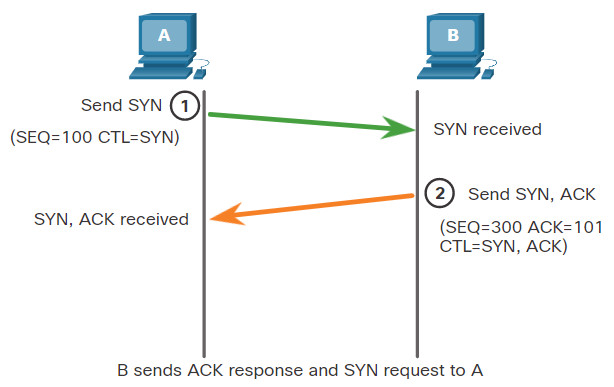

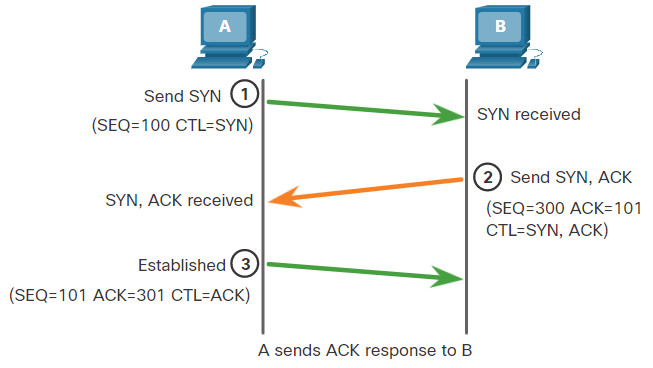

In some cultures, when two persons meet, they often greet each other by shaking hands. Both parties understand the act of shaking hands as a signal for a friendly greeting. Connections on the network are similar. In TCP connections, the host client establishes the connection with the server using the three-way handshake process.

The three-way handshake validates that the destination host is available to communicate. In this example, host A has validated that host B is available.

9.2.3 Session Termination

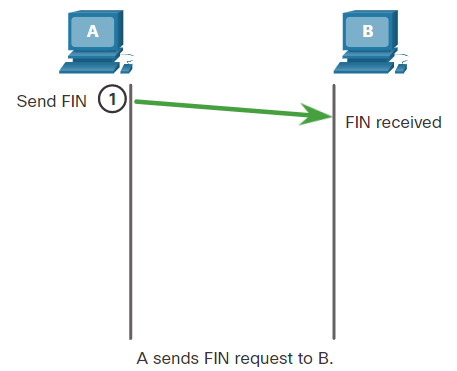

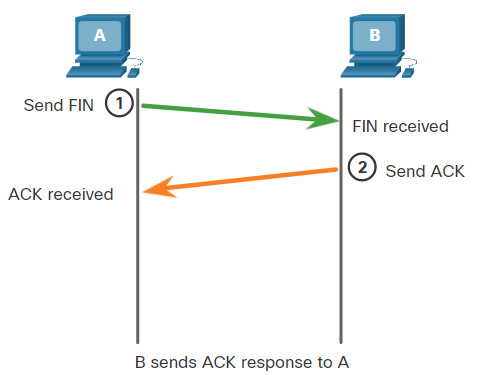

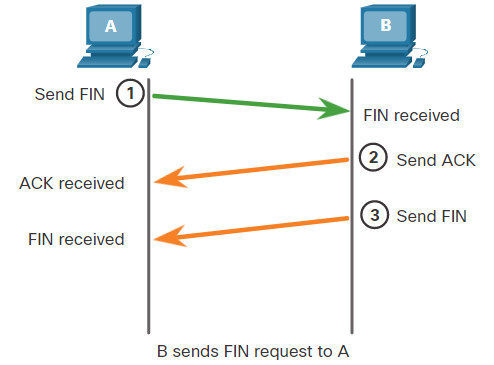

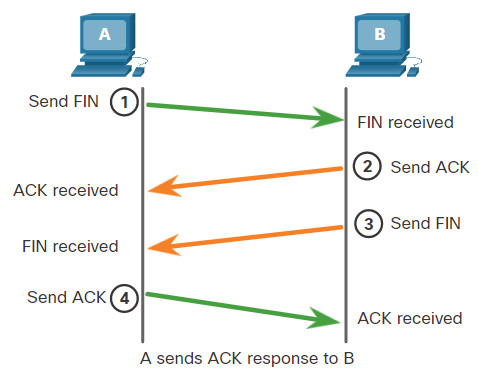

To close a connection, the Finish (FIN) control flag must be set in the segment header. To end each one-way TCP session, a two-way handshake, consisting of a FIN segment and an Acknowledgment (ACK) segment, is used. Therefore, to terminate a single conversation supported by TCP, four exchanges are needed to end both sessions. Either the client or the server can initiate the termination.

In the example, the terms client and server are used as a reference for simplicity, but any two hosts that have an open session can initiate the termination process.

When all segments have been acknowledged, the session is closed.

9.2.4 TCP Three-way Handshake Analysis

Hosts maintain state, track each data segment within a session, and exchange information about what data is received using the information in the TCP header. TCP is a full-duplex protocol, where each connection represents two one-way communication sessions. To establish the connection, the hosts perform a three-way handshake. As shown in the figure, control bits in the TCP header indicate the progress and status of the connection.

These are the functions of the three-way handshake:

- It establishes that the destination device is present on the network.

- It verifies that the destination device has an active service and is accepting requests on the destination port number that the initiating client intends to use.

- It informs the destination device that the source client intends to establish a communication session on that port number.

After the communication is completed the sessions are closed, and the connection is terminated. The connection and session mechanisms enable TCP reliability function.

Control Bits Field

The six bits in the Control Bits field of the TCP segment header are also known as flags. A flag is a bit that is set to either on or off.

The six control bits flags are as follows:

- URG – Urgent pointer field significant

- ACK – Acknowledgment flag used in connection establishment and session termination

- PSH – Push function

- RST – Reset the connection when an error or timeout occurs

- SYN – Synchronize sequence numbers used in connection establishment

- FIN – No more data from sender and used in session termination

Search the internet to learn more about the PSH and URG flags.

9.2.5 Video – TCP 3-Way Handshake

Watch the video to learn more about the TCP 3-way handshake.

9.2.6 Lab – Using Wireshark to Observe the TCP 3-Way Handshake

In this lab, you will complete the following objectives:

- Part 1: Prepare the Hosts to Capture the Traffic

- Part 2: Analyze the Packets using Wireshark

- Part 3: View the Packets using tcpdump

9.2.6 Lab – Using Wireshark to Observe the TCP 3-Way Handshake

9.3 Transport Layer Reliability

9.3.1 TCP Reliability – Guaranteed and Ordered Delivery

The reason that TCP is the better protocol for some applications is because, unlike UDP, it resends dropped packets and numbers packets to indicate their proper order before delivery. TCP can also help maintain the flow of packets so that devices do not become overloaded. This topic covers these features of TCP in detail.

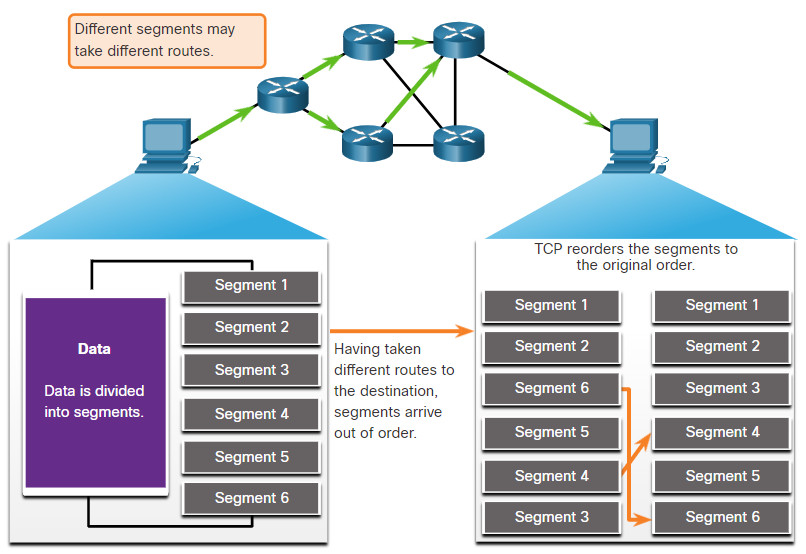

There may be times when TCP segments do not arrive at their destination. Other times, the TCP segments might arrive out of order. For the original message to be understood by the recipient, all the data must be received and the data in these segments must be reassembled into the original order. Sequence numbers are assigned in the header of each packet to achieve this goal. The sequence number represents the first data byte of the TCP segment.

During session setup, an initial sequence number (ISN) is set. This ISN represents the starting value of the bytes that are transmitted to the receiving application. As data is transmitted during the session, the sequence number is incremented by the number of bytes that have been transmitted. This data byte tracking enables each segment to be uniquely identified and acknowledged. Missing segments can then be identified.

The ISN does not begin at one but is effectively a random number. This is to prevent certain types of malicious attacks. For simplicity, we will use an ISN of 1 for the examples in this chapter.

Segment sequence numbers indicate how to reassemble and reorder received segments, as shown in the figure.

TCP Segments Are Reordered at the Destination

The receiving TCP process places the data from a segment into a receiving buffer. Segments are then placed in the proper sequence order and passed to the application layer when reassembled. Any segments that arrive with sequence numbers that are out of order are held for later processing. Then, when the segments with the missing bytes arrive, these segments are processed in order.

9.3.2 Video – TCP Reliability – Sequence Numbers and Acknowledgements

One of the functions of TCP is to ensure that each segment reaches its destination. The TCP services on the destination host acknowledge the data that have been received by the source application.

Click Play in the figure to view a lesson on TCP sequence numbers and acknowledgments.

9.3.3 TCP Reliability – Data Loss and Retransmission

No matter how well designed a network is, data loss occasionally occurs. TCP provides methods of managing these segment losses. Among these is a mechanism to retransmit segments for unacknowledged data.

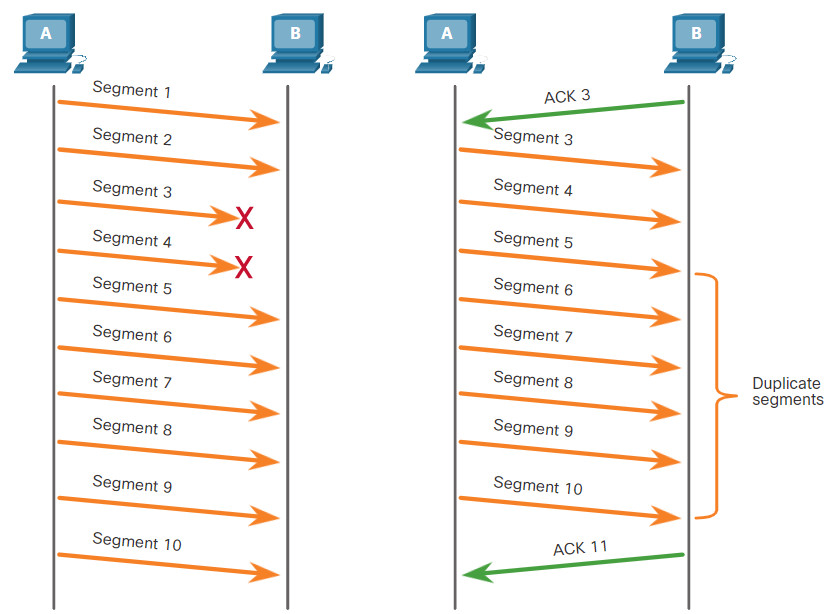

The sequence (SEQ) number and acknowledgement (ACK) number are used together to confirm receipt of the bytes of data contained in the transmitted segments. The SEQ number identifies the first byte of data in the segment being transmitted. TCP uses the ACK number sent back to the source to indicate the next byte that the receiver expects to receive. This is called expectational acknowledgement.

Prior to later enhancements, TCP could only acknowledge the next byte expected. For example, in the figure, using segment numbers for simplicity, host A sends segments 1 through 10 to host B. If all the segments arrive except for segments 3 and 4, host B would reply with acknowledgment specifying that the next segment expected is segment 3. Host A has no idea if any other segments arrived or not. Host A would, therefore, resend segments 3 through 10. If all the resent segments arrived successfully, segments 5 through 10 would be duplicates. This can lead to delays, congestion, and inefficiencies.

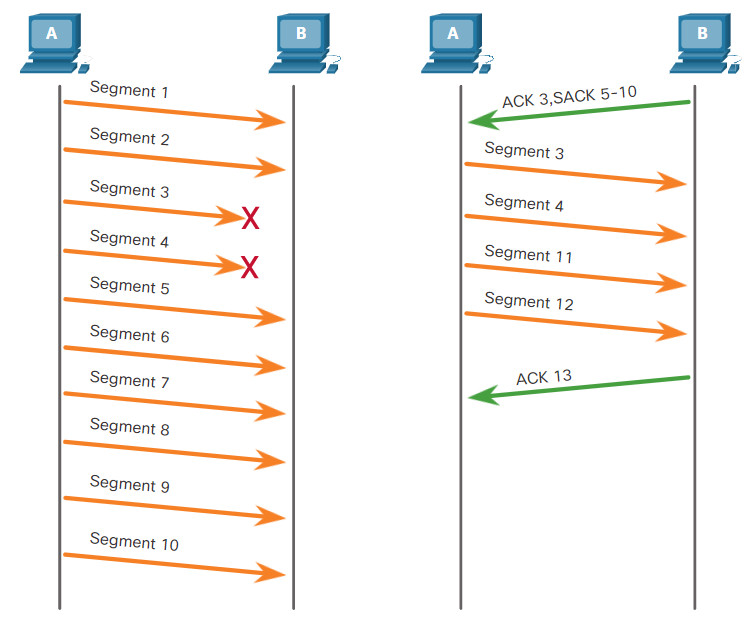

Host operating systems today typically employ an optional TCP feature called selective acknowledgment (SACK), negotiated during the three-way handshake. If both hosts support SACK, the receiver can explicitly acknowledge which segments (bytes) were received including any discontinuous segments. The sending host would therefore only need to retransmit the missing data. For example, in the next figure, again using segment numbers for simplicity, host A sends segments 1 through 10 to host B. If all the segments arrive except for segments 3 and 4, host B can acknowledge that it has received segments 1 and 2 (ACK 3), and selectively acknowledge segments 5 through 10 (SACK 5-10). Host A would only need to resend segments 3 and 4.

Note: TCP typically sends ACKs for every other packet, but other factors beyond the scope of this topic may alter this behavior.

TCP uses timers to know how long to wait before resending a segment. In the figure, play the video and click the link to download the PDF file. The video and PDF file examine TCP data loss and retransmission.

9.3.4 Video – TCP Reliability – Data Loss and Retransmission

Click Play in the figure to view a lesson on TCP retransmission.

9.3.5 TCP Flow Control – Window Size and Acknowledgments

TCP also provides mechanisms for flow control. Flow control is the amount of data that the destination can receive and process reliably. Flow control helps maintain the reliability of TCP transmission by adjusting the rate of data flow between source and destination for a given session. To accomplish this, the TCP header includes a 16-bit field called the window size.

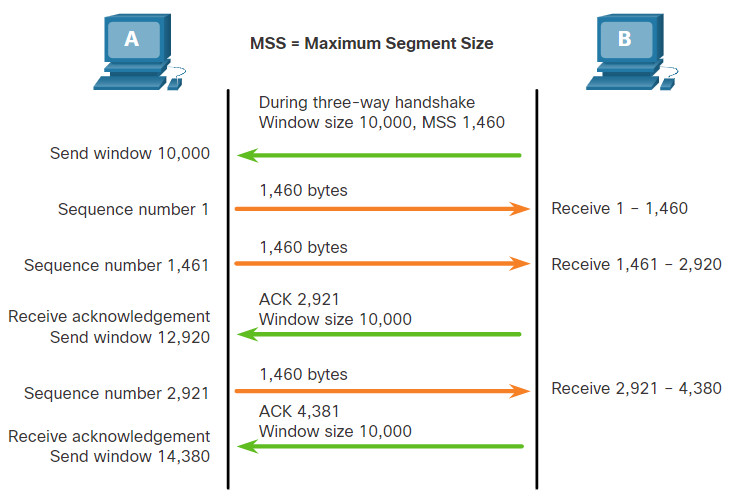

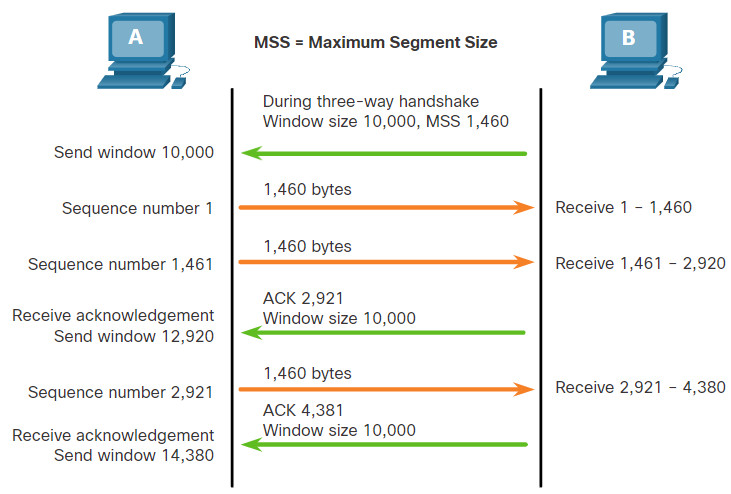

The figure shows an example of window size and acknowledgments.

TCP Window Size Example

The window size determines the number of bytes that can be sent before expecting an acknowledgment. The acknowledgment number is the number of the next expected byte.

The window size is the number of bytes that the destination device of a TCP session can accept and process at one time. In this example, the PC B initial window size for the TCP session is 10,000 bytes. Starting with the first byte, byte number 1, the last byte PC A can send without receiving an acknowledgment is byte 10,000. This is known as the send window of PC A. The window size is included in every TCP segment so the destination can modify the window size at any time depending on buffer availability.

The initial window size is agreed upon when the TCP session is established during the three-way handshake. The source device must limit the number of bytes sent to the destination device based on the window size of the destination. Only after the source device receives an acknowledgment that the bytes have been received, can it continue sending more data for the session. Typically, the destination will not wait for all the bytes for its window size to be received before replying with an acknowledgment. As the bytes are received and processed, the destination will send acknowledgments to inform the source that it can continue to send additional bytes.

For example, it is typical that PC B would not wait until all 10,000 bytes have been received before sending an acknowledgment. This means PC A can adjust its send window as it receives acknowledgments from PC B. As shown in the figure, when PC A receives an acknowledgment with the acknowledgment number 2,921, which is the next expected byte. The PC A send window will increment 2,920 bytes. This changes the send window from 10,000 bytes to 12,920. PC A can now continue to send up to another 10,000 bytes to PC B as long as it does not send more than its new send window at 12,920.

A destination sending acknowledgments as it processes bytes received, and the continual adjustment of the source send window, is known as sliding windows. In the previous example, the send window of PC A increments or slides over another 2,921 bytes from 10,000 to 12,920.

If the availability of the destination’s buffer space decreases, it may reduce its window size to inform the source to reduce the number of bytes it should send without receiving an acknowledgment.

Note: Devices today use the sliding windows protocol. The receiver typically sends an acknowledgment after every two segments it receives. The number of segments received before being acknowledged may vary. The advantage of sliding windows is that it allows the sender to continuously transmit segments, as long as the receiver is acknowledging previous segments. The details of sliding windows are beyond the scope of this course.

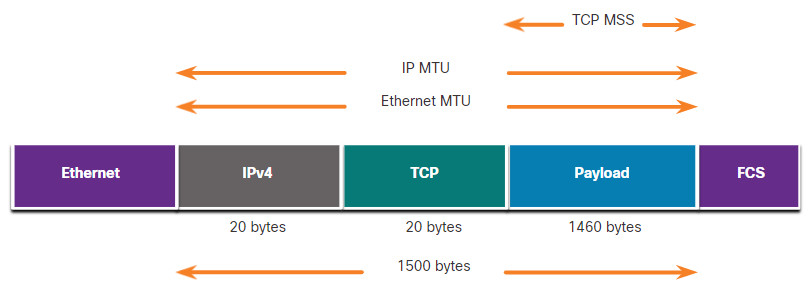

9.3.6 TCP Flow Control – Maximum Segment Size (MSS)

In the figure, the source is transmitting 1,460 bytes of data within each TCP segment. This is typically the Maximum Segment Size (MSS) that the destination device can receive. The MSS is part of the options field in the TCP header that specifies the largest amount of data, in bytes, that a device can receive in a single TCP segment. The MSS size does not include the TCP header. The MSS is typically included during the three-way handshake.

A common MSS is 1,460 bytes when using IPv4. A host determines the value of its MSS field by subtracting the IP and TCP headers from the Ethernet maximum transmission unit (MTU). On an Ethernet interface, the default MTU is 1500 bytes. Subtracting the IPv4 header of 20 bytes and the TCP header of 20 bytes, the default MSS size will be 1460 bytes, as shown in the figure.

9.3.7 TCP Flow Control – Congestion Avoidance

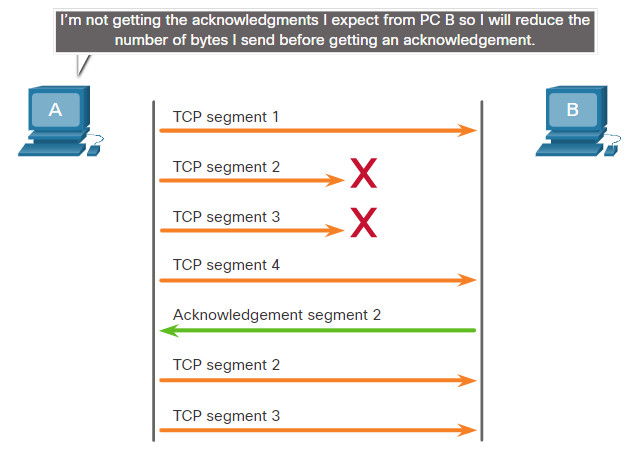

When congestion occurs on a network, it results in packets being discarded by the overloaded router. When packets containing TCP segments do not reach their destination, they are left unacknowledged. By determining the rate at which TCP segments are sent but not acknowledged, the source can assume a certain level of network congestion.

Whenever there is congestion, retransmission of lost TCP segments from the source will occur. If the retransmission is not properly controlled, the additional retransmission of the TCP segments can make the congestion even worse. Not only are new packets with TCP segments introduced into the network, but the feedback effect of the retransmitted TCP segments that were lost will also add to the congestion. To avoid and control congestion, TCP employs several congestion handling mechanisms, timers, and algorithms.

If the source determines that the TCP segments are either not being acknowledged or not acknowledged in a timely manner, then it can reduce the number of bytes it sends before receiving an acknowledgment. As illustrated in the figure, PC A senses there is congestion and therefore, reduces the number of bytes it sends before receiving an acknowledgment from PC B.

TCP Congestion Control

Acknowledgment numbers are for the next expected byte and not for a segment. The segment numbers used are simplified for illustration purposes.

Notice that it is the source that is reducing the number of unacknowledged bytes it sends and not the window size determined by the destination.

Note: Explanations of actual congestion handling mechanisms, timers, and algorithms are beyond the scope of this course.

9.3.8 Lab – Exploring Nmap

Port scanning is usually part of a reconnaissance attack. There are a variety of port scanning methods that can be used. We will explore how to use the Nmap utility. Nmap is a powerful network utility that is used for network discovery and security auditing.

9.4 The Transport Layer Summary

9.4.1 What Did I Learn in this Module?

Transport Layer Characteristics

The transport layer is the link between the application layer and the lower layers of the OSI model that are responsible for network transmission. The transport layer is responsible for logical communications between applications running on different hosts. The transport layer includes TCP and UDP. Transport layer protocols specify how to transfer messages between hosts and is responsible for managing reliability requirements of a conversation. The transport layer is responsible for tracking conversations (sessions), segmenting data and reassembling segments, adding segment header information, identifying applications, and conversation multiplexing. TCP is stateful and reliable. It acknowledges data, resends lost data, and delivers data in sequenced order. TCP is used for email and the web. UDP is stateless and fast. It has low overhead, does not requires acknowledgments, does not resend lost data, and processes data in the order in which it arrives. UDP is used for VoIP and DNS.

The TCP and UDP transport layer protocols use port numbers to manage multiple simultaneous conversations. This is why the TCP and UDP header fields identify a source and destination application port number. The source and destination ports are placed within the segment. The segments are then encapsulated within an IP packet. The combination of the source IP address and source port number, or the destination IP address and destination port number are known as a sockets. The socket is used to identify the server and service being requested by the client and the host and application on the host that should handle the returning data. The range of port numbers is from 0 through 65535.

Transport Layer Session Establishment

The three-way handshake establishes that the destination device is present on the network. It verifies that the destination device has an active service that is accepting requests on the destination port number that the initiating client intends to use. It also informs the destination device that the source client intends to establish a communication session on that port number. The six control bits flags are: URG, ACK, PSH, RST, SYN, and FIN and are used to identify the function of TCP messages that are sent. A client or server can terminate a single conversation supported by TCP by sending a sequence of TCP messages.

Transport Layer Reliability

For the original message to be understood by the recipient, all the data must be received and the data in these segments must be reassembled into the original order. Sequence numbers are assigned in the header of each packet. No matter how well designed a network is, data loss occasionally occurs. TCP provides ways to manage segment losses. There is a mechanism to retransmit segments for unacknowledged data. Host operating systems today typically employ an optional TCP feature called selective acknowledgment (SACK), which is negotiated during the three-way handshake. If both hosts support SACK, the receiver can explicitly acknowledge which segments (bytes) were received including any discontinuous segments. The sending host would therefore only need to retransmit the missing data. Flow control helps maintain the reliability of TCP transmission by adjusting the rate of data flow between source and destination. To accomplish this, the TCP header includes a 16-bit field called the window size. The process of the destination sending acknowledgments as it processes bytes received and the continual adjustment of the source’s send window is known as sliding windows. A source might be transmitting 1,460 bytes of data within each TCP segment. This is the typical maximum segment size (MSS) that a destination device can receive. To avoid and control congestion, TCP employs several congestion handling mechanisms.