14.0 – Introduction

14.0.1 – Welcome

14.0.1.1 – Chapter 14: The IT Professional

An IT professional must be familiar with the legal and ethical issues that are inherent in this industry. There are privacy and confidentiality concerns that you must take into consideration during every customer encounter as you interact with customers in the field, in the office, or over the phone. If you become a bench technician, although you might not interact with customers directly, you will have access to their private and confidential data. This chapter discusses some common legal and ethical issues.

Call center technicians work exclusively over the phone with customers. This chapter covers general call center procedures and the process of working with customers.

As an IT professional, you will troubleshoot and fix computers, and you will frequently communicate with customers and co-workers. In fact, troubleshooting is as much about communicating with the customer as it is about knowing how to fix a computer. In this chapter, you learn to use good communication skills as confidently as you use a screwdriver.

You will also learn about scripting to automate processes and tasks on various operating systems. For example, a script file might be used to automate the process of performing a backup of a customer’s data or run a list of standard diagnostics on a broken computer. The script file can save the technician a lot of time, especially when the same tasks need to be performed on many different computers. You will learn about scripting languages and some basic Windows and Linux script commands. You will also learn key scripting terms like conditional variables, conditional statements, and loops. You will perform a lab writing very basic scripts.

14.1 – Communication Skills and the IT Professional

14.1.1 – Communication Skills, Troubleshooting, and Professional Behavior

14.1.1.1 – Relationship Between Communication Skills and Troubleshooting

Think of a time when you had to call a repair person to get something fixed. Did it feel like an emergency to you? Perhaps you had a bad experience with a repair person. Are you likely to call that same person to fix a problem again? What could that technician have done differently in their communication with you? Did you have a good experience with a repair person? Did that person listen to you as you explained your problem and then ask you a few questions to get more information? Are you likely to call that person to fix a problem again?

Speaking directly with the customer is usually the first step in resolving the computer problem. To troubleshoot a computer, you need to learn the details of the problem from the customer. Most people who need a computer problem fixed are probably feeling some stress. If you establish a good rapport with the customer, the customer might relax a bit. A relaxed customer is more likely to be able to provide the information that you need to determine the source of the problem and then fix it.

Follow these guidelines to provide great customer service:

- Set and meet expectations, adhere to the agreed upon timeline, and communicate the status with the customer.

- If necessary, offer different repair or replacement options.

- Provide documentation on the services provided.

- Follow up with customers and users after services are rendered to verify their satisfaction.

14.1.1.2 – Lab – Technician Resources

A technician’s good communication skills are an aid in the troubleshooting process. It takes time and experience to develop good communication and troubleshooting skills. As your hardware, software, and OS knowledge increases, your ability to quickly determine a problem and find a solution will improve. The same principle applies to developing communication skills. The more you practice good communication skills, the more effective you will become when working with customers. A knowledgeable technician who uses good communication skills will always be in demand in the job market.

As a technician, you also have access to several communication and research tools. All these resources can be used to help gather information for the troubleshooting process

In this lab, you will use the internet to find resources for a specific computer component. Search online for resources that can help you troubleshoot the component.

14.1.1.2 – Lab – Technician Resources

14.1.1.3 – Relationship Between Communication Skills and Professional Behavior

Whether you are talking with a customer on the phone or in person, it is important to communicate well and to present yourself professionally.

Relationship Between Communication Skills and Professional Behavior

If you are talking with a customer in person, that customer can see your body language. If you are talking with a customer over the phone, that customer can hear your tone and inflection. Customers can also sense whether you are smiling when you are speaking with them on the phone. Many call center technicians use a mirror at their desk to monitor their facial expressions.

Successful technicians control their own reactions and emotions from one customer call to the next. A good rule for all technicians to follow is that a new customer call means a fresh start. Never carry your frustration from one call to the next.

14.1.2 – Working with a Customer

14.1.2.1 – Know, Relate, and Understand

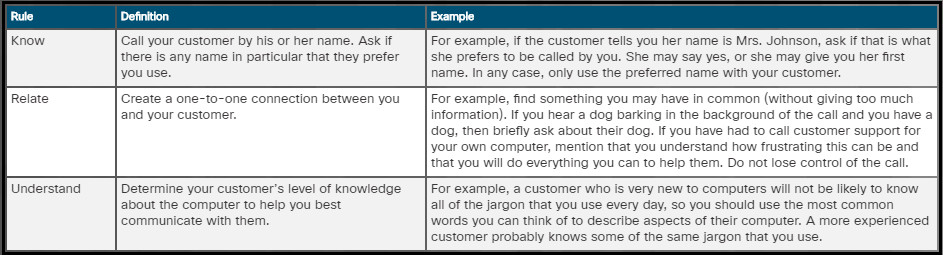

Know, Relate, and Understand

14.1.2.2 – Active Listening

To better enable you to determine the customer’s problem, practice active listening skills. Allow the customer to tell the whole story. During the time that the customer is explaining the problem, occasionally interject some small word or phrase, such as “I understand,” “Yes,” “I see,” or “Okay.” This behavior lets the customer know that you are there and that you are listening.

However, a technician should not interrupt the customer to ask a question or make a statement. This is rude, disrespectful, and creates tension. Many times in a conversation, you might find yourself thinking of what to say before the other person finishes talking. When you do this, you are not actively listening. Instead, listen carefully when your customers speak, and let them finish their thoughts.

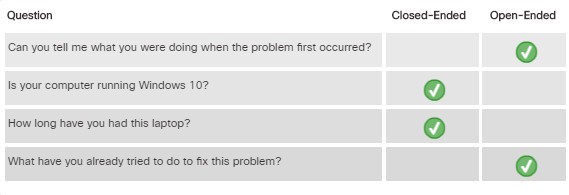

You asked the customer to explain the problem to you. This is known as an open-ended question. An open-ended question rarely has a simple answer. Usually it involves information about what the customer was doing, what they were trying to do, and why they are frustrated.

Active Listening

After you have listened to the customer explain the whole problem, summarize what the customer has said. This helps convince the customer that you have heard and understand the situation. A good practice for clarification is to paraphrase the customer’s explanation by beginning with the words, “Let me see if I understand what you have told me.” This is a very effective tool that demonstrates to the customer that you have listened and that you understand.

After you have assured the customer that you understand the problem, you will probably have to ask some follow-up questions. Make sure that these questions are pertinent. Do not ask questions that the customer has already answered while describing the problem. Doing this only irritates the customer and shows that you were not listening.

Follow-up questions should be targeted, closed-ended questions based on the information that you have already gathered. Closed-ended questions should focus on obtaining specific information. The customer should be able to answer a closed-ended question with a simple “yes” or “no” or with a factual response, such as “Windows 10.”

Use all the information that you have gathered from the customer to complete a work order.

14.1.2.3 – Check Your Understanding – Closed-Ended and Open-Ended Questions

14.1.2.3 – Check Your Understanding – Closed-Ended and Open-Ended Questions

14.1.2.4 – Video Demonstration – Active Listening and Summarizing

Click Play in the figure to hear a recording. The recording contains an example of a technician not using active listening skills and needlessly interrupting the customer. In the second half of this recording, the technician uses active listening skills and does not interrupt the customer.

Tips for Using Active Listening with a Customer

- Do allow the customer to tell their problem.

- Do occasionally interject some small word or phrase such as “I understand,” “Yes,” “I see,” or “Okay.” to let the customer know that you are listening.

- Do summarize the customer’s problem when they are done so that you both are certain that you understand.

- Do ask clarifying questions.

- Do not interrupt the customer the moment you realize you have a question.

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.3 – Professional Behavior

14.1.3.1 – Using Professional Behavior with the Customer

Be positive when communicating with the customer. Tell the customer what you can do. Do not focus on what you cannot do. Be prepared to explain alternative ways that you can help them, such as emailing information and step-by-step instructions, or using remote control software to solve the problem.

Using Professional Behavior with the Customer

When dealing with customers, it is sometimes easier to explain what you should not do. The following list describes things that you should not do when talking with a customer:

- Do not minimize a customer’s problems.

- Do not use jargon, abbreviations, acronyms, and slang.

- Do not use a negative attitude or tone of voice.

- Do not argue with customers or become defensive.

- Do not say culturally insensitive remarks.

- Do not disclose any experiences with customers on social media.

- Do not be judgmental or insulting or call the customer names.

- Avoid distractions and do not interrupt when talking with customers.

- Do not take personal calls when talking with customers.

- Do not talk to co-workers about unrelated subjects when talking with the customer.

- Avoid unnecessary holds and abrupt holds.

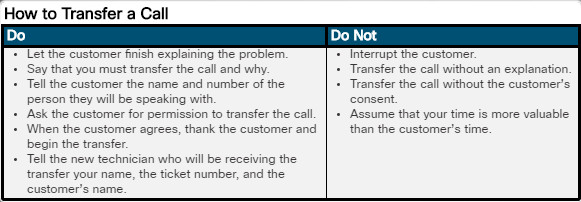

- Do not transfer a call without explaining the purpose of the transfer and getting customer consent.

- Do not use negative remarks about other technicians to the customer.

If a technician is not going to be on time, then the customer should be informed as soon as possible

14.1.3.2 – Tips for Hold and Transfer

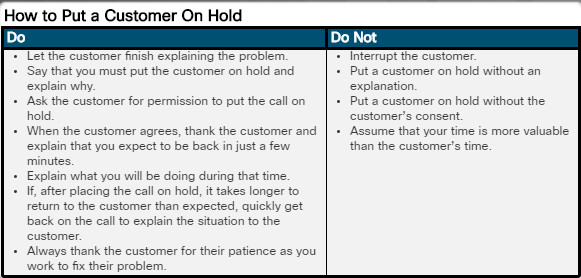

When dealing with customers, it is necessary to be professional in all aspects of your role. You must handle customers with respect and prompt attention. When on a telephone, make sure that you know how to place a customer on hold, as well as how to transfer a customer without losing the call.

How to Put a Customer On Hold

How to Transfer a Call

14.1.3.3 – Video Demonstration – Hold and Transfer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of how to place a customer on hold, as well as how to transfer a customer.

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.3.4 – What Do You Already Know? – Netiquette

14.1.4 – The Customer Call

14.1.4.1 – Keeping the Customer Call Focused

Keeping the Customer Call Focused

Part of your job is to focus the customer during the phone call. When you focus the customer on the problem, it allows you to control the call. These practices make the best use of your time and the customer’s time:

- Use proper language – Be clear and avoid technical language that the customer might not understand.

- Listen and question – Listen carefully to the customer and let them speak. Use open and closed ended questions to learn details about the customer’s problem.

- Give feedback – Let the customer know that you understand the problem and develop a friendly and positive conversational manner.

Just as there are many different computer problems, there are many different types of customers. By using active listening skills, you may be given some hints as to what type of customer is on the phone with you. Is this person very new to computers? Is the person very knowledgeable about computers? Is your customer angry? Do not take any comments personally, and do not retaliate with any comments or criticism. If you stay calm with the customer, finding a solution to the problem will remain the focal point of the call. Recognizing certain customer traits can help you manage the call accordingly.

The videos on the following pages will demonstrate strategies for dealing with different types of difficult customers. The list is not comprehensive, and often, a customer will display a combination of traits. Each video contains a recording of a technician handling a difficult customer type incorrectly, followed by a recording of the same technician handling the customer professionally. A quiz is embedded at the end of each example.

14.1.4.2 – Video Demonstration – The Talkative Customer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of inappropriate and appropriate IT professional behavior with a talkative customer.

Tips for helping a talkative customer

- Do allow the customer to talk for about one minute.

- Do gather as much information about the problem as possible.

- Do politely step in to refocus the customer. This is the one exception to the rule of never interrupting a customer.

- Do ask as many closed-ended questions as you need to after you have regained control of the call.

- Do not encourage non-problem related conversation by asking social questions such as “How are you today?”

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.4.3 – Video Demonstration – The Rude Customer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of inappropriate and appropriate IT professional behavior with a rude customer.

Tips for helping a rude customer

- Do listen very carefully, as you do not want to ask the customer to repeat any information.

- Do follow a step-by-step approach to determining and solving the problem.

- Do try to contact the customer’s favorite technician, if they have one, to see if that technician can take the call. Tell the customer, “I can help you right now, or see if your preferred technician is available.” If the customer wants the preferred technician and they are available, politely transfer the call. If the technician is not available, ask the customer if he or she will wait. If they will wait, note that in the ticket.

- Do apologize for the wait time and the inconvenience, even if there has been no wait time.

- Do reiterate that you want to solve their problem as quickly as possible.

- Do not ask the customer to do any obvious steps if there is any way you can determine the problem without that information.

- Do not be rude to the customer, even if they are rude to you.

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.4.4 – Video Demonstration – The Knowledgeable Customer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of inappropriate and appropriate IT professional behavior with a knowledgeable customer.

Tips for helping a knowledgeable customer

- Do consider setting up a call with a level two technician, if you are a level one technician.

- Do give the customer the overall approach to what you are trying to verify.

- Do not follow a step-by-step process with this customer.

- Do not ask to check the obvious, such as the power cord or the power switch. Consider suggesting a reboot instead

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.4.5 – Video Demonstration – The Angry Customer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of inappropriate and appropriate IT professional behavior with a talkative customer.

Tips for helping a talkative customer

- Do let the customer tell their problem without interrupting, even if they are angry. This allows the customer to release some of their anger before you proceed.

- Do sympathize with the customer’s problem.

- Do apologize for the wait time or inconvenience.

- Do not, if at all possible, put this customer on hold or transfer the call.

- Do not spend the call time talking about what caused the problem. It is better to redirect the conversation to solving the problem.

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.1.4.6 – Video Demonstration – The Inexperienced Customer

Click Play in the figure to view a demonstration of inappropriate and appropriate IT professional behavior with an inexperienced customer.

Tips for helping an inexperienced customer

- Do allow the customer to talk for about one minute.

- Do gather as much information about the problem as possible.

- Do politely step in to refocus the customer. This is the one exception to the rule of never interrupting a customer.

- Do ask as many closed-ended questions as you need to after you have regained control of the call.

- Do not encourage non-problem related conversation by asking social questions such as “How are you today?”

Click here to read the transcript of this video.

14.2 – Operational Procedures

14.2.1 – Documentation

14.2.1.1 – Documentation Overview

Documentation Overview

Different types of organizations have different operating procedures and processes that govern business functions. Documentation is the main way of communicating these processes and procedures to employees, customers, suppliers, and others.

Purposes for documentation include:

- Providing descriptions for how products, software, and hardware function through the use of diagrams, descriptions, manual pages and knowledgebase articles.

- Standardizing procedures and practices so that they can be repeated accurately in the future.

- Establishing rules and restrictions on the use of the organization’s assets including acceptable use policies for internet, network, and computer usage.

- Reducing confusion and mistakes saving time and resources.

- Complying with governmental or industry regulations.

- Training new employees or customers.

Keeping documentation up to date is just as important as creating it. Updates to policies and procedures are inevitable, especially in the constantly changing environment of information technology. Establishing a standard timeframe for reviewing documents, diagrams, and compliance policies ensures that the correct information is available when it is needed.

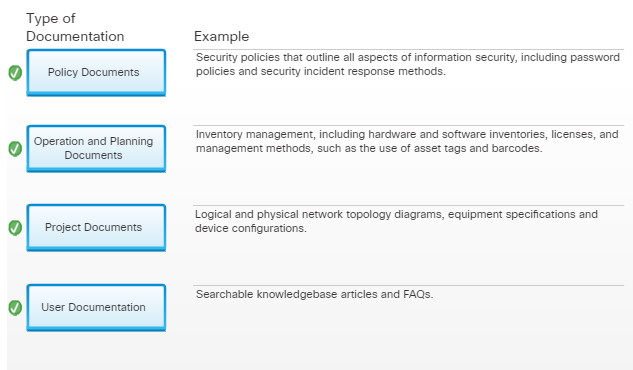

14.2.1.2 – IT Department Documentation

Keeping documentation current is a challenge for even the best managed IT departments. IT documentation can come in many different forms, including diagrams, manuals, configurations and source code. In general, IT documentation falls into four broad categories: Policies, Operations, Projects and User Documentation. Click each category in the figure for more information.

14.2.1.3 – Regulatory Compliance Requirements

Federal, state, local, and industry regulations can have documentation requirements over and above what is normally documented in the company’s records. Regulatory and compliance policies often specify what data must be collected and how long it must be retained. A few of the regulations may have implications on internal company processes and procedures. Some regulations require keeping extensive records regarding how the data is accessed and used.

Regulatory and Compliance Policy

Failure to comply with laws and regulations can have severe consequences, including fines, termination of employment, and even incarceration of offenders. It is important to know how laws and regulations apply to your organization and to the work you perform.

14.2.1.4 – Check Your Understanding – Documentation

14.2.1.4 – Check Your Understanding – Documentation

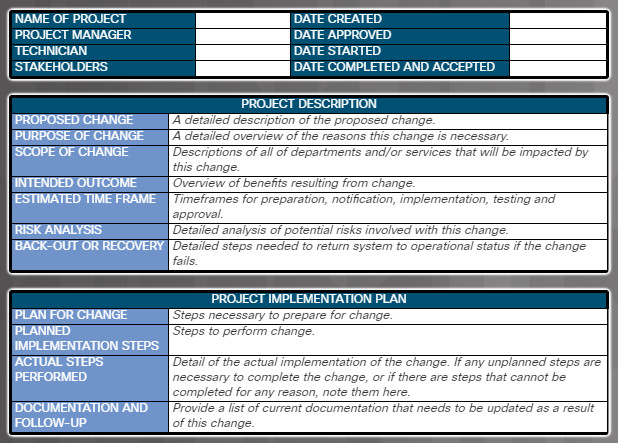

14.2.2.1 – Change Control Process

Controlling changes in an IT environment can be difficult. Changes can be as minor as replacing a printer, or as important as upgrading all the enterprise servers to the latest operating system version. Most larger enterprises and organizations have change management procedures in place to ensure that installations and upgrades go smoothly,

A good change management process can prevent business functions from being negatively impacted by the updates, upgrades, replacements, and reconfigurations that are a normally part of IT operations. Change management usually starts with a change request from a stakeholder or from within the IT organization itself. Most change management processes include the following:

- Identification – What is the change? Why is it needed? Who are the stakeholders?

- Assessment – What business processes are impacted by this change? What are the costs and resources necessary for implementation? What risks are associated with making (or not making) this change?

- Planning – How long will this change take to implement? Is there downtime involved? What is the roll back or recovery process if the change fails?

- Approval – Who must authorize this change? Has approval to proceed with the change been obtained?

- Implementation – How are stakeholders notified? What are the steps to complete the change, and how will the results be tested?

- Acceptance – What is the acceptance criteria and who is responsible for accepting the results of the change?

- Documentation – What updates are required to change logs, implementation steps, or IT documents because of this change?

CHANGE CONTROL WORKSHEET

All the results of the process are recorded on a change request or change control document that becomes part of the IT documentation. Some expensive or complex changes that impact necessary business functions may require the approval of a change board or committee before work can begin.

Click here to view an example of a Change Control Worksheet.

14.2.3 – Disaster Prevention and Recovery

14.2.3.1 – Disaster Recovery Overview

We often think of a disaster as being something catastrophic, such as the destruction caused by an earthquake, tsunami or wildfire. In information technology, a disaster can include anything from natural disasters that affect the network structure to malicious attacks on the network itself. The impact of data loss or corruption from unplanned outages caused by hardware failure, human error, hacking, or malware can be significant.

A disaster recovery plan is a comprehensive document that describes how to restore operation quickly and keep critical IT functions running during or after a disaster occurs. The disaster recovery plan can include information such as offsite locations where services can be moved, information on replacing network devices and servers, and backup connectivity options.

Disaster Recovery Overview

Some services may even need to be available during the disaster in order to provide information to IT personnel and updates to others in the organization. Services that might need to be available during or immediately after a disaster include:

- Web services and internet connectivity.

- Data stores and backup files.

- Directory and authentication services.

- Database and application servers.

- Telephone, email and other communication services.

In addition to having a disaster recovery plan, most organizations take steps to ensure they are ready in case a disaster occurs. These preventive measures can ease the impact of unplanned outages on the operation of the organization.

14.2.3.2 – Preventing Downtime and Data Loss

Preventing Downtime and Data Loss

Some business applications cannot tolerate any downtime. They use multiple data centers capable of handling all data processing needs, which run in parallel with data mirrored or synchronized between the centers. Often, these businesses run their applications from cloud servers to minimize the impact of physical damage to their sites.

Data and Operating System Backup

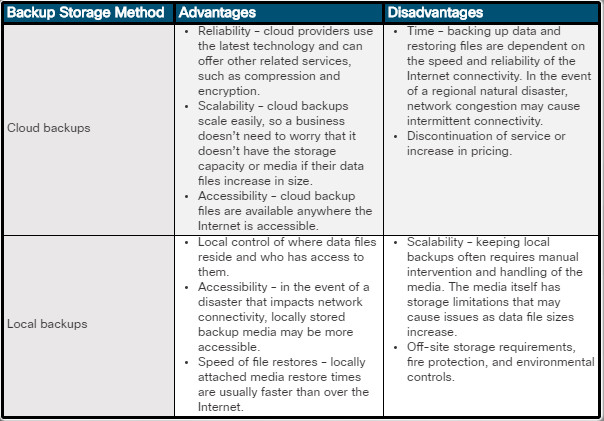

Even the best disaster recovery procedures cannot restore services quickly if there are no current backups of data and operating system environments. It is much easier to restore data from a reliable backup than it would be to recreate it. There are generally two types of backup done for disaster recovery purposes: image backups and file backups. Image backups record all the information stored on the computer at the time the image is created while file backups store only the specific files indicated at the time the backup is run no matter which type of backup is made, it is critical that the restore process is tested frequently to ensure that it will function when it is needed.

Backup files need to be available to the people who will be responsible for restoring and recovering the systems after an unplanned outage. Backup media can be stored securely off-site or backup files can be stored in an online location, such as a cloud service provider. Locally stored files may be accessible if communication service outages prevent accessing the Internet. Backup files stored online have the benefit of being accessible from anywhere the Internet is available.

Power and Environment Controls

Keeping the power on for a data center or for critical communications infrastructure can prevent data loss caused by interruptions or spikes in the electrical power delivery. Sometimes even minor natural disasters can cause power outages that last for longer than 24 hours. Small surge protectors and uninterrupted power supplies (UPS) can prevent damage from minor power problems, but for larger outages, a generator might be required. Data centers require power not only for the computing equipment but also for air conditioning and fire suppression. Large UPS units can keep a data center operational until a fuel-powered generator comes online.

14.2.3.3 – Elements of a Disaster Recovery Plan

Elements of a Disaster Recovery Plan

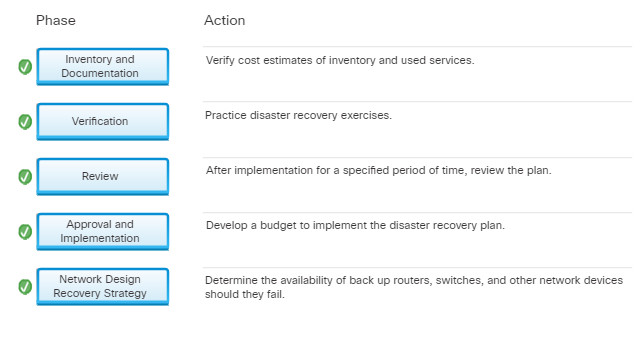

The first step in creating a disaster recovery plan is to identify the most critical services and applications that will need to be restored quickly. That information should be used to create a disaster recovery plan. There are five major phases of creating and implementing a disaster recovery plan:

Phase 1 – Network Design Recovery Strategy

Analyze the network design. Some aspects of the network design that should be included in the disaster recovery are:

- Is the network designed to survive a major disaster? Are there backup connectivity options and is there redundancy in the network design?

- Availability of offsite servers or cloud providers that can support applications such as email and database services.

- Availability of backup routers, switches, and other network devices.

- Location of services and resources that the network needs. Are they spread over a wide geography? Are backups easily accessible in an emergency?

Phase 2 – Inventory and Documentation

Create an inventory of all locations, devices, vendors, used services, and contact names. Verify cost estimates that are created in the risk assessment step.

Phase 3 – Verification

Create a verification process to prove that the disaster recovery strategy works. Practice disaster recovery exercises to ensure that the plan is up to date and workable.

Phase 4 – Approval and Implementation

Obtain senior management approval and develop a budget to implement and maintain the disaster recovery plan.

Phase 5 – Review

After the disaster recovery plan has been implemented for a year, review the plan. Information in the plan must be kept up to date, or critical services may not be restored in the case of a disaster.

14.2.3.4 – Check Your Understanding – Disaster Recovery

14.2.3.4 – Check Your Understanding – Disaster Recovery

14.3 – Ethical and Legal Considerations

14.3.1 – Ethical and Legal Considerations in the IT Profession

14.3.1.1 – Ethical and Legal Considerations in IT

Ethical and Legal Considerations in IT

When you are working with customers and their equipment, there are some general ethical customs and legal rules that you should observe. These customs and rules often overlap.

You should always have respect for your customers, as well as for their property. Computers and monitors are property, but property also includes any information or data that might be accessible, for example:

- Emails

- Phone lists and contact lists

- Records or data on the computer

- Hard copies of files, information, or data left on a desk

Before accessing computer accounts, including the administrator account, get the permission of the customer. During the troubleshooting process, you might have gathered some private information, such as usernames and passwords. If you document this type of private information, you must keep it confidential. Divulging customer information to anyone else is not only unethical but might be illegal. Do not send unsolicited messages to a customer. Do not send unsolicited mass mailings or chain letters to customers. Never send forged or anonymous emails. Legal details of customer information are usually covered under the service-level agreement (SLA). The SLA is a contract between a customer and a service provider that defines the service or goods the customer will receive and the standards to which the provider must comply.

14.3.1.2 – Personal Identifiable Information (PII)

Take particular care to keep personally identifiable information (PII) confidential. PII is any data that could potentially identify a specific individual. NIST Special Publication 800-122 defines PII as, “any information about an individual maintained by an agency, including (1) any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual‘s identity, such as name, social security number, date and place of birth, mother‘s maiden name, or biometric records; and (2) any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information”.

Personal Identifiable Information (PII)

Examples of PII include, but are not limited to:

- Names, such as full name, maiden name, mother‘s maiden name, or alias

- Personal identification numbers, such as social security number (SSN), passport number, driver‘s license number, taxpayer identification number, or financial account or credit card number, address information, such as street address or email address

- Personal characteristics, including photographic images (especially of the face or other identifying characteristics), fingerprints, handwriting, or other biometric data (e.g., retina scan, voice signature, facial geometry)

PII violations are regulated by several organizations in the United States, depending on the type of data. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) also regulates how data is handled for personal data, including financial and healthcare information. To learn more about GDPR visit www.eugdpr.org.

14.3.1.3 – Payment Card Industry (PCI)

Payment Card Industry (PCI) information is considered personal information that needs to be protected. We hear about countless breaches of credit card information on the news that impact millions of users. Often it is days or weeks before a merchant realizes there is a breach. All businesses and organizations, large or small, need to adhere to strict standards to protect the consumer’s information.

Payment Card Industry (PCI)

The PCI Security Standards Council was formed in 2005 by the 5 major credit card companies in an effort to protect account numbers, expiration dates, magnetic strip and chip data for transactions around the globe. The PCI council partners with organizations, including NIST, to develop standards and security procedures around these transactions.

In one of the worst breaches in history, malware infected the point of sale system of a major retailer, impacting millions of consumers. This may have been prevented with adequate software and policies for data breach prevention. As an IT professional you should be aware of PCI compliance standards.

For more information on PCI, visit www.pcisecuritystandards.org.

14.3.1.4 – Protected Health Information (PHI)

Protected Health Information (PHI) is another form of PII that needs to be secured and protected. PHI includes patient names, addresses, dates of visits, telephone and fax numbers, and email addresses. With the move from paper copy records to electronic records, Electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) is also regulated. Penalties for breaches of PHI and ePHI are very severe and regulated by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Protected Health Information (PHI)

Examples of these types of breaches are easily found with an internet search. Unfortunately, the breach may be undetected for months. Some breaches have occurred from one person giving out information to an unauthorized person. Human error can cause violations. For example, accidentally faxing health information to the wrong party is a violation. Other examples are sophisticated attacks. Recent phishing attacks on a California-based health plan went undetected for almost a month before they recognized it and then notified 37,000 patients that their data had been breached. As an IT professional, you should be aware of protecting PHI and ePHI.

For more information about PHI and ePHI, visit www.hhs.gov and search for PHI.

Search the internet for the regulatory agencies in your state, country, or province.

14.3.1.5 – Lab – Investigate Breaches of PII, PHI, PCI

In this lab, you will investigate breaches of PII, PHI and PCI.

14.3.1.5 – Lab – Investigate Breaches of PII, PHI, PCI

14.3.1.6 – Legal Considerations in IT

Legal Considerations in IT

The laws in different countries and legal jurisdictions vary, but generally, actions such as the following are considered to be illegal:

- It is not permissible to make any changes to system software or hardware configurations without customer permission.

- It is not permissible to access a customer’s or co-worker’s accounts, private files, or email messages without permission.

- It is not permissible to install, copy, or share digital content (including software, music, text, images, and video) in violation of copyright and software agreements or the applicable law. Copyright and trademark laws vary between states, countries, and regions.

- It is not permissible to use a customer’s company IT resources for commercial purposes.

- It is not permissible to make a customer’s IT resources available to unauthorized users.

- It is not permissible to knowingly use a customer’s company resources for illegal activities. Criminal or illegal use typically includes obscenity, child pornography, threats, harassment, copyright infringement, Internet piracy, university trademark infringement, defamation, theft, identity theft, and unauthorized access.

It is not permissible to share sensitive customer information. You are required to maintain the confidentiality of this data.

This list is not exhaustive. All businesses and their employees must know and comply with all applicable laws of the jurisdiction in which they operate.

14.3.1.7 – Licensing

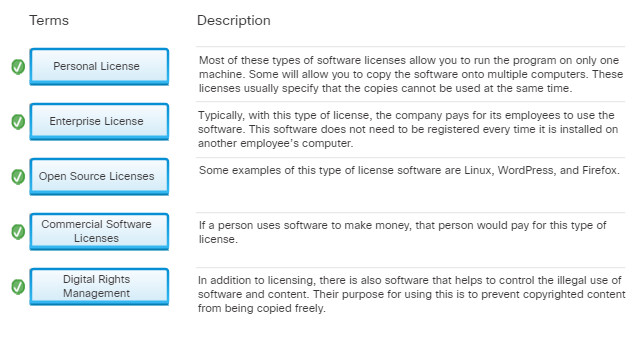

Licensing

- Licensing

As an IT technician, you may encounter customers who are using software illegally. It is important that you understand the purpose and types of common software licenses, should you determine that a crime has been committed. Your responsibilities are usually covered in your company’s corporate end-user policy. In all instances, you must follow security best practices, including documentation and chain of custody procedures.

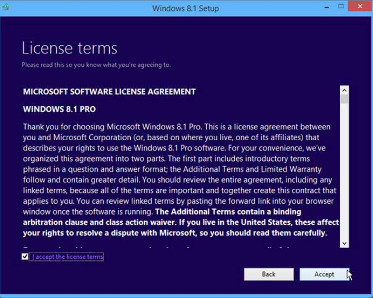

A software license is a contract that outlines the legal use, or redistribution, of that software. Most software licenses grant end-user permission to use one or more copies of software. They also specify the end-user’s rights and restrictions. This ensures that the software owner’s copyright is maintained. It is illegal to use licensed software without the appropriate license. - Personal License

Most software is licensed rather than sold. Some types of personal software licenses regulate how many computers can run a copy of the software. Other licenses specify the number of users that can access the software. Most personal software licenses allow you to run the program on only one machine. There are personal software licenses that allow you to copy the software onto multiple computers. These licenses usually specify that the copies cannot be used at the same time.

One example of a personal software license is an End User License Agreement (EULA). A EULA is a license between the software owner and an individual end-user. The end-user must agree to accept the terms of the EULA. Sometimes, accepting a EULA is as simple as opening the physical package that holds a CD of the software, or by downloading and installing the software. A common example of agreeing to a EULA occurs when updating the software on tablets and smartphones. The end-user must agree to accept the EULA when updating the operating system, or installing or updating software found on the device, by clicking “I accept the license terms”, as shown in the figure. - Enterprise License

An enterprise license is a software site license held by a company. Typically with an enterprise license, the company pays for its employees to use the software. This software does not need to be registered every time it is installed on another employee’s computer. In some cases, the employees may need to use a password to activate each copy of the license. - Open Source Licenses

Open source licensing is a copyright license for software that allows developers to modify and share the source code that runs the software. In some cases, an open source license means that the software is free to all users. In other cases, it means that the software can be purchased. In both instances, users have access to the source code. Some examples of open source software are Linux, WordPress, and Firefox.

If software is being used by an individual who is not using it to make money, that person would have a personal license for that software. Personal software licenses are often free or low-cost. - Commercial Software License

If a person uses software to make money, that person would pay a commercial license. Commercial software licenses are usually more expensive than personal licenses. - Digital Rights Management

In addition to licensing, there is also software that helps to control the illegal use of software and content. Digital rights management (DRM) is software that is designed to prevent illegal access to digital content and devices. DRM is used by hardware and software manufacturers, publishers, copyright holders, and individuals. Their purpose for using DRM is to prevent copyrighted content from being copied freely. This helps the copyright holder to maintain control of the content and to be paid for access to that content.

14.3.1.8 – Check Your Understanding – Licensing

14.3.1.8 – Check Your Understanding – Licensing

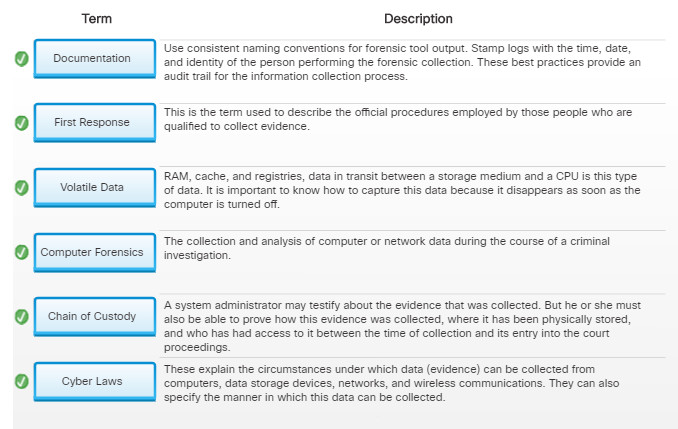

14.3.2.1 – Computer Forensics

Data from computer systems, networks, wireless communications, and storage devices may need to be collected and analyzed in the course of a criminal investigation. The collection and analysis of data for this purpose is called computer forensics. The process of computer forensics encompasses both IT and specific laws to ensure that any data collected is admissible as evidence in court.

Computer Forensics

Depending on the country, illegal computer or network usage may include:

- Identity theft

- Using a computer to sell counterfeit goods

- Using pirated software on a computer or network

- Using a computer or network to create unauthorized copies of copyrighted materials, such as movies, television programs, music, and video games

- Using a computer or network to sell unauthorized copies of copyrighted materials

- Pornography

This is not an exhaustive list. Becoming familiar with the signs of illegal computer or network usage can help you to identify a situation where you suspect illegal activity and report it to the authorities.

14.3.2.2 – Data Collected in Computer Forensics

Data Collected in Computer Forensics

Two basic types of data are collected when conducting computer forensics procedures:

- Persistent data – Persistent data is stored on a local drive, such as an internal or external hard drive, or an optical drive. When the computer is turned off, this data is preserved.

- Volatile data – RAM, cache, and registries contain volatile data. Data in transit between a storage medium and a CPU is also volatile data. If you are reporting illegal activity or are part of an incident response team, it is important to know how to capture this data, because it disappears as soon as the computer is turned off.

14.3.2.3 – Cyber Law

There is no single law known as a cyber law. Cyber law is a term to describe the international, regional, country, and state laws that affect computer security professionals. IT professionals must be aware of cyber law so that they understand their responsibility and their liability as it relates to cybercrimes.

Cyber Law

Cyber laws explain the circumstances under which data (evidence) can be collected from computers, data storage devices, networks, and wireless communications. They can also specify the manner in which this data can be collected. In the United States, cyber law has three primary elements:

- Wiretap Act

- Pen/Trap and Trace Statute

- Stored Electronic Communication Act

IT professionals should be aware of the cyber laws in their country, region, or state.

14.3.2.4 – First Response

First response is the term used to describe the official procedures employed by those people who are qualified to collect evidence. System administrators, like law enforcement officers, are usually the first responders at potential crime scenes. Computer forensics experts are brought in when it is apparent that there has been illegal activity.

First Response

Routine administrative tasks can affect the forensic process. If the forensic process is improperly performed, evidence that has been collected might not be admissible in court.

As a field or a bench technician, you may be the person who discovers illegal computer or network activity. If this happens, do not turn off the computer. Volatile data about the current state of the computer can include programs that are running, network connections that are open, and users who are logged in to the network or to the computer. This data helps to determine a logical timeline of the security incident. It may also help to identify those responsible for the illegal activity. This data could be lost when the computer is powered off.

Be familiar with your company’s policy regarding cybercrimes. Know who to call, what to do and, just as importantly, know what not to do.

14.3.2.5 – Documentation

The documentation required by a system administrator and a computer forensics expert is extremely detailed. They must document not only what evidence was gathered, but how it was gathered and with which tools. Incident documentation should use consistent naming conventions for forensic tool output. Stamp logs with the time, date, and identity of the person performing the forensic collection. Document as much information about the security incident as possible. These best practices provide an audit trail for the information collection process.

Documentation

Even if you are not a system administrator or computer forensics expert, it is a good habit to create detailed documentation of all the work that you do. If you discover illegal activity on a computer or network on which you are working, at a minimum, document the following:

- Initial reason for accessing the computer or network

- Time and date

- Peripherals that are connected to the computer

- All network connections

- Physical area where the computer is located

- Illegal material that you have found

- Illegal activity that you have witnessed (or you suspect has occurred)

- Which procedures you have executed on the computer or network

First responders want to know what you have done and what you have not done. Your documentation may become part of the evidence in the prosecution of a crime. If you make additions or changes to this documentation, it is critical that you inform all interested parties.

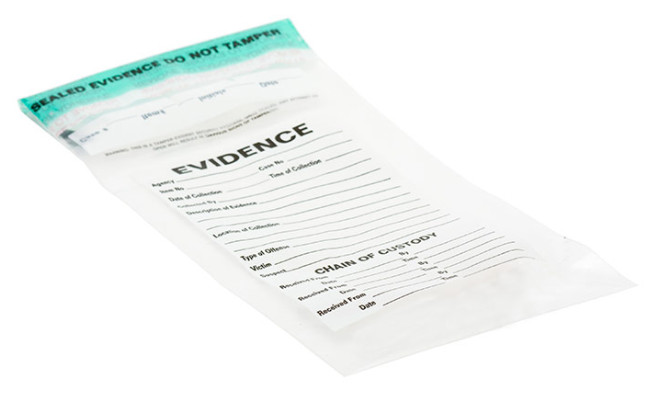

14.3.2.6 – Chain of Custody

For evidence to be admitted, it must be authenticated. A system administrator may testify about the evidence that was collected. But he or she must also be able to prove how this evidence was collected, where it has been physically stored, and who has had access to it between the time of collection and its entry into the court proceedings. This is known as the chain of custody. To prove the chain of custody, first responders have documentation procedures in place that track the collected evidence. These procedures also prevent evidence tampering so that the integrity of the evidence can be ensured.

Chain of Custody

Incorporate computer forensics procedures into your approach to computer and network security to ensure the integrity of the data. These procedures help you capture necessary data in the event of a network breach. Ensuring the viability and integrity of the captured data helps you prosecute the intruder.

14.3.2.7 – Check Your Understanding – Legal Procedures Overview

14.3.2.7 – Check Your Understanding – Legal Procedures Overview

14.4.1.1 – Call Centers

Call centers tend to have a large number of cubicles. Each cubicle has a chair, at least one computer, a phone, and a headset. The technicians working at these cubicles have varied levels of experience with computers, and some specialize in certain types of computers, hardware, software, or operating systems.

Call Centers

All the computers in a call center have support software. The technicians use this software to manage many of their job functions.

- Log and Track Incidents

The software may manage call queues, set call priorities, assign calls, and escalate calls. - Record Contact Information

The software may store, edit, and recall customer names, email addresses, phone numbers, location, websites, fax numbers, and other information in a database. - Research Product Information

The software may provide technicians with information regarding the products supported, including features, limitations, new versions, configuration constraints, known bugs, product availability, links to online help files, and other information. - Run Diagnostic Utilities

The software may have several diagnostic utilities, including remote diagnostic software, in which the technician can take over a customer’s computer while sitting at a desk in the call center. - Research a Knowledge Base

The software may contain a knowledge database that is pre-programmed with common problems and their solutions. This database may grow as technicians add their own records of problems and solutions. - Collect Customer Feedback

The software may collect customer feedback regarding satisfaction with the call center’s products and services.

A call center environment is usually very organized and professional. Customers call in to receive help for a specific computer-related problem. The typical workflow of a call center starts with calls from customers displayed on a callboard. Level one technicians answer these calls in the order that the calls arrive. If the level one technician cannot solve the problem, it is escalated to a level two technician. In all instances, the technician must supply the level of support that is outlined in the customer’s Service Level Agreement (SLA).

A call center might exist within a company and offer service to the employees of that company as well as to the customers of that company’s products. Alternatively, a call center might be an independent business that sells computer support as a service to outside customers. In either case, a call center is a busy, fast-paced work environment, often operating 24 hours a day.

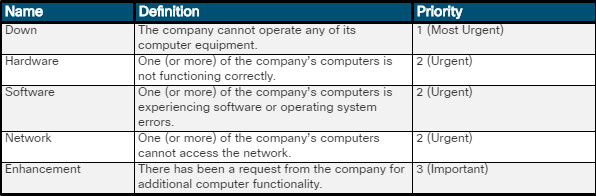

Call Prioritization

Each call center has business policies regarding call priority. Consider this sample chart of how calls can be named, defined, and prioritized.

Call Prioritization

14.4.1.2 – Level One Technician Responsibilities

Call centers sometimes have different names for level one technicians. These technicians might be known as level one analysts, dispatchers, or incident screeners. Regardless of the title, the level one technician’s responsibilities are fairly similar from one call center to the next.

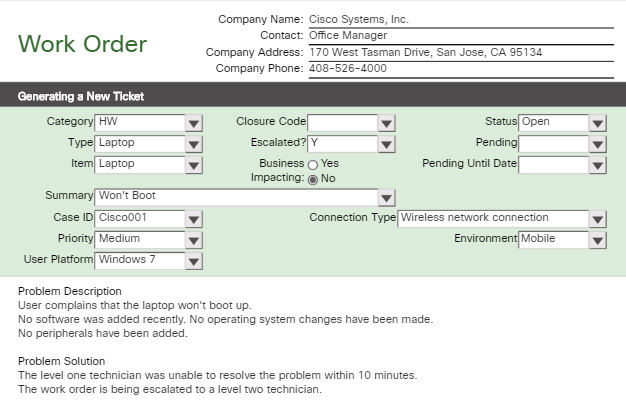

The primary responsibility of a level one technician is to gather pertinent information from the customer. The technician has to accurately enter all information into the ticket or work order. Examples of the type of information that the level one technician must obtain is shown in the figure.

Information Checklist

- Contact information

- What is the manufacturer and model of computer?

- What OS is the computer using?

- Is the computer plugged in to the wall or running on battery power?

- Is the computer on a network? If so, is it a wired or wireless connection?

- Was any specific application being used when the problem occurred?

- Have any new drivers or updates been installed recently? If so, what are they?

- Description of the problem

- Priority of problem

Some problems are very simple to resolve, and a level one technician can usually take care of these without escalating the work order to a level two technician.

When a problem requires the expertise of a level two technician, the level one technician must describe a customer’s problem on a work order using a succinct sentence or two. An accurate description is important because it helps other technicians quickly understand the situation without having to ask the customer the same questions again.

14.4.1.3 – Level Two Technician Responsibilities

As with level one technicians, call centers sometimes have different names for level two technicians. These technicians might be known as product specialists or technical-support personnel. The level two technician’s responsibilities are generally the same from one call center to the next.

The level two technician is usually more knowledgeable and experienced than the level one technician or has been working for the company for a longer period of time. When a problem cannot be resolved within a predetermined amount of time, the level one technician prepares an escalated work order, as shown in the figure. The level two technician receives the escalated work order with the description of the problem and then calls the customer back to ask any additional questions and resolve the problem.

Escalated Work Order

Level two technicians can also use remote access software to connect to the customer’s computer to update drivers and software, access the operating system, check the BIOS, and gather other diagnostic information to solve the problem.

14.4.1.4 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Hardware Problem

In this lab, you will gather data from the customer, and then instruct the customer to fix a computer that does not boot.

14.4.1.4 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Hardware Problem

14.4.1.5 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix an Operating System Problem

In this lab, you will gather data from the customer, and then instruct the customer to fix a computer that does not connect to the network.

14.4.1.5 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix an Operating System Problem

14.4.1.6 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Network Problem

In this lab, you will gather data from the customer, and then instruct the customer to fix a computer that does not connect to the network.

14.4.1.6 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Network Problem

14.4.1.7 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Security Problem

In this lab, you will gather data from the customer and instruct the customer to fix a computer that cannot connect to a workplace wireless network.

14.4.1.7 – Lab – Remote Technician – Fix a Security Problem

14.4.2 – Basic Scripting and the IT Professional

14.4.2.1 – Script Examples

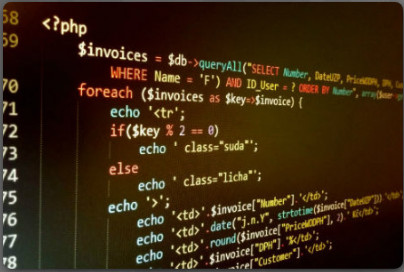

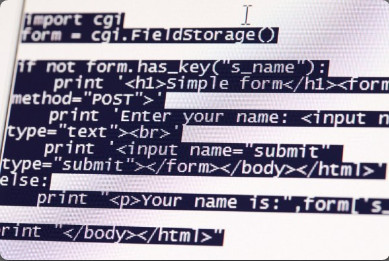

As an IT professional, you will be exposed to many different types of files. One very important type of file is the script file. A script file is a simple text file written in scripting languages to automate processes and tasks on various operating systems. In the field, a script file might be used to automate the process of performing a backup of a customer’s data or run a list of standard diagnostics on a broken computer. The script file can save the technician a lot of time, especially when the same tasks need to be performed on many different computers. You should also be able to identify the many different types of script files because a script file may be causing a problem at startup or during a specific event. Often, preventing the script file from running may eliminate the problem that is occurring.

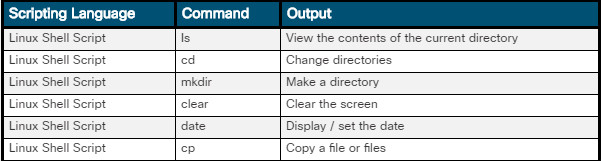

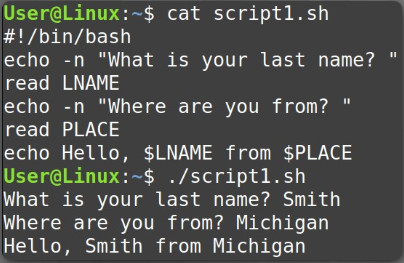

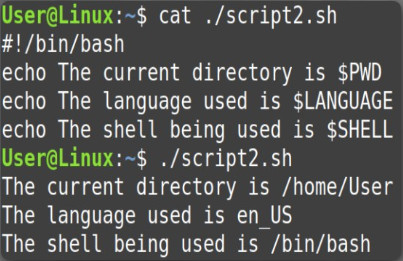

The commands in a script file might be written on the command line one at a time but, is more effectively done in a script file. The script is designed to be executed line by line using a command line interpreter in order to perform various commands. The script can be created using a text editor such as Notepad but, an IDE (Integrated Development Environment) is often used to write and execute the script. Figure 1 is an image of a Windows batch script. Figure 2 is an image of a Linux shell script.

14.4.2.2 – Scripting Languages

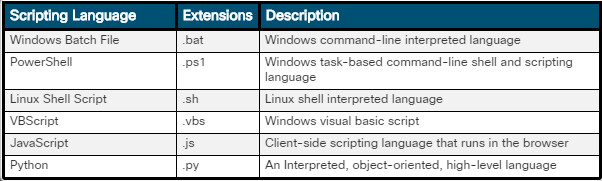

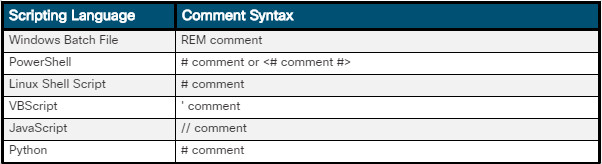

A scripting language is different than a compiled language because each line is interpreted and then executed when the script is run. Examples of scripting languages include Windows batch files, PowerShell, Linux shell script, VBScript, JavaScript, and Python. Compiled languages such as C, C++, C#, and Java, need to be converted into executable code using a “compiler”. Executable code is directly readable by the CPU while scripting languages are interpreted into code that the CPU can read one line at a time by a command interpreter or by the operating system. This makes scripting languages unsuitable for situations where performance is a significant factor. The table in Figure 1 shows a list of scripting languages and their extensions. Figure 2 is a table of various comments found in scripts.

Script Types

Script Syntax

14.4.2.3 – Basic Script Commands

Various commands are available at the terminals of each operating system. Some Windows commands are based on DOS and accessible through the command prompt. Other Windows commands are accessible through PowerShell. Linux commands are written to be compatible with UNIX commands and are often accessed through BASH (Bourne Again SHell). Figure 1 is a table of various DOS commands. Figure 2 is a table of various BASH commands.

14.4.2.4 – Variables / Environmental Variables

Variables are designated places to store information within a computer. A primary function of computers is to manipulate variables. The figure shows a script where a user is prompted for their last name (LNAME) and where they are from (PLACE). The script then shows the execution and output of the script.

Variables

Some variables are environmental, which means that they are used by the operating system to keep track of important details such as: username, home directory, and language. The figure is of a shell script depicting environmental variables. The Linux variables PWD, LANGUAGE, and SHELL were preset when the user logged into this terminal. To view a list of all environmental variables use the env command. Some useful Windows environmental variables are %SystemDrive% (the drive where the system folder is) and %WinDir% (exactly where the Windows folder is).

Environmental Variables

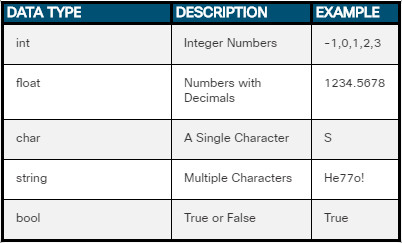

The figure on this page is a table of variable types.

Some scripting languages require that variables are defined as being integers (numbers), characters, strings or something else. In code, a string usually contains multiple characters but can also use numbers and spaces. Often, when defining a string, quotes are used to denote the beginning and end of the string, for example, “Dan sold 3 cars yesterday”

Variable Types

14.4.2.5 – Conditional Statements

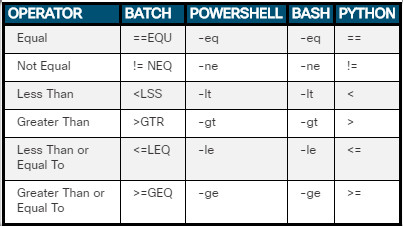

Conditional statements are needed for scripts to make decisions. These statements usually come in the form of an if-else or a case statement. In order for these statements to make a decision, a comparison must be made using operators. The syntax of these commands will vary, depending on the Operator language.

Click each button to learn more.

Conditional Statements

This figure is a list of relational operators in various scripts.

When making a mathematical comparison, use relational operators. Other types of operators include arithmetic (+, -, *, /, %), logical (and, or, not), assignment (+=, -+, *=), and bitwise (&, |, ^).

Relational Operators

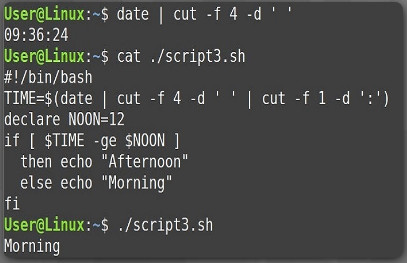

This figure is of a shell script determining if it is morning or afternoon.

In this script, the date command is cut until only the hour remains, and the result is placed in a variable. The if statement compares the variables $TIME and $NOON using the -ge operator to determine if the output is going to say “afternoon” or “morning”

If-Then Statements

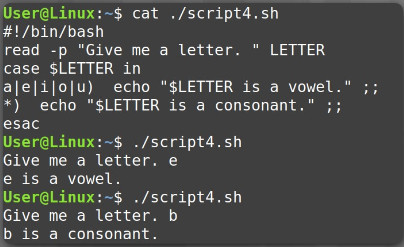

This figure is of a shell script determining if a vowel or consonant is used.

The case statement is able to lump various comparisons into categories. Note that the letter “b” is not mentioned in the script.

Case Statements

14.4.2.6 – Loops

In order to repeat commands or tasks a loop can be used. The three main types of loops found in scripts are the For loop, the While loop, and the Do-While loop.

The For loop repeats a section of code a specified number of times. The While loop checks a variable to verify that it is true (or false) before repeating a section of code. This is known as a pre-test loop. Finally, the Do-While loop repeats a section of code, then checks a variable to verify that it is true (or false). This is known a s a post-test loop.

Loops

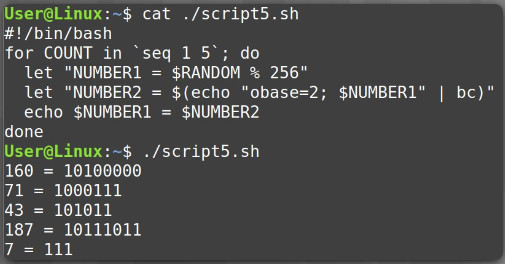

This figure is of a shell script which outputs five binary numbers.

The For loop in this script repeats a sequence exactly five times. The variable NUMBER1 is randomly generated to be between 0 and 255. The variable NUMBER2 is the binary conversion of NUMBER1. The spacing between the commands “for” and “done” are optional in some languages, but they help the programmer to understand what code is contained in the loop.

For Loops

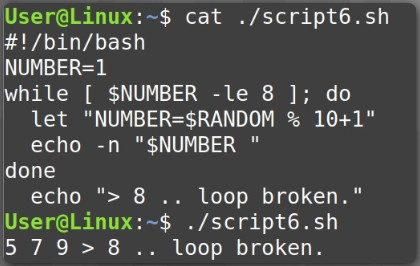

This figure is of a shell script which runs until a randomly chosen number is greater than 8.

In this script, the loop keeps running until a random number is chosen which is greater than eight. Notice how the variable NUMBER was set to 1 before the loop started. This was to prevent the test in the next line [ $NUMBER -le 8 ] from failing.

While Loops

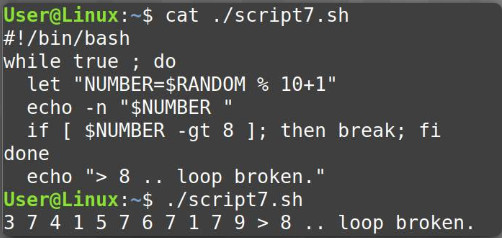

This figure is of a shell script determining if a vowel or consonant is used.

Unlike most compiled languages, several scripting languages lack a Do-While loop. In this case, we are emulating the post-test function using an If statement within the loop followed by a Break statement.

Do While Loops

14.4.2.7 – Lab – Write Basic Scripts in Windows and Linux

In this lab, you will write some basic scripts in different scripting languages to help understand how each language handles automating tasks

14.4.2.7 – Lab – Write Basic Scripts in Windows and Linux

14.5 – Summary

14.5.1 – Conclusion

14.5.1.1 – Chapter 14: The IT Professional

In this chapter, you learned about the relationship between communication skills and troubleshooting skills. These two skills need to be combined to make you a successful IT technician. You learned about the legal aspects and ethics of dealing with computer technology and the property of the customer.

You learned that you should always conduct yourself in a professional manner with your customers and co-workers. Professional behavior increases customer confidence and enhances your credibility. You learned how to recognize the signs of a difficult customer and learn what to do and what not to do when you are on a call with this customer.

You must understand and comply with your customer’s SLA. If the problem falls outside the parameters of the SLA, find positive ways of telling the customer what you can do to help, rather than what you cannot do. In addition to the SLA, you must follow the business policies of the company. These policies include how your company prioritizes calls, how and when to escalate a call to management, and when you can take breaks and lunch. You performed several labs on how to fix hardware, operating system, network, and security problems.

You learned about the ethical and legal aspects of working in computer technology. You should be aware of your company’s policies and practices. In addition, you might need to familiarize yourself with your local or country’s trademark and copyright laws. A software license is a contract that outlines the legal use, or redistribution, of that software. You learned about the many different types of software licenses including Personal, Enterprise, Open Source and Commercial.

Cyber laws explain the circumstances under which data (evidence) can be collected from computers, data storage devices, networks, and wireless communications. First response is the term used to describe the official procedures employed by those people who are qualified to collect evidence. You learned that even if you are not a system administrator or computer forensics expert, it is a good habit to create detailed documentation of all the work that you do. Being able to prove how evidence was collected and where it has been between the time of collection and its entry into the court proceeding is known as the chain of custody.

Finally, you learned about script files which are files written in scripting languages to automate processes and tasks on various operating systems. The script file can save the technician a lot of time, especially when the same tasks need to be performed on many different computers. You learned about scripting languages and some basic Windows and Linux script commands. You learned about variables which are designated places to store information within a computer, conditional statements, which are needed for scripts to make decisions, and loops, which repeat commands or tasks.

Learning about scripting is important and so is experience practicing writing scripts. In this chapter you performed a lab writing some very basic scripts in different scripting languages to help understand how each language handles automating tasks.